Why are there no gay footballers in the Premier League?

The times, they are incredibly slow at changing.

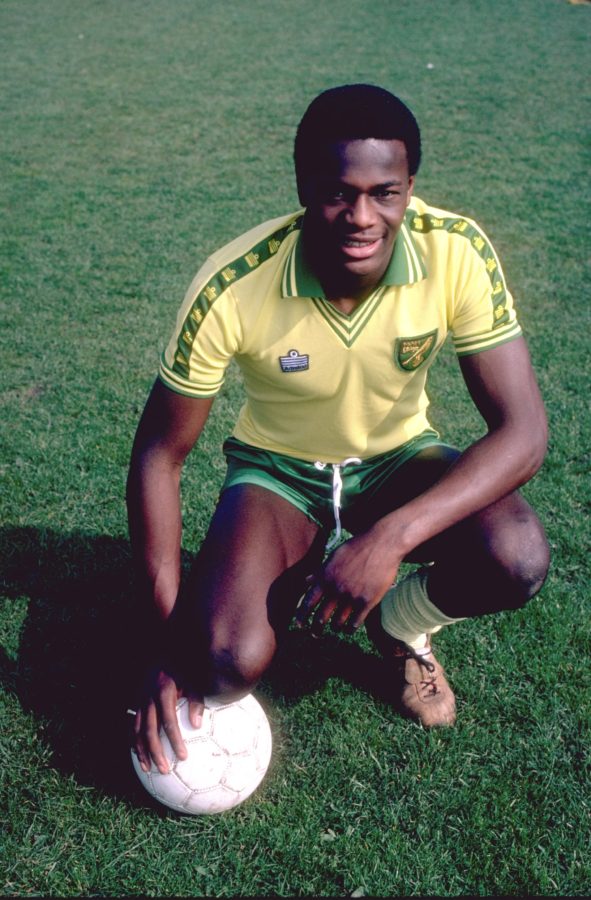

When Justin Fashanu came out as gay in 1990, it seemed that football would move with the times, and that the number of out players would inevitably grow as society matured.

Fashanu died from suicide in 1998, and 27 years after he came out, the Premier League has absolutely zero gay players – and never has done.

Despite the self-proclaimed best league in the world making some strides towards creating a better, more LGBT-friendly culture, discrimination is still a big issue in the game.

So, what progress has been made?

Well, we’ve seen the first ex-Premier League footballer come out, in the shape of former Aston Villa and Germany midfielder Thomas Hitzlsperger.

And LGBT supporters clubs are popping up all over the country, with most Premier League clubs now having one.

Former Leeds United player Robbie Rogers came out in 2013 after he had left Britain for the US, while Anton Hysen came out as gay in 2011, at the age of 20 – though that was in Sweden.

Closer to home, in women’s football, England stars Casey Stoney and Lianne Sanderson are among those who have come out and continued to play at the highest level.

We’ve even seen the first football Premier League club to partner with Stonewall, and several high-profile campaigns enthusiastically taken on by top teams, including the Rainbow Laces initiative.

And other sports like rugby and tennis have long had LGBT icons, such as Wales international Gareth Thomas and Martina Navratilova.

But still, no Premier League footballer has come out.

So – why not?

1. Fans

Back in 2013, the Brighton and Hove Supporters Club and the Gay Football Supporters’ Network (GFSN) compiled a dossier detailing abuse from other fans.

They found that in more than half of Brighton’s matches that season, their fans had been targeted with homophobic chants.

They ranged from “Does your boyfriend know you are here?” and “We can see you holding hands” to “Town full of faggots / you’re just a town full of faggots.”

Taking your child to a match or just trying to support your team in that kind of atmosphere – even surrounded by tens of thousands of your own fans – is incredibly difficult.

50 percent of football supporters have heard homophobic chanting at matches.

Imagine playing in front of millions while that kind of abuse rains down on you. Just you.

A BBC survey in October last year found that 82 percent of supporters would have no issue with a gay player – but eight percent of football fans said they would stop watching their team.

This small minority could easily make a player’s life hell if they came out as anything but straight.

Social media alone would likely be a nightmare.

Former England and Chelsea players John Terry, Ashley Cole and Graeme Le Saux have all been the targets of homophobic chants.

Back in 1999, England striker Robbie Fowler taunted Le Saux by waving his backside at him.

He received a two-match ban for the abuse – just after receiving a four-match ban for a harmless celebration in which he sniffed the goal-line as if it were cocaine.

Terry, who was banned for four matches in 2012 for racially abusing QPR defender Anton Ferdinand, was the subject of a chant last year which went: “John Terry’s queer, he takes it up the rear.

“He loves to sit on costas [sic] face “He takes it up the bum, he’s just a Chelsea scum”.

Sol Campbell, an England captain and Premier League champion at Arsenal, had to endure homophobic abuse for most of his career.

In 2009, a 42-year-old man and 14-year-old boy were found guilty of chanting “come on gay boy, that’s my gay boy” at Campbell during a match.

He told the BBC in 2014 that rumours about his sexual orientation started simply because he did not bring girlfriends along to matches.

And when he joined Arsenal in 2001, the abuse ramped up. “The FA allowed it,” Campbell said.

“When I needed it most no one said: ‘This is wrong’. We are young guys with very pressurised jobs, and they don’t help us.”

None of these players are gay, and yet they were still abused, simply because of some rumours.

Imagine coming out in that kind of environment.

2. Authorities

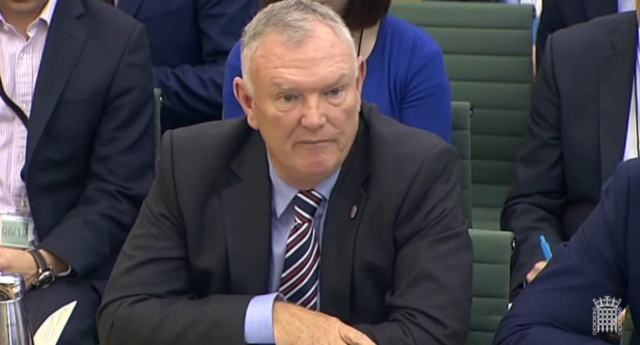

Greg Clarke, chairman of the Football Association, said today that the men’s game was “probably a couple of decades” behind women’s football.

And last year he said there would be “significant abuse” if a Premier League player came out.

Hardly the kind of welcome a player thinking of coming out would want.

Clarke admitted that he “would be amazed if we haven’t got gay players in the Premier League, and I am personally ashamed that they don’t feel safe to come out.”

And he seemed to dissuade anyone from doing so, saying: “I don’t think we’ve cracked the problem yet”.

“There’s a very small minority of people who hurl vile abuse at people who they perceive are different,” he added.

“If I was a gay man, why would I expose myself to that?” he asked.

He also told BBC Radio 5 Live last year that he hoped to provide a genuinely safe space for gay players in a “year or two”.

Which is great, except that despite it being 2017, the FA chairman is still telling gay players that it is not safe for them to come out.

(Photo by Jonathan Leibson/Getty Images for GLSEN)

3. Toxic masculinity

In 2013, not long after coming out, Robbie Rogers told the BBC that football was an amazing but brutal sport – one that “picks people up and slams them on their heads”.

“Adding the gay aspect doesn’t make a great cocktail,” he remarked.

The US international had just stepped away from the sport after coming out, and did return two months later – though not to England, where he had played until just before his announcement.

The pressure and spotlight of playing Premier League football in front of an estimated 1.5 billion people all over the world is intense enough without adding in a large dose of toxic masculinity.

The classic image of the British game is one in which hooliganism is rife, where the players are violent, the fans are belligerent and everyone is, above all, a ‘lad’.

The culture has changed somewhat – fans are generally less drunk and less likely to start throwing seats while at stadiums – but there are still lengths to go.

Offensive chanting, as we’ve seen, still exists, often under a thin veil of calling it ‘banter’.

And just watch the adverts during any televised football match.

Not only do they monolithically focus on cars, beer, betting and other stereotypically masculine pursuits, but they do so while excluding anyone who isn’t straight and male.

This contributes to the idea that football is not just solely for men; it’s for a certain kind of man, a stereotypical manly man, an über-lad who should be banished to the Stone Age where he belongs.

(OLIVER LANG/AFP/Getty Images)

4. A lack of role models

We’ve talked about Robbie Rogers, Thomas Hitzlsperger, Anton Hysen and Justin Fashanu, but they all either played too long ago or in too low a league to be role models for today’s players.

Footballers are part of society like anyone else, and Britain is increasingly accepting and celebrating LGBT people – but they’re young.

Tottenham Hotspur, who will finish second this season, have an average squad age that is under 26 years old.

And for the likes of top young stars like Dele Alli, Leroy Sané and Marcus Rashford, it’s hard enough being an instant celebrity without also coming out when you have no precedent.

The attention and pressure is already more than most would be able to cope with in a game where judgments on your performance and next contract can be decided by the smallest spin of a ball.

Imagine, on top of all of that, having to become a civil rights role model: the gay footballer who will influence more than a billion people in terms of how they view anyone who’s not straight.

Having to shoulder that responsibility, those hopes and expectations, while you try to succeed at the highest level in a 10-year career during which so many fall by the wayside is a lot to handle.

So far, it’s been too much.