Why doesn’t Northern Ireland have equal marriage yet?

Belfast Pride (Charles McQuillan/Getty Images)

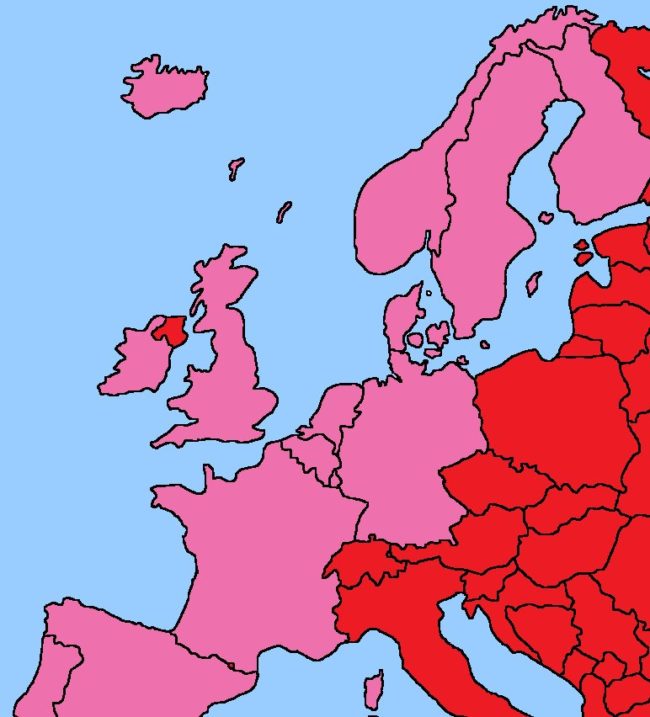

Northern Ireland is increasingly isolated in western Europe by banning same-sex marriage. What exactly is going on?

It has been four years since England and Wales approved equal marriage, and three years since Scotland followed suit.

Equal marriage has since spread across Western Europe – with France, Germany and Luxembourg also passing legislation in recent years to permit couples of the same sex to marry.

But in the UK, the 1.8 million people who live in Northern Ireland are still blocked from getting married to someone of the same sex.

So what’s going on?

A common misconception is that the region hasn’t passed equal marriage because not enough politicians support it.

But the truth is much more complicated than that.

A vote for equality

Back in 2015, a vote was held on an equal marriage bill in the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly (Stormont).

The bill narrowly passed through the chamber with 53 votes in favour and 51 against, winning a majority for the first time.

In most places that would have been that – the bill got a majority of votes, so it would become law.

However, thanks to Northern Ireland’s unique political system, that’s not what happened.

Petition of concern

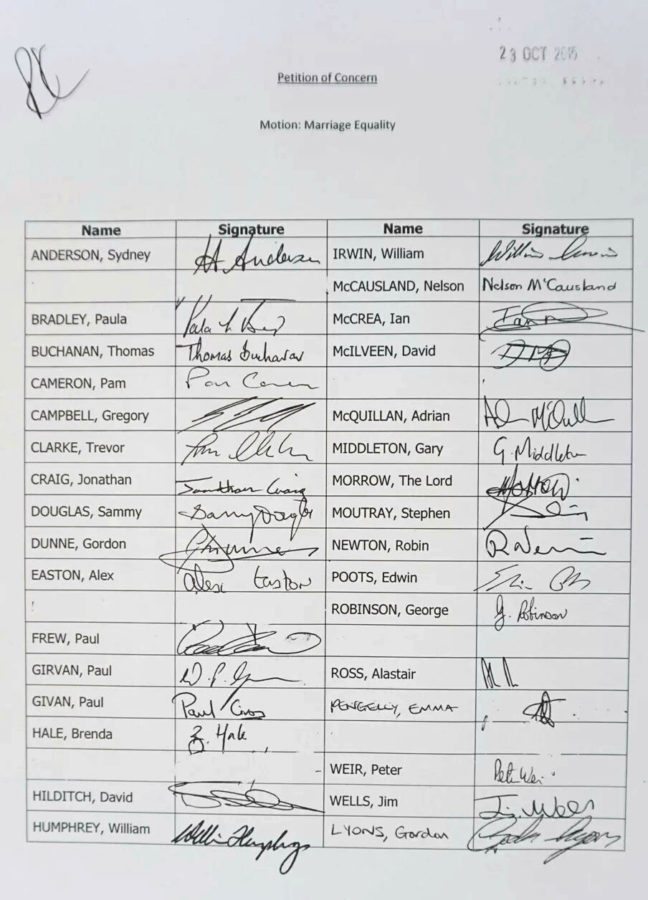

Faced with an equal marriage bill set to pass with majority support, the ultra-conservative Democratic Unionist Party used a peace process power known as a ‘petition of concern’ to override the Assembly.

The petition of concern power derives from the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which sought to establish power-sharing between mostly-Protestant unionists, who believe Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK, and mostly-Catholic republicans, who believe it should join a united Ireland.

Under the petition of concern procedure, factions that can amass the signatures of at least 30 Assembly Members are able to block bills indefinitely, unless they receive a super-majority.

The power was meant to ensure that contentious legislation can only be introduced with cross-community support, though its use in reality has seen it become more of a blunt political tool.

As the DUP was the largest unionist party in Stormont with 38 seats, its MLAs were easily able to file a petition of concern on marriage equality and block the bill.

Here’s a picture:

…And then all hell broke loose

Think you’ve got the slightly-infuriating stalemate down? Sadly, nothing is ever simple in Northern Ireland.

Progress on equal marriage moved even further from reality in January 2017, when the region’s largest republican party, Sinn Fein, withdrew from the power-sharing Executive that it had participated in alongside the DUP since 2011.

Sinn Fein had been incensed by a corruption scandal which implicated First Minister Arlene Foster, the leader of the DUP.

Ms Foster, who denies all wrong-doing, steadfastly refused to resign as DUP leader.

DUP leader Arlene Foster (Photo by Charles McQuillan/Getty Images)

Sinn Fein’s decision to withdraw from the Executive automatically led to the dissolution both of the Assembly and the Executive under the Good Friday Agreement.

Fresh Assembly elections were held, with the DUP and Sinn Fein once again coming out as the two largest parties, winning 28 and 27 seats in the new Assembly respectively.

However, that was more than six months ago, and the two parties locked in open-ended and unproductive negotiations on forming a new government ever since. Until they succeed the new Assembly cannot sit, and the Executive cannot change laws.

The pink and red lines

While there are many, many political and cultural bones of contention between DUP and Sinn Fein dating back generations, equal marriage has emerged as one of the key issues that has stalled talks on a fresh power-sharing deal that would see the Executive and Assembly come back online.

Sinn Fein, which strongly supports marriage equality, has set down a “red line” demand for any settlement to include the passage of an equal marriage bill. Meanwhile, the DUP has vowed to only sign a deal that would defend ‘traditional marriage’.

DUP official Jim Wells says that Sinn Fein’s demands for a concession on equal marriage will prevent a government being formed – warning that compromise will not be tolerated by the Democratic Unionists.

Jim Wells

He said: “Peter will not marry Paul in Northern Ireland. That’s an absolute no. Some of us would walk before that would happen. We feel very, very strongly about that.”

With the sides deadlocked on a whole string of issues, there’s no clear solution to the political crisis in sight.

This is bad news in general for Northern Ireland – but it also means no likely progress on equality in the foreseeable future.

Courts to the rescue?

In the absence of any political solution, LGBT activists pinned their hopes on two legal challenges, submitted to the High Court in Belfast.

One of the cases concerned couples seeking to enter into same-sex marriages in Northern Ireland, while another concerned couples who had entered same-sex marriages in England and were seeking recognition in Northern Ireland.

But in a blow to campaigners, Mr Justice O’Hara last month rejected both challenges, finding no grounds under human rights law to extend marriage rights or marriage recognition rights to same-sex couples.

He said: “It is not at all difficult to understand how gay men and lesbians who have suffered discrimination, rejection and exclusion feel so strongly about the maintenance in Northern Ireland of the barrier to same sex marriage.

“However, the judgment which I have to reach is not based on social policy but on the law.”

The decisions could be appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, but the weight of case law from previous challenges does not suggest a victory is at all likely.

So just as power-sharing is unlikely to come to the rescue, it’s pretty unlikely the courts will either.

Theresa May’s last chance saloon

The courts are out. Power-sharing is suspended. Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, there’s just one hope left for the foreseeable future – Theresa May.

Following the court ruling, LGBT activists now believe the only way to secure equal marriage in the region is for the UK government to directly intervene.

If no power-sharing agreement is reached, the responsibility for governing Northern Ireland will eventually revert to Westminster and the UK government, known as direct rule.

Under direct rule, it would be down to the current Conservative government to impose equal marriage.

The Director of The Rainbow Project John O’Doherty explained: “Of course, we would prefer that the Northern Ireland Assembly were in a position to grant these rights; the Assembly is not currently functioning.

“It is, therefore, the responsibility of Theresa May’s government to make the necessary amendments to the marriage legislation to make it applicable in Northern Ireland.

“The eyes of LGBT people around the world will now be on Theresa May. She says that she has changed her mind on LGBT equality over her years in Parliament. Now is her chance to prove it.”

Theresa May (Getty Images)

Clare Moore of Love Equality concurred: “During this period of political instability it is now imperative that the Westminster government takes immediate action to ensure that the rights of LGBT people in United Kingdom are available for all UK citizens.”

UK Prime Minister Theresa May recently expressed her personal support for same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland in a PinkNews column – but suggested that she did not plan to intervene.

Writing for PinkNews, Mrs May said: “I want all British citizens to enjoy the fullest freedoms and protections. That includes equal marriage – because marriage should be for everyone, regardless of their sexuality.

“And while that is a matter for the devolved government of Northern Ireland, I will continue to make my position clear – that LGBT+ people in Northern Ireland should have the same rights as people across the rest of the UK.”

A complicating factor is that the UK government is itself currently reliant on the DUP to continue functioning in Westminster under a confidence-and-supply deal, after failing to win a majority.

Any move to unilaterally impose equal marriage on Northern Ireland over the heads of the DUP could be a potentially-catastrophic gamble for Mrs May, who is already in a perilous position.

Responding to the prospect, a DUP spokesperson insisted: “Such legislation is a devolved matter and is for the Northern Ireland Assembly to decide upon. We want to see the Assembly and Executive restored as soon as possible.”

Why do the DUP care so much?

The UK’s Conservative Party has undergone a drastic evolution on LGBT rights in the past 20 years, from the party that pushed Section 28 and opposed an equal age of consent to one that secured equal marriage in England and Wales, and elected the most openly LGB Parliamentarians of any party in Europe.

But such an evolution is unlikely to happen in the DUP, for whom anti-LGBT beliefs are much more deeply ingrained.

The party itself was founded by ‘Save Ulster From Sodomy’ leader Rev. Ian Paisley, and his fundamentalist movement, the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster, still holds a strong ideological grip over the DUP.

The DUP aren’t just opposed to same-sex marriage on a policy basis – it is antithetical to the party’s view of basic morality.

Ian Paisley Jr, one of the party’s ten MPs, has spoken of his “hatred” of homosexuality, saying: “I am pretty repulsed by gay and lesbianism. I think it is wrong. I think that those people harm themselves and – without caring about it – harm society.”

Another MP, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, heads the Keep Marriage Special campaign which lobbied aggressively against equal marriage.

Many of the DUP’s most influential figures are diehard opponents of LGBT rights, and it’s hard to see any shift to a more passive stance win approval.

What if power-sharing is restored?

Though it seems unlikely at present, it is possible that a deal may yet be struck that sees power-sharing resume in Northern Ireland.

If it does, power will be restored to an Assembly markedly different than that during the previous term.

Following the election earlier this year, there would be a stronger majority for equal marriage in the new chamber, though this would still not be veto-proof if facing a petition of concern.

The DUP now have 28 seats in the Assembly, short of the 30 needed to outright veto the issue.

However, they are likely to call in help from other unionists who are just as strongly opposed to equal marriage.

Unionists from two other parties, the Ulster Unionist Party and Traditional Unionist Voice, have vowed to prop up the DUP on the issue.

East Antrim MLA Roy Beggs of the UUP has said he would join a veto effort, while Jim Allister of TUV is also a fierce opponent of LGBT rights who would likely aid the DUP.

But even if the Assembly returns, there’s no guarantee that it will be under the same rulebook as before.

As the number of seats on the Assembly has reduced overall, the threshold for a Petition of Concern could be decreased, handing a boost to the DUP and negating the need for them to rely on fringe parties.

There are some calls to reform the petition of concern procedure to make it less open to abuse. However, the DUP are unlikely to assent to any deal that reduces their influence without putting new safeguards in place.

Assuming the petition of concern continues in its current form and the DUP can cobble together a coalition of 30 MLAs, LGBT activists would be right back where they were two years ago – with an Assembly that supports same-sex marriage, beholden to a powerful faction that will never allow it.

The sad reality for LGBT people in Northern Ireland is that progress is unlikely to come any time soon, no matter what happens next politically.