New biography paints a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci’s life as an openly gay man

A new biography explores Leonardo da Vinci’s life as an openly gay man in 15th century Florence.

Walter Isaacson’s work, Leonardo da Vinci: The Biography, is based on thousands of pages of the artist’s own notebooks and new discoveries about his life and work.

Though his sexuality has been an open secret for some time, many do not know the extent to which da Vinci lived his life as a gay man.

The book cites the painter’s string of younger male companions, the depiction of male sexuality in his art, and accusations of sodomy made against him during his lifetime.

In fact, the artist was twice publicly accused of having gay sex, his youthful male protege was removed because of the “wicked life he had led” with Leonardo, and his own writings repeatedly muse on his own attraction to men – and borderline revulsion to sex with women.

Isaacson casts the author as “a bit of a misfit: illegitimate, gay, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted and at times heretical”.

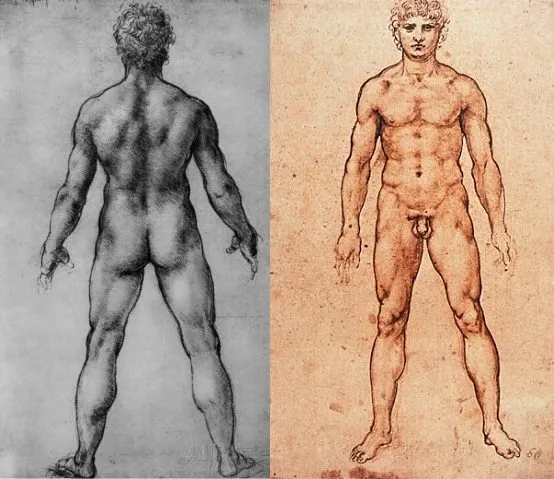

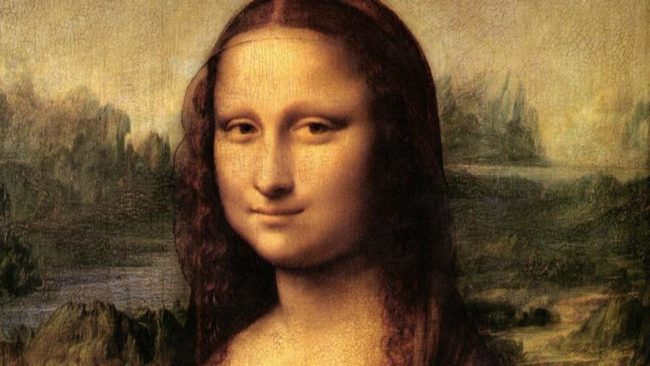

Leonardo’s female portraits were largely asexual, in contrast to his often erotic drawings of men

The book challenges previous assertions in art history – mostly from before the mainstream acceptance of gay people – that Leonardo lived a celibate life.

Isaacson wrote: “There is no reason to believe that he remained celibate… on the contrary, in his life and in his notebooks, there is much evidence that he was not ashamed of his sexual desires. Instead he seemed amused by them.

The author added: “In his drawings and sketches, he showed a far greater fascination for the male body than the female. His drawings of male nudes tend to be works of tender beauty, many rendered in full length.

“By contrast, almost all of women he painted, with the exception of a now lost Leda and the Swan, are clothed and shown from the waist up.”

Leonardo’s female portraits were largely asexual, in contrast to his often erotic portrays of men

The book also challenges suggestions that the artist was ashamed of or hid his lifestyle.

Isaacson wrote: “Leonardo was romantically and sexually attracted to men and, unlike Michelangelo, seemed to be just fine with that.

“He made no effort either to hide or proclaim it, but it probably contributed to his sense of being unconventional, someone who wasn’t geared to be part of a family procession of notaries.

“Over the years, he would have many beautiful young men as part of his studio and household.

“Two years after [facing public accusations of sodomy], on a page with one of his many notebook doodles of an older man and a beautiful boy facing each other in profile, he wrote, ‘Fioravante di Domenico of Florence is my most beloved friend, as though he were my …’

“The sentence is unfinished, but it leaves the impression that Leonardo had found an emotionally satisfying companion.

“Shortly after this note, the ruler of Bologna wrote to Lorenzo de’ Medici about another young man, who had worked with Leonardo and even adopted his name, Paulo de Leonardo de Vinci da Firenze.

“Paulo had been sent away from Florence because of the ‘wicked life he had led there’.”

Circa 1510, Florentine High Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, engineer and scientist, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519). (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It adds: “Leonardo’s most serious longtime companion, who joined Leonardo’s household in 1490, was angelic looking but devilish in personality, and thus acquired the nickname Salai, the Little Devil.

“Vasari described him as ‘a graceful and beautiful youth with fine curly hair in which Leonardo greatly delighted’, and he was the subject of many, sexual comments and innuendos, as we shall see.’

“Leonardo was never known to have had a relationship with a woman, and he occasionally recorded his distaste for the idea of heterosexual copulation.

“He wrote in one of his notebooks, ‘The sexual act of coitus and the body parts employed for it are so repulsive that, if it were not for the beauty of the faces and the adornment of the actors and the pent-up impulse, nature would lose the human species.’

“Homosexuality was not uncommon in the artistic community of Florence.

“Verrocchio never married, nor did Botticelli, who was also charged with sodomy. Other artists who were gay included Donatello, Michelangelo, and Benvenuto Cellini (who was twice convicted of sodomy).

“Indeed, l’amore masculino, as Lomazzo quoted Leonardo calling it, was so common in Florence that the word Florenzer became slang in Germany for ‘gay’.

“When Leonardo worked for Verrocchio, a cult of Plato was arising among some Renaissance humanists, and it included an idealized view of erotic love for beautiful boys.

“Homosexual love was celebrated in both uplifting poems and bawdy songs.

“Nevertheless, sodomy was a crime, as Leonardo became painfully aware, and it was sometimes prosecuted. During the seventy years following the creation of the Officers of the Night in 1432, an average of four hundred men per year were accused of sodomy, and about sixty per year were convicted and sentenced to prison, exile, or even death.”

Circa 1500, Italian painter, sculptor, architect and engineer Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519). Original Artwork: Self portrait. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The book also delves into allegations of sodomy levelled in public against a young da Vinci.

Isaacson wrote: “In April 1476, a week before his twenty-fourth birthday, Leonardo, was accused of engaging in sodomy with a male prostitute. It happened around the time that his father finally had another child, a legitimate son who would become his heir.

“The anonymous allegations against Leonardo was placed in a tamburo, one of the letter drums designated for receipt of morals charges, and involved a seventeen-year-old named Jacopo Saltarelli, who worked in a nearby goldsmith shop.

“He ‘dresses in black’, the accuser wrote of Saltarelli, ‘is party to many wretched affairs, and consents to please those persons who request such wickedness of him’.

“Four young men were accused of engaging his sexual services, among them Leonardo di Ser Piero da Vinci, who lives with Andrea de Verrocchio.

“The Officers of the Night, who policed such charges, launched an investigation and may have imprisoned Leonardo and the others for a day or so. The charges could have led to serious criminal penalties if any witnesses were willing to come forward.

“Fortunately, one of the other four young men was a member of a prominent family that had married into the Medici clan. The case was dismissed ‘with the condition that no further accusations are made.’

It adds: “A few weeks later, a new accusation was made, this one written in Latin.

“It said that four had engaged in multiple sexual engagements with Saltarelli. the Because it too was an anonymous allegation and no witnesses came forth to corroborate it, the charges were once again set aside with the same conditions. That, apparently, was the end of the matter.

“Thirty years later, Leonardo wrote a bitter comment in a note-book: ‘When I made a Christ-child you put me in prison, and now if I show him grown up you will do worse to me.’

“The comment is cryptic. Perhaps Saltarelli had modelled for one of his depictions of a young Jesus.”

Of the artist’s sexuality, Isaacson added: “On a deeper level, Leonardo’s homosexuality seems to have been manifest in his sense of himself as somewhat different, an outsider who didn’t quite fit in. By the time he was thirty, his increasingly successful father was an establishment insider and a legal adviser to the Medici, the top guilds, and churches.

“He was also an exemplar of traditional masculinity; by then he’d had at least one mistress, three wives, and five children. Leonardo, on the contrary, was essentially an outsider.

“The birth of his stepsiblings reinforced the fact that he was not considered legitimate. As a gay, illegitimate artist twice accused of sodomy, he knew what it was like to be regarded, and to regard your-self, as different. But as with many artists, that turned out to be more an asset than a hindrance.”

A film based on the book’s account of Leonardo’s life is in development at Paramount, with Leonardo DiCaprio signed on to play the lead, in a fortunate turn of nominative determinism.