Opinion: Chicago is a story about women. So why is Cuba Gooding Jr the face of the production?

Even if you’re not a London dweller, it’s pretty hard to miss the stripline of advertisements that line the tube’s escalators, offering the city’s most supposedly tantalising tourist attractions.

Whether it’s fine dining experiences, spa trips or theatre productions, lots of these offerings are designed to be beguiling to the eye and most probably heavy on the purse – so they tend to rely on their biggest selling point in order to make the grade.

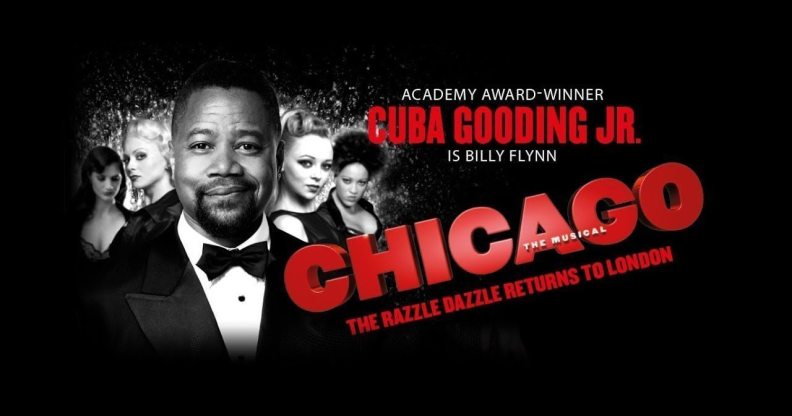

That’s perhaps why some people like me might have been somewhat perplexed to find that Cuba Gooding Jr – and only Cuba Gooding Jr – has been celebrated as the main feature of the latest West End iteration of Chicago.

Chicago, a story created in 1926 to elucidate the revolutionary force and power of women in the wake of sexual repression and violence, features Roxie Hart and Velma Kelly at the centre of its narrative – two women who are attempting to get off the hook for murders that they have indeed committed.

(Rehearsals of Chicago The Musical, Tristram Kenton)

Meditating on the power struggle between the genders that blisters into bloodspill, the narrative eviscerates the resurgent force of women – and the revolutionary potential of those who wish to rise up in a world where they are categorised as either housewives or eye candy.

Yet in spite of the feminist narrative, and the fact that the show is nearly an all-female cast Cuba Gooding Jr has been selected as the face to tell this story – and not one woman out of the leading cast has been deemed worthy enough to fight his grace.

Although Cuba Gooding Jr’s role as slippery lawyer Billy Flynn is an identifiable role in the musical, he operates as an assistant who lubricates Roxy and Velma’s motions in the production – and may be the leading male role, but not the leading role in the production.

Although the West End giving into the faces of some of its shinier stars is nothing new, it seems rather tone-deaf that the production team that are selling Chicago didn’t want to sell a story about women with the face of one of their many women.

(Rehearsals of Chicago The Musical, Tristram Kenton)

And in a show like Chicago, omitting the purpose of women in the heady search for fame is quite a tone-deaf discrediting of its own narrative.

Let’s hope that less shows rely on the security of a male presence to bolster its sales – and understand that when advertising shows like Chicago, it’s nothing short of essential to let women do the talking.

It is galling that a show that thrives on female empowerment has fallen victim to the sort of passive sexism that is swept under the carpet throughout the story itself.

If anything, the show has taught the stars and audience alike that in order for women to be taken more seriously, they need to be celebrated as legitimate luminaries in the creative process – and should be given credit when it is undoubtedly required.

Yet Chicago, a musical created to demonstrate the startling lack of career goals and options available to women, has paled into that stereotype with the way it has sold itself – and risks rendering the production an archaic reiteration that is fixed in the gender stereotyping that was indeed prevalent in 1926.