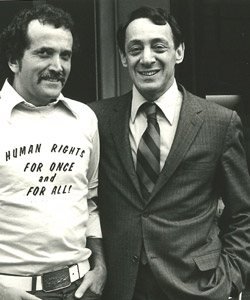

Who was Harvey Milk? Meet California’s first openly gay elected official

Harvey Milk is the ultimate 20th century LGBT+ icon: he is the subject of books, films, postage stamps, plaques, a national holiday and is even the namesake of an airport terminal.

But Milk isn’t just a symbol: as the United States’ first openly gay politician, and an inspirational orator, his life and work helped improve people’s lives in a very real way.

He ignited and pioneered the LGBT rights movement in San Francisco – and the whole nation of America – leaving behind a critically important legacy when his life was cut short in 1978.

Harvey Milk was just 48 years old when he was shot dead by a former colleague, and he’d only served 11 months in his position on San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors where he bravely sought to bring about change for LGBT+ people.

Despite the short tenure, his activity and activism left its mark on society.

Writing in 2014 in The Huffington Post, former US ambassador Nancy Brinker said: “Harvey Milk did something that few people ever do – he started a movement that changed the nation.”

It was a movement he didn’t begin until later in life, though. Born in Woodmere, New York, in 1930, Milk (described as a “man’s man” at college) first worked as a teacher, served in the Navy, and worked on Wall Street before rejecting his conservative (and closeted) professional life.

Milk moved to the Castro district of San Francisco in 1972 to begin another life.

There he opened a camera shop called Castro Camera with boyfriend Scott Smith, and it was here that he began to strike out against the injustices he saw around him – related to both the LGBT+ community and wider society.

Milk was shocked when a teacher came into his store to borrow a projector because the equipment in the schools did not function, was enraged by the Watergate scandal hearings on television, and had run-ins with city officials.

Angered further about the way San Francisco was seemingly controlled by real estate moguls and corporations, Milk decided it was time to run for city supervisor.

He said later of this period of his life: “I finally reached the point where I knew I had to become involved or shut up.”

In 1973, Milk ran his first campaign on a progressive, liberal platform – arguing against government interference in private sexual matters and for the legalisation of marijuana – but was not backed by most of the city’s gay establishment.

While he lost this campaign, Milk had enjoyed his first taste in the public eye. It was around this time that he began to style himself “The Mayor of Castro Street”.

He became heavily involved with organising in the local community, helping the Teamsters union with their Coors boycott, for example

The Teamsters labour union (representing a huge number of truck drivers) wanted to put pressure on Coors for refusing to sign their union contract.

Straight union organisers asked Milk for assistance with gay bars – he could persuade Castro district bars to stop stocking Coors.

In return, Milk asked the union to hire more gay drivers – if LGBT people were to support the boycott, the Teamsters would have to allow openly gay people in.

Milk started working on his end of the bargain, but other LGBT+ activists were infuriated when they learnt that Coors’ male job applicants were forced to take lie detector tests asking whether they were homosexual – they joined union activists to support the strike, going from bar to bar pinning badges on drinkers and bartenders.

The Coors boycott took off in San Francisco, and spread nationally. In California, the market share of Coors dropped from 40% to 14%.

Facing this boycott, the business stopped asking job applicants about their sexuality and signed a new contract with the Teamsters.

The Teamsters union also upheld its promise and gay men began driving for numerous beer companies.

The same year, two gay men were prevented from opening an antiques store, when the Eureka Valley Merchants Association (EVMA) refused them a business license.

In response, Milk and other gay business owners founded the Castro Village Association – with Milk as the president – and organised the highly successful Castro Street Fair in 1974.

It was all about collectivism and activism, organising at the grassroots level to enable the community to take for themselves – business opportunities, equal rights – what the mainstream establishment refused to allow.

After one other failed attempt at election – while gaining an increasingly high profile, founding the San Francisco Gay Democratic Club, and talking about topics ranging from LGBT rights to childcare and free public transport – Milk finally won a seat on the San Francisco City-County Board in 1978.

His swearing in gained national attention, as the first openly gay man in the United States to win an election for public office.

Milk served almost eleven months in office and was instrumental in historic victories including defeating anti-gay legislation known as the Briggs Initiative, or Proposition 6 which would have barred gay people from teaching in schools.

The Briggs Initiative was defeated by over one million votes on in November 1978, with the support of high profile national figures like Ronald Reagan and then President Jimmy Carter.

Milk persuaded the city council to pass a Gay Rights Ordinance in 1978 that protected gay employees from being fired from their jobs.

Tavaana – an Iranian e-learning institute, set up to allow academic discussion of subjects forbidden by the Iranian government – sums up Milk’s ambitions for his time in office like this:

“For Milk, winning the election, while monumental, was just the first step in his plan to promote gay rights and equality.

“Milk sought not only to change the stereotypes that existed about gays, but to also promote a legal framework that supports gays, including the passage of a gay rights bill, and speaking out against a barrage of legislation, which would restrict gays’ civil and political liberties.”

One of Milk’s core messages was the importance of visibility. In his famous ‘Hope Speech’ given at San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Day parade in 1978, he emphasised how transformative this visibility could be:

“You must come out. Come out… to your parents… I know that it is hard and will hurt them but think about how they will hurt you in the voting booth! Come out to your relatives… come out to your friends… if indeed they are your friends.

“Come out to your neighbours… to your fellow workers… to the people who work where you eat and shop… come out only to the people you know, and who know you. Not to anyone else. But once and for all, break down the myths, destroy the lies and distortions.”

Untimely death

On November 27 1978, a former colleague who’d recently been refused his job back, and who’d expressed homophobic, anti-liberal views in the past – Dan White – entered City Hall with a loaded revolver, and shot the mayor dead.

He then turned his weapon on Harvey Milk, killing him too.

President Jimmy Carter said later that day: “I know I speak on behalf of the Nation when I express a sense of outrage and sadness at the senseless killings today of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk (…)

“Supervisor Milk was a hard-working and dedicated supervisor, a leader of San Francisco’s gay community who kept his promise to represent all his constituents. Rosalynn and I express our deepest sympathies to the families and friends of both men.”

Following the news, the LGBT community of San Francisco came out in droves to mourn and celebrate Milk’s life.

Tens of thousands attended a candlelight march in Castro. They would later take to the streets when killer Dan Wood was given a widely-perceived lenient jail sentence, in the now infamous White Night Riots.

Milk was cremated and his ashes spread across the Pacific Ocean.

A plaque in front of 575 Castro Street says: “Harvey Milk’s hard work and accomplishments on behalf of all San Franciscans earned him widespread respect and support. His life is an inspiration to all people committed to equal opportunity and an end to bigotry.”

Sean Penn plays Harvey Milk in “Milk” (Photo by Focus Features)

This inspiration has led to numerous posthumous accolades and marks of remembrance.

Milk’s life has been the subject of stage productions, books, and an Academy Award winning film – ‘Milk’, starring Sean Penn.

The movie used extras who had been present at the actual events for large crowd scenes, including a scene depicting Milk’s Gay Freedom Day Parade speech.

He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama in 2009 and in 2014, the US post office unveiled a range of stamps to honour and thank Milk for his help in “liberating gay couples.”

In March 2018 it was announced that a terminal at San Francisco International Airport (SFO) will be renamed in Milk’s honour.

Harvey Milk’s continuing visibility in American life speaks to one of his most repeated expressions: “You gotta give ‘em hope!”