Who was Magnus Hirschfield? Meet the doctor and LGBT+ activist who became a Nazi target

L0024860 World League for Sexual Reform conference.

Magnus Hirschfield was a ground-breaking physician, sexologist and activist, researching and writing about LGBT+ issues at a time when it could put him in serious danger.

Homosexuality was illegal in both East and West Germany until the late 1960s. Yet as at the turn of the 20th century, Hirschfield – who was gay himself – was working on gathering statistical information about “Homosexualität und Bisexualität.”

He also looked into issues still pressing today.

Dubbed the “Einstein of sex,” Hirschfield recorded the effects of hate and violence against lesbians and homosexual men and other groups of people, and conducted the first statistical surveys of lesbian and homosexual suicide.

Self harm and suicide among the LGBTQ+ community is something society is still getting to grips with now, a century on: according to research, LGBTQ+ teens and young adults can be up to four to seven times more likely to self-harm or contemplate suicide compared to their straight peers.

John D’Emilio, co-author of ‘Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America,’ describes Hirschfield and his legacy this way:

“Magnus Hirschfeld is one of the forgotten giants of history. He can rightly be considered the founder of the first gay liberation movement, more than a century ago.

“The target of vicious anti-Semitism and homophobia, he was brave enough to stand his ground and keep fighting for justice.”

Born in Poland in 1868, the Jewish Hirschfield studied philosophy, philology and medicine in various German cities.

He then spent time in the US, and during his stay in Chicago immersed himself in the city’s underground gay community.

Magnus Hirschfeld and his partner, Karl Giese

“Justice through science”

Back in Germany and working as a physician, in 1896 Hirschfield issued a pamphlet (under a pseudonym) on homosexual love, called ‘Sappho and Socrates’.

The following year he founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee with the publisher Max Spohr, the lawyer Eduard Oberg, and the writer Franz Joseph von Bülow.

Described as the “1890s equivalent of UK gay lobby group Stonewall”, the Committee aimed to research and defend the rights of gay people and to repeal German laws criminalising homosexuality.

They argued that the law encouraged blackmail. The group’s motto – “Justice through science”, reflected Hirschfeld’s belief that a better scientific understanding of homosexuality would eliminate social hostility toward homosexuals.

Hirschfield noticed that many of his gay patients were committing suicide and/or presented with “Suizidialnarben” (scars left by suicide attempts), and often found himself trying to give his patients a reason to live.

He began researching homosexuality, and distributed surveys to people – predominantly men – asking about their sexual preferences.

These were sent to more than 5,700 German metalworkers and 3,000 male students in Berlin, among others.

From this research, Hirschfeld estimated that three out of every 100 gay people committed suicide every year.

On top of this, a quarter had attempted suicide at some point in their lives and that the other three-quarters had had suicidal thoughts at some point.

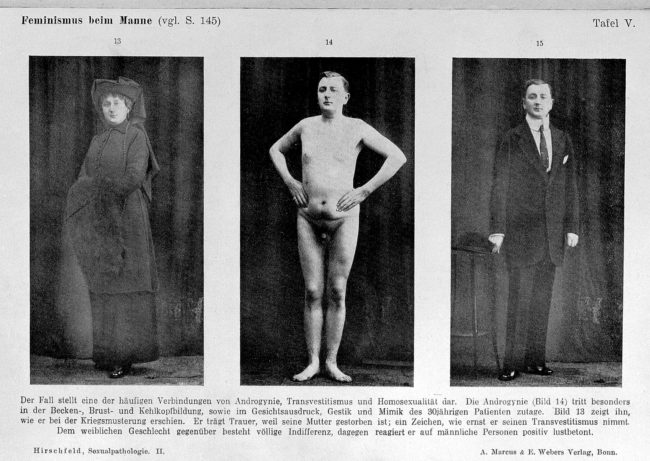

Hirschfeld was an early researcher of trans issues (Creative Commons)

Under Hirschfeld’s leadership, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee gathered over 5,000 signatures from prominent Germans – including Albert Einstein and Hermann Hesse – on a petition to overturn laws criminalising homosexuality.

The committee used his research to argue that, under current social conditions in Germany, life was literally unbearable for homosexuals.

Hirschfield also researched sexuality in other cultures, and in 1914 published ‘Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes’ (The Homosexuality of Men & Women).

The book sought to comprehensively prove that homosexuality occurred in every culture.

Hirschfield and feminism

In 1905, Hirschfeld joined the Bund für Mutterschutz (League for the Protection of Mothers), the feminist organisation founded by Helene Stöcker, a German feminist, pacifist and gender activist.

He campaigned for the decriminalisation of abortion, and against policies that banned female teachers and civil servants from marrying or having children.

Both Hirschfeld and Stöcker believed that there was a close connection between the causes of LGBTQ+ rights and women’s rights.

Ancient dildo box from Japan, remnant from the Institute of Sexual Research, on display at the Jewish Museum, Berlin

Institute of Sexual Research

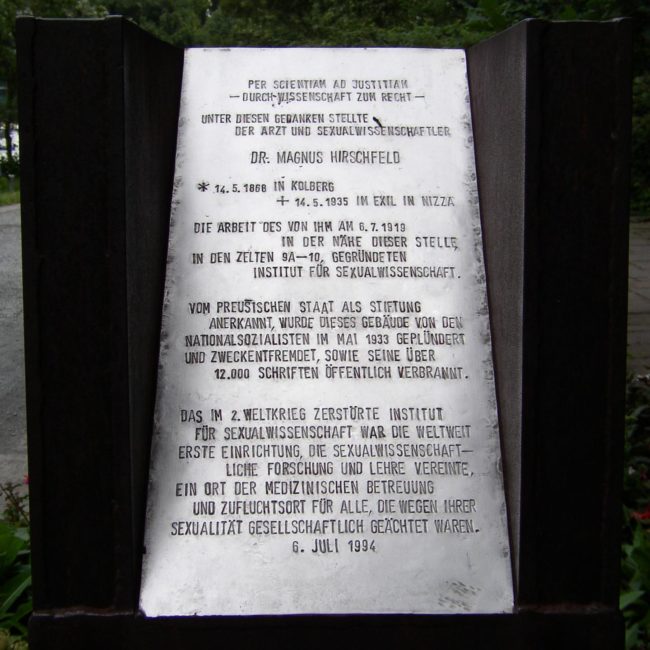

In 1919 – under the more liberal atmosphere of the newly founded Weimar Republic after World War I – Hirschfeld founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute of Sexual Research).

The Institute, in a building near the Reichstag, housed his immense archives and library on sexuality and provided educational services and medical consultations.

The Institute also featured the Museum of Sex, an educational resource for the public, which is reported to have been visited by school classes.

It operated as a refuge for homosexual and transgender people, a place where social as well as medical support could be found.

Hirschfeld himself lived at the Institution with his lover, Karl Giese. They were a well-known couple in the gay scene in Berlin, and as Hirschfeld liked to cross-dress, he was known as “Tante Magnesia” (Auntie Magnesia).

People from all over Europe and beyond were drawn to the Institute, including Christopher Isherwood and W. H. Auden, as well as many novelists, playwrights, artists and poets.

When the Nazis took power, however, the safe haven that the Institute had created was brought to an end.

German students and Nazi SA plunder the library of the Institute for Sexual Research

On 6 May in 1933, members of the National Socialist Student League stormed the building, beat up the staff and smashed up the premises.

That afternoon the Institution’s books were removed and burned, and in the evening officials arrived to announce its doors would be closed forever.

At this time, Hirschfield was on a speaking tour elsewhere in Europe. He never returned to Germany, and ended his years writing about his experience as a global sexologist. Hirschfield died in France in 1935.

Modern context

Despite being ahead of his time in many ways, some of Hirschfield’s theories do not stand up today.

LGBTQ+ rights campaigner Peter Tatchell writes: “Far in advance of others, he concluded everyone is a mixture of male and female.

“But this perceptive true analysis led him to erroneously advance the idea that lesbian and gay people were an ‘intermediate sex’ that was biologically predetermined at birth. In his view, male homosexuals possessed a ‘woman’s soul trapped in a man’s body’.”

“This well-intentioned misjudgement aside, Hirschfeld was right on most other things. He can and should be forgiven.”

Memorial plaque for Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin (Creative Commons)

Award-winning gender studies academic Dr Ina Linge similarly acknowledges Hirschfield’s flaws and argues that they should not discount him from modern conversations around sexuality and gender.

“He also believed that homosexuality was inborn. As such, it was considered a physical affliction that could be diagnosed by looking at the homosexual body.

“He argued that homosexuality had physical markers – such as wider hips – and that one day it would be possible “to diagnose the Uranian [member of a third sex] as soon as he enters the world,” Linge explains.

“Of course, we would not accept this explanation today. But we shouldn’t forget that Hirschfeld, himself gay and an occasional cross-dresser, stood up for sexual equality and the elimination of anti-homosexual laws.

“To be able to ‘diagnose’ homosexuality meant that it could then be considered as a natural, and thus ‘normal’, variation of the sexual spectrum – and most importantly, no longer a crime.”

These out-dated ideas aside, Hirschfield remains celebrated by many in the LGBTQ+ community.

In 2014 on the 75th anniversary of his death, the Mémorial de la Déportation Homosexuelle (MDH), in partnership with the new LGBT Community Center of Nice organised a formal delegation to the cemetery where he is buried.

Speakers recalled Hirschfeld’s life and work and laid a large bouquet of pink flowers on his tomb, addressing him as “the pioneer of our causes”.

The slab covering the tomb is engraved with the motto he lived his life by: “Through science to justice.”