A kinder Grindr is too late. The damage to gay minorities’ self-esteem is done.

“It’s time to play nice.”

That’s the tagline for Grindr’s new campaign, Kindr, which, the dating app says, is a concerted effort to stamp out sexual racism and discrimination on its platform. But Grindr’s campaign to “play nice” is as useful as scoring a touchdown after the final whistle.

I do not believe that the sexual racism ingrained on Grindr can be eradicated—no matter how kind Grindr implores its users to be.

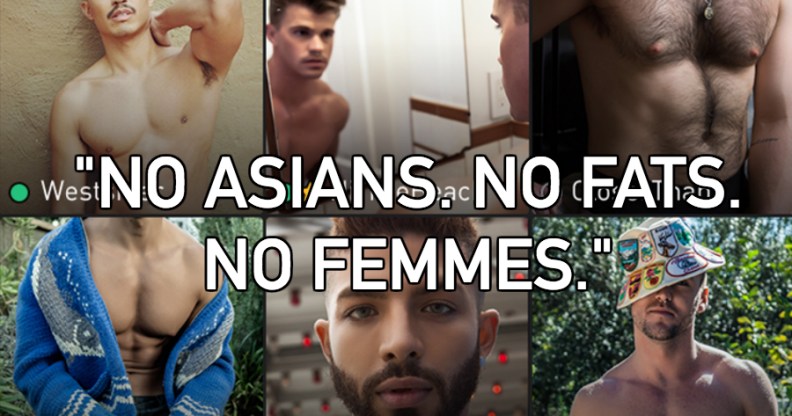

Grindr’s new guidelines say it will ban people who openly discriminate against others in their bios, which might stop people from writing “No Asians, no femmes,” but here’s the problem: The toxicity that Grindr has hosted to date has shaped the way an entire generation of trigger-fingered, horny men feel it is okay to speak to others. That, in turn, has shaped the parlance for gay dating across the whole internet—not just on Grindr. And that has shaped how minorities within the gay community are left feeling inferior.

For many ethnic minorities around the world, myself included, Kindr cannot undo the indignity of years of both the explicit and tacit racism we have endured, the side effects of which have left an indelible mark on our psyche.

Navigating the horny, and often high, shark-infested waters of Grindr has affected my self-esteem and sense of self worth more than any face-to-face rejection in a gay club.

As a queer brown man, I knew dating in a white predominant country like Britain wasn’t going to be easy: There are more white people than there are minorities. But having been born and raised in multicultural London—where I grew up with friends of all different skin colours—it seemed truly implausible that the segregation that persists on gay dating apps could exist.

I’ve seen the famous “No Asians” verbiage in people’s bios, been ignored, or told I’m “good looking… for an Asian guy” but ultimately the wrong “type”—which, as I’ve written before, is usually codified speak for “wrong skin colour”—and I’ve even been verbally abused as an “ugly paki.”

Grindr conversation (Grindr)

Think what it would feel to have those words hurled at you in the street. Yet people are emboldened to say things they wouldn’t otherwise say through the protection of their screen.

This degradation, for me, has served only to amplify my insecurities about my skin colour, my body and sex appeal: “Am I ugly?” and “What is wrong with me?” are two common questions that creep into my thoughts, although I’m subconsciously aware that I shouldn’t feel this way.

More dangerously, seeing the white, musclebound jocks that dominate the array of profile pictures, convinced that they are more conventionally attractive and having way more sex, I have questioned my own identity. “Why can’t I look like that?” I’ve asked myself. “Why do I have to look like me?”

To feel such discomfort in my own skin, of my heritage, feels like a painful betrayal of the incredibly rich roots that my immigrant mother and father have bestowed me with. I am proud to be their son and I am proud to be brown. Yet part of me longs for the acceptance—and frequent sex—that comes with being an attractive white gay man on Grindr.

No Kindr policy can change that.