This is what it was like to live through the AIDS crisis

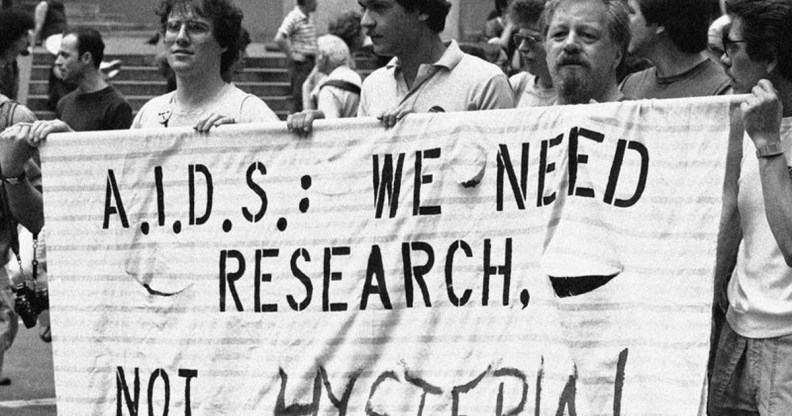

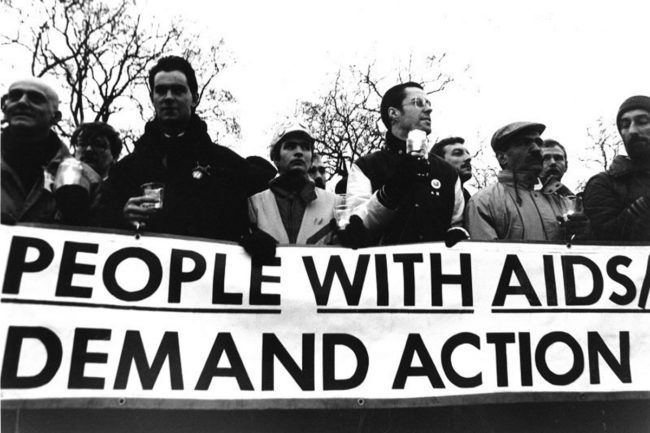

Tens of thousands died during the crisis, and tens of millions have died worldwide (Rollis University/New York Historical Society

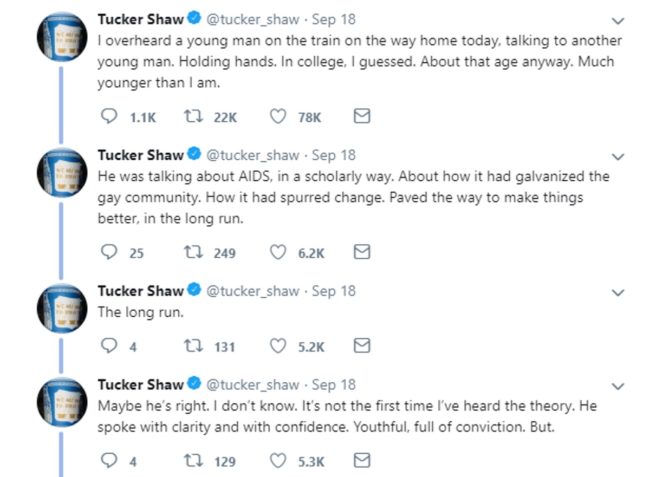

A Twitter thread about the heartbreak of living through the AIDS crisis has gone viral, with many people reacting emotionally to the posts.

Magazine editor Tucker Shaw wrote the series of tweets after overhearing a conversation about how the 1980s epidemic in the US—which saw tens of thousands die—made life better for the LGBT+ community “in the long run.”

Shaw wrote: “I overheard a young man on the train on the way home today, talking to another young man. Holding hands.

“In college, I guessed. About that age anyway. Much younger than I am.

“He was talking about AIDS, in a scholarly way. About how it had galvanised the gay community. How it had spurred change. Paved the way to make things better, in the long run.

“The long run.”

The thread has received around 100,000 retweets and likes (tucker_shaw/twitter)

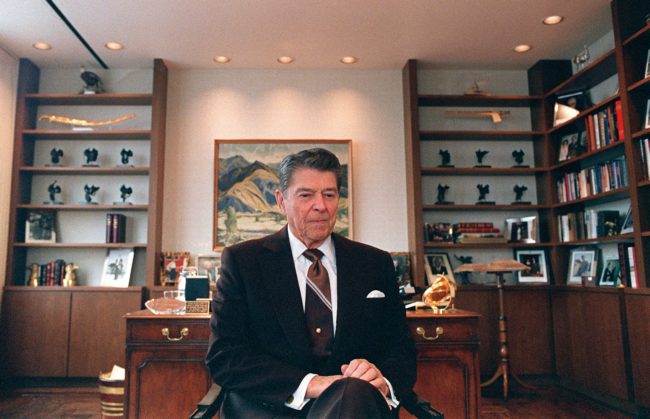

The disease ravaged the community as countless media outlets and politicians stayed silent over what was seen as a “gay disease,” with one chilling recording featuring President Ronald Reagan’s press secretary laughing after being asked about gay people’s deaths.

Reagan did not mention AIDS in public until 1985, when 5,000 people—primarily gay and bisexual men—had already died.

President Ronald Reagan (CARLOS SCHIEBECK/AFP/Getty)

Affected by the young man’s remarks, Shaw recounted with painful detail what it was like to exist as a member of the LGBT+ community in the US at the time, from visiting sick friends in hospital to dealing with the grief of losing loved ones.

“Remember how terrible it was, not that long ago, during the worst times. How many beautiful friends died.

“One after the other. Brutally. Restlessly. Brittle and damp. In cold rooms with hot lights. Remember?

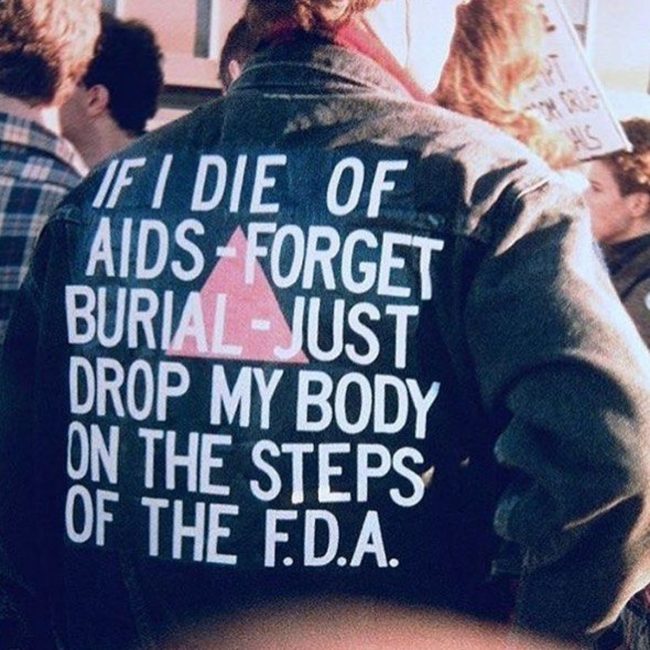

An activist makes his views on the FDA clear (Wikimedia Commons)

“Some nights, you’d sneak in to that hospital downtown after visiting hours, just to see who was around. It wasn’t hard.

“You’d bring a boom box. Fresh gossip. Trashy magazines and cheap paperbacks. Hash brownies. Anything. Nothing.

“You’d get kicked out, but you’d sneak back in. Kicked out again. Back in again. Sometimes you’d recognise a friend. Sometimes you wouldn’t.

“Other nights, you’d go out to dance and drink. A different distraction. You’d see a face in the dark, in the back of the bar. Is it you? Old friend! No. Not him. Just a ghost.”

“You’d get kicked out, but you’d sneak back in.” (tucker_shaw/twitter)

“At work, you’d find an umbrella, one you’d borrowed a few rainstorms ago from a coworker. I should return it, you’d think. No. No need. He’s gone. It’s yours now.

“Season after season. Year after year. One day you’d get lucky and meet someone lovely. You’d feel happy, optimistic. You’d make plans.

“Together, you’d keep a list of names in a notebook you bought for thirty cents in Chinatown so you could remember who was still here and who wasn’t, because it was so easy to forget.

Queer people struggled to get any authorities to care about the epidemic (MarkGHWestall/twitter)

“But there were so many names to write down. Too many names. Names you didn’t want to write down. When he finally had to go too, you got rid of the notebook. No more names.

“Your friends would come over with takeout and wine and you’d see how hard they tried not to ask when he was coming home because they knew he wasn’t coming home. No one came home.”

Emphasising the youthful nature of so many of the epidemic’s victims, he wrote: “You’d turn 24.

“When he’d been gone long enough and it was time to get rid of his stuff, they’d say so. It’s time. And you’d do it, you’d give away the shirts, sweaters, jackets. Everything.

“Except those shoes. You remember the ones. He loved those shoes, you’d say. We loved those shoes. I’ll keep those shoes under the bed.

“You’d move to a new neighbourhood. You’d unpack the first night, take a shower, make the bed because it’d be bedtime. You’d think of the shoes. For the first time, you’d put them on. Look at those shoes. What great shoes.

An AIDS protest in 1998, in front of the White House (JAMAL A. WILSON/AFP/Getty)

“Air. You’d need air. You’d walk outside in the shoes, just to the stoop. You’d sit. A breeze. A neighbour steps past. ‘Great shoes,’ she’d say. But the shoes are too big for you.

“You’d sit for a while, maybe an hour, maybe more. Then you’d unlace the shoes, set them by the trash on the curb. You’d go back upstairs in your socks. The phone is ringing. More news.”

“The long run. Wasn’t that long ago,” he concluded.

The thread, which attracted around 100,000 retweets and likes, received hundreds of responses, many from users who also lost people close to them during the crisis—friends, brothers, fathers, uncles and cousins.

One wrote: “When I was I guess 14, Mom told me my uncle John had HIV. My big, strong uncle John – we have pictures of him swinging my sister and I around on the National Mall, one in each hand, like a carousel.

“I was SO angry. Still am. I hadn’t spent enough time with him. Still haven’t.”

Others recounted family members, schools, churches and other institutions which had rejected, abandoned and isolated people with HIV/AIDS.

Countless people lost loved ones (twitter)

Last year, bisexual actor Alan Cumming said many young people don’t want to hear about the AIDS crisis.

He said: “I know so many older gay men who are like: ‘You don’t know what the Aids crisis was like,’ but I also know a lot of young gay guys who are like: ‘Who cares?'”