‘Homophobic bullying made me suicidal and depressed’

Olivia McMahon (left) and Ryan Campinho Valadas both say anti-gay bullying contributed to their mental health problems. (Olivia McMahon/James Johnson Barber)

To mark Anti-Bullying Week, LGBT+ activists have revealed how homophobic bullying left them depressed, self-harming and suicidal—even after leaving school.

“For the first two years, probably until the end of the third, it was horrendous,” Olivia McMahon tells PinkNews.

“I was getting called names, I was getting rubbish thrown at me.”

McMahon became the victim of homophobic bullying when she was outed as gay soon after starting secondary school just north-east of Glasgow, Scotland.

She says she was soon taunted with “just the usual” anti-gay insults, such as “dyke” and “faggot.”

McMahon explains that, because she went through a tomboy phase, some of the other students thought she was trans and began subjecting her to transphobic slurs, like “he-she.”

“I was the classic bully victim,” adds McMahon. “I was small, I was gay, I had red hair, I kind of stand out anyway.”

Shocking homophobic bullying statistics

The statistics back up McMahon’s account that anti-gay slurs are commonplace in UK schools.

A 2017 report by Stonewall found that nearly half (45 percent) of LGBT+ pupils in Britain were bullied over their sexuality or gender identity at school—and more than one in two LGBT+ students reported hearing homophobic language “frequently” or “often” during their primary or secondary education.

The vast majority of LGBT+ pupils—86 percent—said they regularly hear phrases like “that’s so gay and “you’re so gay” at school.

As well as being called names, McMahon remembers being treated differently by her classmates, particularly the other girls.

“I remember in PE, when we were in the changing room, girls would fear that I would staring at them,” she explains. “[It was] people not looking at me, the girls not wanting to hug me, all that kind of thing.”

Olivia McMahon says she self-harmed after getting bullied at school. (Image courtesy of Olivia McMahon)

McMahon says that her teachers didn’t intervene in the bullying because they didn’t know how to respond to it.

“It was something obviously they weren’t really trained in,” she says, “they didn’t know how to cope with it.”

McMahon believes that there is a direct link between her struggles with mental health and the bullying she received.

“I had a lot of issues. I was self-harming,” she explains.

“I’ve got PTSD now, to do with that [and] to do with other things that happened in my life. I was struggling not only with being bullied, and obviously my sexuality, but I had a lot of other issues going on. It didn’t help my self-esteem. Even now, I don’t have any close friends really, I just kind of mingle with everyone but don’t let anyone in.”

“Leaving school was probably the best thing that could have ever happened to me.”

— Olivia McMahon

Now 18 years old, McMahon remembers her school days as a dark period in her life, made markedly worse by the bullying she received.

“To be honest, leaving school was probably the best thing that could have ever happened to me,” she continues.

Parts of McMahon’s story are echoed by Ryan Campinho Valadas, 31, who went to school in a suburban area in Lisbon, Portugal.

Valadas, who later moved to London, was bullied from aged 10 onwards.

Like McMahon, this began with name-calling (“it would be the English equivalent to words like sissy, or faggot,” he says).

However, Valadas adds, this could escalate into physical confrontations.

“I used to sometimes be assaulted in toilets, which I grew to view as a very dangerous place,” he says.

“I often asked to go to the toilets during class, rather than during breaks because, it was quite easy to gang up on someone in the toilet and hit them in a group.”

Ryan Campinho Valadas was attacked for being gay at school. (James Johnson Barber)

Homophobic bullying led to suicidal thoughts and depression

Rather putting a stop to the bullying, Valadas says his teachers sometimes joined in.

Things got so bad, he says, that he had to stay at school long after it had finished to wait for a lift back “so that I could get home safely.”

Like McMahon, Valadas says anti-gay bullying had a hugely detrimental impact on his mental health.

“[I was] quite depressed, I was suicidal for quite a long time, and often found myself trying to think of ways in which to go ahead with suicide,” he explains.

“That was a big part of my adolescence, managing those kind of thoughts, and really not feeling like anyone would be available to speak to me.”

“Later on, I didn’t have a lot of self-confidence for many years and operated on very low self-esteem.”

— Ryan Campinho Valadas

Valadas says his experience of bullying overshadowed his adult life, when he started doing drugs in an attempt to deal with what happened to him.

“Later on, I didn’t have a lot of self-confidence for many years and operated on very low self-esteem,” he says.

“I ended up engaging in a lot of substance misuse in my late teens and early twenties as a result of not being able to be in social groups without needing a little bit of help from a substance.”

The research supports Valadas and McMahon’s reports about the detrimental impact bullying has on mental health.

Earlier this year, the Annual Bullying Survey concluded that 62 percent of young LGBT+ people in the UK have had suicidal thoughts because of bullying–and more than seven in 10 (71 percent) said that it had led to depression.

A further 70 percent said bullying had left them with social anxiety.

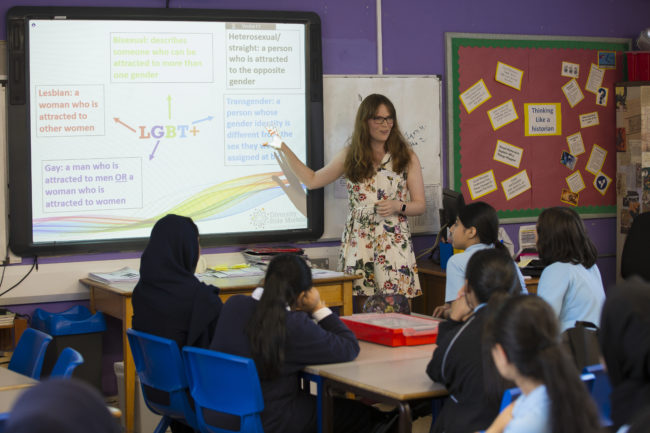

Diversity Role Models running a diversity workshop in a school in London. (Diversity Role Models)

Both McMahon and Valadas have turned to activism to help ensure more LGBT+ children don’t hate school like they did.

In Glasgow, McMahon has worked with campaign group Time for Inclusive Education (TIE), which has successfully lobbied for LGBT+ content to be taught in all schools in Scotland, making it the first country in the world to do this.

Valadas, meanwhile, volunteers with Diversity Role Models in London, where he leads workshops in schools to education kids on LGBT+ issues and combat anti-gay bullying.

Valadas, who also works as a full-time therapist, says the workshops he runs are something he “would have benefited from if this sort of thing had existed at school.”

He adds: “Everyone is just really curious and interested and they often ask really pertinent questions. It really makes me think that people don’t give enough credit to young people and actually they’re quite able to form their own opinions and ask relevant questions if they’re given the chance to do so.”