This gay photographer lost countless friends and loved ones to AIDS. He feared he would be next

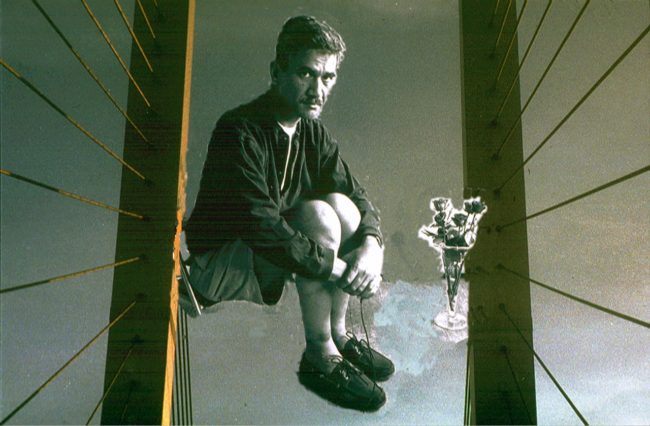

Sunil Gupta at home in New Delhi in 2007. (Courtesy of Sunil Gupta)

“I went into this melodramatic moment of ‘I’m in these pleasant surroundings, with a lot of people. But I’m dying,'” photographer Sunil Gupta tells me, as he recalls being diagnosed as HIV-positive on July 20, 1995.

He remembers walking outside St Thomas’ Hospital in central London on that sunny day, surrounded by the lunchtime hubbub, and looking over the River Thames.

“It was like I was in my own movie suddenly. That made me weep a bit. And I didn’t know how to being to tell anyone, either,” Gupta adds.

Now 65 years old, Gupta has been living with HIV for more than 20 years.

Sunil Gupta talks to us for World AIDS Day

To mark World AIDS Day on December 1, Gupta is speaking to me about his experience of the HIV/AIDS crisis through the 1980s and 1990s, which devastated the gay community.

It’s estimated that nearly 37 million people are living with HIV globally and more than 35 million people have died from AIDS-related illnesses across the world since the outbreak of the pandemic.

Throughout our hour-long conversation in his studio in Camberwell, Gupta talks about how his friends died around him—how he lost so many that funeral rites became a source of “great interest and debate” and, even, black humour. (“I think that’s a very positive gay response to whenever we’ve been in trouble as a group of people,” he notes.)

Born in 1953 in New Delhi and raised in Montreal, Gupta moved to London from New York in late 1977, a few years before the virus hit the UK.

Photographer Sunil Gupta on the day he was diagnosed with HIV on July 20 1995. We talk to him now for World AIDS Day 2018. (Courtesy of Sunil Gupta)

He explains how, at first, in the early 1980s, AIDS seemed liked an “American problem,” adding: “That, somehow, being in the UK, we were safe.”

“The number of deaths started to pile up. The frequency just grew somehow.”

—Sunil Gupta

But, from about 1983 onwards, the virus started to spread quickly among his social circles.

“The number of deaths started to pile up. The frequency just grew somehow,” says Gupta. “It became a kind of new normal.

“It went from this great ignorance to a panic to a kind of stage of acceptance, but with a kind of black humour attached to it.”

Gupta recalls how the virus claimed the lives of his friends, including film director Stuart Marshall, who was widely praised for his work documenting the HIV/AIDS crisis, in 1993.

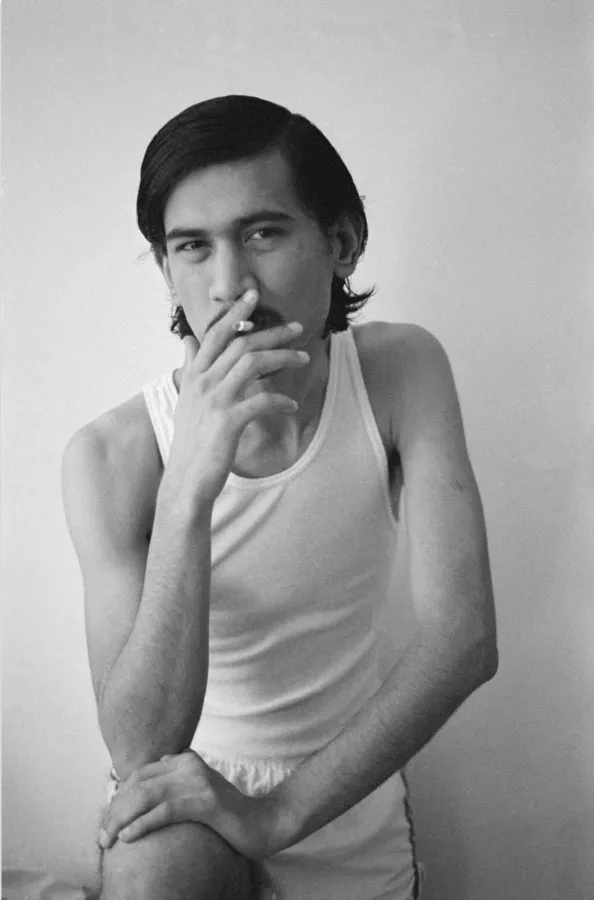

Sunil Gupta in Montreal in the 1970s. (Courtesy of Sunil Gupta)

In particular, Gupta remembers the death of his close friend Peter, a school teacher, who died suddenly from AIDS after he went on a field trip to Wales and caught what initially seemed like a cold.

“All he did was go out in the rain with these school girls,” he says. “It just didn’t seem right somehow.”

Sunil Gupta tells PinkNews his story on World AIDS Day

Gupta explains that at Peter’s funeral there was a clear seating divide with the family at the front and “us, the gay male friends, in the back.”

During the service, Peter’s family made a speech where they blamed Gupta and his friends for their son’s death.

“They were pretty much accusing us of having killed their son. It was really unpleasant. They were not happy at all,” says Gupta.

“[They were saying] we had caused it, and that if he hadn’t come to London and hadn’t met us, somehow, that we’d led him to this.”

Saturday December 1 marks the 30th anniversary of World AIDS Day. (Robert Taylor)

The tabloid media, he says, fuelled this anti-LGBT+ rhetoric by blaming gay “lifestyles,” such as being “too promiscuous,” for the spread of the virus.

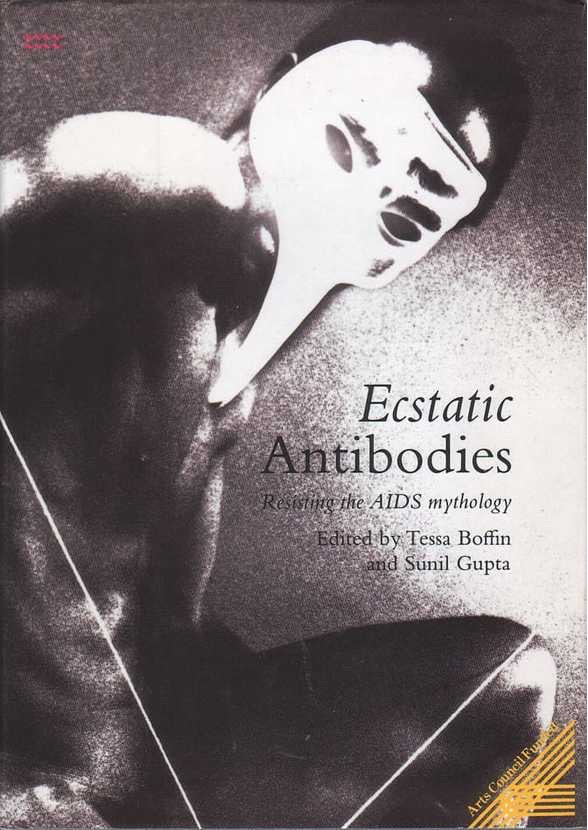

In 1990, Gupta took a stand against this demonisation of gay men through his work and published a pro-queer book called Ecstatic Antibodies with lesbian photographer Tessa Boffin about the portrayal of the AIDS crisis in the UK.

However, the photographer says that he still didn’t get tested. Among his peers, there was a general view of “there’s no point getting tested because there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Indeed, when azidothymidine (AZT), the first treatment for HIV, came along in the late 1980s, Gupta says the debate over the effectiveness drug divided his friends “almost like Brexit.”

“Suddenly my friends were in one camp or the other,” he adds. “Tragically, it didn’t seem to matter because both people died, with and without.”

In 1995, Gupta went to get a test after his then partner, who had just met, asked about his status.

He says that, following his diagnosis, all his friends “shared my feeling that I was going to die.”

Sunil Gupta and Tessa Boffin’s book Ecstatic Antibodies. (Courtesy of Sunil Gupta/Rivers Oram Press)

He laughs. “Then it got embarrassing because I realised after a few days that I’m not going to die, like not so instantly. Because I was actually quite well.”

Gupta was prescribed various antiretroviral medicines at St Thomas’ Hospital and at first continued life much as before.

Sunil Gupta on falling ill after his HIV diagnosis

But, in 1999, a few years after his diagnosis, Gupta fell ill and his changing body made him feel “very unattractive.”

He developed lipohypertrophy, caused by the antiretroviral drugs he was taking, which resulted in a fat build-up on his stomach.

“I was virtually signing on and living in a council flat. It got really, pretty as low as you can get.”

—Sunil Gupta

“I just stopped everything and let it all go,” he says. “I had a long-ish period of self-induced isolation.”

Gupta stopped going to the gym and meeting up with friends. His work life, too, “slid down hill” because he wasn’t doing anything.

“I was virtually signing on and living in a council flat,” he says. “It got really, pretty as low as you can get.”

Gradually, Gupta managed to get back on his feet. He got a dog, which he says “saved” him, and joined a mentoring scheme at Terrence Higgins Trust.

In 2000, he won a three-year scholarship, which he used to return to India and create whole exhibition called Love and Light, documenting HIV in the country in 2004.

Sunil Gupta’s Love and Light exhibition in India in 2004. (Courtesy of Sunil Gupta)

“I was very enthused by it,” he says of the project. “It kind of woke up me up…it also saved my bacon because it gave me a subject to really get involved with.”

In 2009, he went to an AIDS meeting in Delhi, where he met his now husband Charan Singh, who was a social worker.

Now, settled in the UK, Gupta, who is on an improved combination of HIV treatment, is enjoying a new lease of life (except for having to pay off the debt he never thought he’d live to deal with).

Today, numerous studies have underpinned the Undetectable = Untransmittable or “U=U” campaign—if a person with HIV is on effective treatment, so that they have an undetectable viral load, the virus cannot be transmitted to another individual.

“I’m 65 and it’s like I’m feeling like I’m back at 40, and things are happening again…I’ve had to rethink my life and restart,” he says, smiling. “I don’t think it’s going to kill me. Something else will.”