The highs, the lows and the backlash: Looking back on the last decade of the fight for trans rights in the UK

Trans campaigners marching at Manchester Pride, 2019. (Tina Williams)

Ten years ago, the world didn’t know what being a non-binary trans person meant – yet by the end of the decade, the dictionary had named the singular ‘they’ pronoun the word of the year. How did trans rights get here?

‘I came out in 2009,’ says Toryn Glavin, Stonewall’s trans engagement manager. ‘I was 15, and I just came out as a woman – because I didn’t know what the word “trans” meant.’

It’s unlikely to be an experience shared by a trans person coming out today. From Sam Smith coming out as non-binary and genderqueer to Laverne Cox in Orange Is the New Black and Caitlyn Jenner on I’m a Celebrity, trans and non-binary people are more visible than ever before.

“They’re not always positive stories, they’re not all positive role models, but they’re there, and that’s really important,” Toryn says. “That visibility leads to real change.”

Sam Smith is winning 2020. (Instagram/Sam Smith)

Life for the trans community in the UK has been somewhat tumultuous in the last decade.

As well as important and positive legal changes, like being protected from discrimination by the 2010 Equality Act, there have been big steps forward for the community in terms of representation in popular culture and the sense of community itself, with Europe’s first-ever Trans Pride event, in Brighton, starting in 2013 and London seeing its own Trans Pride in 2019.

But one step forward has often felt like it’s been followed by two steps back.

UK newspapers are arguably the most viciously transphobic in the world, with anti-trans articles written by straight, cisgender journalists regularly dehumanising and attacking trans people, accompanied by a steady trickle of the few trans journalists working in the national media leaving en masse, citing institutional transphobia and anti-trans discrimination.

On top of this, hate crimes against trans people have quadrupled since 2015. Violence against the LGBT+ community – particularly against trans women of colour – is a real and continuous threat.

Thousands of transgender people and their allies take to the streets for London’s first ever Trans+ Pride march on 14 September, 2019. (WIktor Szymanowicz/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Vital reforms to the way trans people change the gender on their birth certificates have been repeatedly delayed, creating a vacuum into which the media and “gender-critical feminists” have fed anti-trans lies and misinformation.

“Gender critical feminists”, the preferred guise of transphobes in the latter half of the decade, tried to portray trans people as predatory villains seeking to abuse women and women’s rights.

When those attempts failed, they said that rights for trans people would be abused by predatory men looking to attack women. And, finally, when people saw through that, they said that trans people were dangerous to children. This moral panic – reminiscent of the gay moral panic of the 80s – can make being trans feel very difficult.

Headlines about trans people in UK papers, 2018.

It’s easy for trans people who came out during this decade and have been on the internet to feel as though the world hates us. It’s easy to feel like everything is going backwards. But that’s not quite the case.

The progress of trans rights in the last decade.

At the beginning of the decade, the 2010 Equality Act came into being. This replaced hundreds of the UK’s anti-discrimination laws – which protected individuals from unfair treatment on the basis of things like race, religion, age and sexual orientation – and brought them all under a single act.

For the first time, transgender people gained legal protection from discrimination when “gender reassignment” became one of the nine new “protected characteristics”.

“I think we hit peak equality in 2010,” says Christine Burns, author of Trans Britain: Our Journey From The Shadows and a former vice president of Press for Change, the trans rights campaign group that was behind the original Gender Recognition Act in 2004.

“There was so much going on and there was so much optimism, there was so much that was ‘can-do’ – doors were opening left, right and centre in 2010,” she says.

Christine Burns, trans campaign and former vice president of Press For Change.

Legal changes weren’t the only positive things happening for the trans community at the beginning of the decade.

In 2013, a group of friends in Brighton got together and started Europe’s first-ever Trans Pride event – a protest that has grown from seeing 800 people attend in its first year to 8,000 people last summer.

“There were a few of us who were like, ‘I don’t want to go to Brighton Pride, it’s not a safe space for transgender people’,” says Sarah Savage, children’s author and founding member of Brighton Trans Pride.

“So there were four or five people who got together in April of 2013. There was me, there was Fox Fisher, Steph Scott, Sabah Choudrey and Phoenix Thomas,” she says.

Others reached out to Brighton Council’s LGBTQ Workers’ Forum, who, along with a Brighton Pride employee, helped as the DIY operation applied for licenses, made a space for Trans Pride at Brunswick Square Gardens and promoted the event on social media.

Trans Pride Brighton 2014. (Facebook/Sharon Kilgannon, alonglines.com)

“It was amazing,” Sarah says of that first event in July 2013. “It was a seminal moment in Brighton. We were in the middle of St James Street, the gay quarter, and we were reclaiming that s**t for ourselves.”

“It felt very subversive. It really felt like we were coming together as a whole community. There were people who came from all over the UK that turned up to that first one, it was mind-blowing,” she says.

Brighton Trans Pride, Sarah says, is a protest – it’s not about “raising awareness” of trans people, it’s about supporting and making space for the most vulnerable members of the community.

“Trans people are discriminated against by society and we needed to make a point about that. We’re still making that point seven years later.”

And other cities followed suit with Trans Pride events: Bristol, Leeds, Belfast and London, as well as Trans Pride Scotland, which last year was held in Dundee.

Ask any transgender person who’s been and they’ll tell you that Trans Pride is special. In Brighton, Sarah says this is because Trans Pride is by trans people, for trans people.

“If it’s not trans-led, it’s not authentic,” she says. “Only a trans person knows what it feels like to walk down the street and feel like everyone is looking at them because they feel different.

“Only a trans person can know how to make that person feel included in a group and how to feel accepted. That’s why other pride events, gay pride events, worked so well for gay people – because they were led by gay people.

“I think trans people have the power to curate a space where only they know what they need.”

London’s first-ever Trans Pride. (WIktor Szymanowicz/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Then, halfway through the decade, Europe’s biggest and most well-respected LGBT+ charity, Stonewall, became trans-inclusive. This was, Toryn says, “an incredibly important moment.”

“Ruth Hunt and the Stonewall leadership acknowledged that they were very late to this party, almost to the point where they no longer had a standing invitation,” Toryn says.

“They couldn’t just walk in at that point, they actually had to ask. And in fairness they did that, and they consulted with more than 700 trans people, and overwhelmingly the answer was, you have the power, you have the privilege and you should be using that to help us and that’s what we want.

“I think that was the right way of doing things,” she says. “I’m really glad they did it and I think it’s really important.”

Marchers at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride event, Piccadilly, London, 4th July 1998. One marcher is holding a Socialist Worker placard, calling for the scrapping of Section 28. (Steve Eason/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Toryn worked in trans-specific organisations before joining Stonewall, to work on its engagement with the trans community in the UK, when it began campaigning for trans rights in 2015.

Stonewall’s work on this has included its 2017 Vision for Change – a five-year manifesto of what it wants to achieve for trans rights, which was created through asking the trans community what it needed from Stonewall.

One of these things was reform of the UK’s gender recognition laws, which Press for Change had helped shape all the way back in 2004.

Trans rights: Reforming the Gender Recognition Act.

The process by which transgender people change the gender on their birth certificate has been in place for 16 years, meaning that what was originally a groundbreaking piece of legislation is now out of date in certain ways – it doesn’t include non-binary trans people, and it requires medical evidence before a trans person can change their legal gender (the World Health Organization stopped categorising being trans as a mental disorder in 2019).

This means that, despite the UK’s transgender population being commonly estimated as including up to half a million people, fewer than 5,000 have used the GRA to change their legal gender – with many trans people saying that they haven’t done it because it’s expensive, overly bureaucratic, and the amount of medical evidence required to apply is intrusive and unnecessary.

In 2017, then-prime minister Theresa May announced – at the PinkNews awards – that the Conservatives would reform the GRA to de-medicalise the process, saying that “being trans is not an illness”.

Then, in 2018, the government finally held a public consultation on the proposed changes – asking for people’s views on things like lowering the age at which transgender people can change their legal gender from 18 to 16 and extending legal recognition to non-binary transgender people.

More than 100,000 people filled out the consultation, but the results are yet to be released. In July 2019, then-equalities minister Penny Mordaunt said – this time at the PinkNews summer reception in Westminster – that the results of the public consultation would be “out the door in the next few weeks”.

But in the last six months of political turmoil, GRA reform has slipped off the political radar. And in the three years since May announced the reforms, anti-trans media and “gender-critical feminists” have put out vast amounts of misinformation into the vacuum created by a lack of movement from the government, framing GRA reform in untrue and negative ways.

“I don’t think we thought that, three years down the line, we’d still be talking about it,” Toryn says. “It’s such an unexpected backlash to something that was a simplification of an administrative process.”

In Scotland, the situation is slightly different – they had their own separate consultation on potential GRA reforms, and the government has published a draft gender recognition bill. But despite 60 per cent of the public agreeing with the proposal to introduce a self-declaratory system for legal gender recognition, during a 2017-18 public consultation, there is a second consultation on the new draft bill.

Plus, some potential reforms have already been discounted in Scotland – including the government saying it will not extend legal recognition to non-binary people.

Scotland has launched a consultation that will affect trans people's access to Gender Recognition Certificates

Be an ally ➡️ https://t.co/sFswRDXoMO pic.twitter.com/Skef9lrJ5Q

— PinkNews (@PinkNews) January 8, 2020

GRA reform, Toryn says, is about accessibility: “It’s about making sure working class trans people and poor trans people and non-binary people and trans young people can all access this service – which is essentially an administrative change – in the same way.”

“It’s so wild to me that there is such an objection to gender recognition reform, because the legislation’s been in place since 2004 and all we’re looking for is a simplification of the process, and a process that’s more inclusive of a wider range of identities,” Toryn says.

“We’re not really asking for anything that hasn’t been happening in this country for 15 years.”

Anti-transgender backlash.

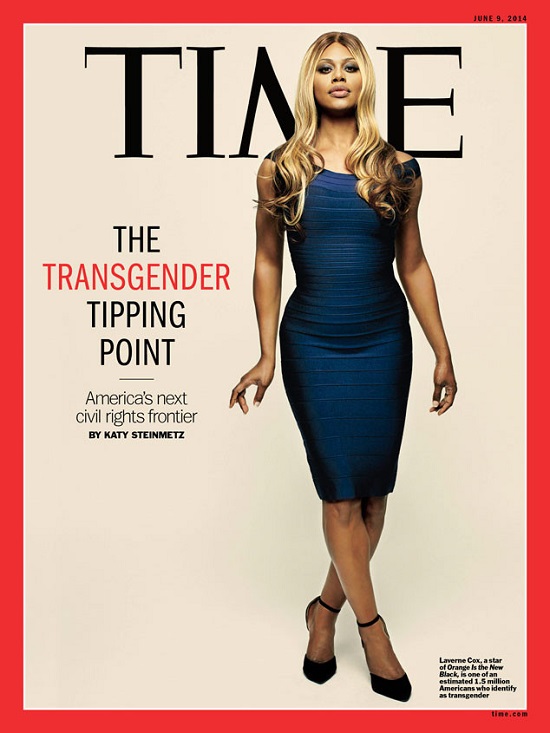

In 2014, the “transgender tipping point” – starting with Laverne Cox on the cover of Time magazine – saw trans people and trans rights thrust into the public limelight.

This drew “a big target on our back”, Christine says, especially because in 2015, the US religious right lost their battle against marriage equality when the US Supreme Court legalised same-sex marriage.

“If you’re going to keep a following together, you have to give them something to hate – and I think we were there, saying ‘hey, we’re here!’ just at the time they [the US religious right] were looking for something to campaign against,” Christine says.

Laverne Cox on the cover of Time magazine, 2014.

In the UK, trans people were barely in the media before this point. But in the last half of this decade, media coverage of transgender people – usually written by white, straight, cisgender journalists – has sharply increased, with anti-trans articles appearing in all the major national newspapers on a regular basis.

And when, in 2019, anti-bullying charity Ditch the Label investigated 10 million public online posts over the course of three and a half years to better understand hate speech, it found that 1.5 million contained transphobic language or abuse.

“It’s very similar to what happened at the formation of Stonewall, which was in opposition to Section 28, when we saw the dehumanising of lesbians and gay people in the media,” Toryn says.

“Now, parts of the media are painting this division between lesbian groups and trans groups,” she says.

“It’s a very small, niche, fringe group of anti-trans activists. We see hateful people come out against every marginalised group.”

But, she adds, “the love and support we’ve seen from the vast majority of lesbian and bi communities and women’s groups has been quite amazing.”

Comedian Rhona Cameron and political activist Peter Tatchell help to hold a banner at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride event, London, 4th July 1998. The banner calls for an end to Section 28 which refers to the teaching and promotion of homosexuality by local authorities. ( Steve Eason/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Resistance, allyship and hope for trans rights.

In 2018, a small group of anti-trans activists hijacked the front of Pride in London and marched at the front of the parade. This made the organisers of Trans Pride Brighton – being held a few weeks later – incredibly concerned about safety at their event.

But what was amazing, Sarah says, is that the anti-trans protestors “spurred cis allies into action” – within three weeks, they had more than 200 volunteers to keep people on the march safe.

“On the face of it, anti-trans protesters, or the threat of it, was scary,” Sarah says.

“But what actually happened was an amazing display of solidarity from cis allies and an amazing display of defiance from trans and non-binary people saying, ‘We’re here and we’re not going to change our plans based on the threat of some idiot anti-trans person.

“We’re not going anywhere.”

Pro-transgender group L With The T lead the Brighton Trans Pride protest march in 2018. (Facebook/TransPrideBrighton)

Though it can be hard to escape the anti-trans rhetoric in the media and online, and it can feel dangerous – it is dangerous – to be transgender in public, history suggests that the current moment we’re in is a blip.

Christine – who has been a trans rights campaigner since the 90s – thinks that these “mini-backlashes” are a phenomenon of the human race, which follow any progress in terms of rights for a marginalised group. Then, she says, “we move forwards again.”

Sarah agrees: “Trans people have been saying the same thing since the beginning of time. I know trans activists who were around in the 1980s and they were campaigning for the same things: proper access to healthcare, the ability to change our birth certificates, genuine actual representation in the media. Some of that has started to happen. And it will happen over the next 10 years.

“We’re in our stride within our community to demand the same rights. I think the next decade will being trans and non-binary into the mainstream and into acceptance.”

Toryn says that, since she came out at the beginning of the decade, rights and equality has become a lot better for trans people.

“I know things are scary, but this decade has been incredible for our community and I think the next decade will be even better,” she says.

“We’re in a bit of a scary place now, but we’ll get out of it, and we’ll be stronger together.”