Victim of brutal London bus attack that shocked the world explains why misogyny needs to be treated as a hate crime. Now

Melania Geymonat (right) and her partner Chris Hannigan were beaten on a London bus for refusing to kiss and perform sex acts. (Facebook)

A victim of a 2019 London bus attack that rocked the LGBT+ community has joined calls to make misogyny a hate crime as a new report highlights the need for intersectionality in policing.

Melania Geymonat and her partner Christine Hannigan made headlines in June 2019 when they were beaten by a group of teens on a London night bus for refusing to kiss. The image of the couple covered in blood shocked the nation, sparking a conversation about how unsafe LGBT+ people often feel in public.

Now Geymonat is adding her voice to a campaign by Citizens UK to make misogyny a hate crime, so that the common intersectionality of homophobia and sexism will be recognised by police and the courts.

“I was really surprised this intersectionality is not even considered, because it’s pretty obvious for me,” she told PinkNews. “I had no doubt about what happened: we were attacked because we were together, but also because we were women.

“I don’t know what came first, misogyny or homophobia, because it’s both at the same time. So for me, it’s a huge mistake not to recognise that. We are never one thing alone, we are the intersection of many different aspects of our identities, and the law must reflect that.”

A group of teens targeted Melania Geymonat and Christine Hannigan in the London bus attack. (Metropolitan Police)

A new study released Thursday (September 10) by Citizens UK shows that 45 per cent of women have been threatened with sexual violence, compared with 16 per cent of men; while 43 per cent of women had suffered a sexual assault, compared with 12 per cent of men.

Despite women being more frequent targets for hate-motivated attacks because of their gender than men, there is no consistent way for victims to report misogyny under current UK hate crime laws.

Pressure is now growing for this to change. The proposal is supported by retired police chief constable Sue Fish, who introduced the reporting of misogyny as a hate crime in Nottinghamshire in 2016.

“Making misogyny a hate crime was one of the simplest tasks I’ve ever done working in the police — and yet the results that we saw were incredible,” she said. “Some of the feedback we had was that women, for the first time, described themselves as walking taller and with their ‘heads held high’.”

Fish expected the uptick in women’s sense of safety, but she didn’t expect that to be shared by young men, many of whom chose to go to university in Nottingham because they felt “if women will be safe here, men will be safe here too”.

The changes were apparent within Nottinghamshire’s “predominantly male, white, heterosexual” police force, too.

“Their idea of what a victim was like suddenly became very different,” Fish said. “It also became a mechanism to challenge unprofessional behaviour and to have a different conversation, not just about sexism, but about the impact of behaviour and language in general.”

It’s about allowing victims to say: ‘This is happening to me because I am a trans woman, not just because I am trans.’

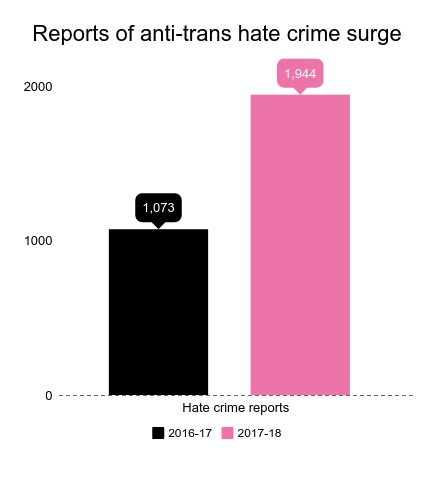

Fish hopes the effect of the proposed change will be an improvement in policing of anti-LGBT+ hate crimes, in particular those against transgender women, who often fall at the unfortunate intersection of misogyny and transphobia.

“It’s about allowing victims to say: ‘This is happening to me because I am a trans woman, not just because I am trans.’ Whereas what’s been reported previously would have been very one-dimensional, if at all,” she said.

“Although there isn’t a double whammy in sentencing, classing misogyny as a hate crime does give the police two bites of the cherry to get it right. It gives victims more help and legitimises this awful experience they’ve had.”

Hate crime laws ‘must reflect the complexity of people’.

Only seven of 46 English and Welsh Police forces currently undertake local reporting on misogyny or gendered hate crimes — a discrepancy that’s reflected in the unequal experiences hate crime victims often feel when reporting to the police.

Melania Geymonat and Christine Hannigan are well aware of this. Shortly after the attack Hannigan acknowledged that as white, femme, cisgender women, police were happy to roll out the red carpet for them, but trans women reporting the same crime often do not experience the same treatment.

“Our story had this huge impact without even being the most serious one, not even by one inch, if we actually compare it to the violence that [trans women] have to put up with,” Geymonat told PinkNews.

“We were the exception and not the rule. So my question would be, what if we were the rule? What if the attention we had could be given to other victims of hate crime?”

Fish is keen to point out that criminalising misogyny would complement existing hate crime laws, not supersede them, understanding the fact that misogyny is a common thread running through many different forms of targeted abuse.

“This isn’t about minimising homophobic or trans male attacks at all — this is about recognising there is something very fundamental that happens with women that doesn’t happen with men,” she explained.

“With this particular sort of abuse, it’s not because they’re a man and gay, it’s because they’re a woman and gay. And that’s not to diminish the awfulness of homophobic attacks that happen everyday to men, it’s about uncovering a new level of the abuse.”

She continued: “We often see hate crimes in a binary way, thinking it either is one or it isn’t, and you can only tick one box at once. But there’s a complexity there — people aren’t straightforward or binary, so we need legislation and consequences that reflect the complexity of people.”