Few LGBT+ people dared question heterosexual supremacy 50 years ago. The Gay Liberation Front changed that

(Peter Tatchell)

Peter Tatchell was an activist in the London Gay Liberation Front five decades ago. Writing for PinkNews, 50 years to the day since the group was first founded, he looks back at the pioneering movement that helped create the modern LGBT+ community and changed society forever.

We’ve come a long way, baby!

Fifty years ago, on October 13, 1970, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was founded at a public meeting at the London School of Economics, attended by 19 people.

Within weeks, it snowballed into meetings attended by hundreds more. Those brave pioneers kick-started a movement that challenged the bigotry of centuries. They ignited the modern movement for LGBT+ rights.

GLF was a defining, watershed moment in UK queer history. For the first time ever, thousands of LGBT+ people stopped hiding in the closet and suffering in silence.

We came out and marched in the streets, proclaiming that we were proud to be LGBT+ and demanding our liberation from straight tyranny. This had never happened before.

(Peter Tatchell)

In 1970, many LGBT+ people were ashamed of their sexuality and gender identity. They kept it hidden and often wished they were straight or cisgender.

Some went to quack doctors to get “cured”. Many accepted the bigot’s view that being “queer” was inferior and second best.

Back then, the law branded gay sex as unnatural, indecent and criminal.

Despite the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1967 in England and Wales, most aspects of queer male life remained illegal.

Arrests and convictions rose by 400 per cent in the early 1970s. Plus, it was lawful to discriminate against us in employment, housing, education, advertising and healthcare.

The Catholic Church condemned homosexuality as immoral, wicked and sinful and the medical profession classified us as sick, abnormal and disordered.

Queers were sacked from their jobs and arrested for kissing in the street. Lesbians who had married men out of social pressure were declared unfit mothers and denied custody of their children in divorce cases.

Anti-LGBT+ violence was rife and some police dismissed homophobic attacks, saying: “What do you expect if you’re a bender?”

Straights vilified, scapegoated and invisibilised us – with impunity.

LGBT+ people were rarely portrayed in films and on TV, and even then it was almost always negatively. Gay men were depicted as limp-wristed figures of ridicule. We only ever appeared in the news when unmasked as murderers, spies, traitors and child molesters.

Straights vilified, scapegoated and invisibilised us – with impunity. Few LGBT+ people dared question heterosexual supremacy 50 years ago.

Indeed, prior to GLF, most LGBT+ rights campaigners masqueraded as straight, and many pleaded for tolerance rather than acceptance.

Some argued that we needed “help”, not criminalisation. They urged heterosexuals to show compassion for those “afflicted” by the “homosexual condition”.

This apologetic, defensive and victim mentality was rejected by GLF and replaced with pride and defiance. It transformed attitudes among both LGBT+ and straight people.

(Peter Tatchell)

Inspired by the Black Power slogan “Black is Beautiful”, GLF came up with a slogan of its own, which had a huge impact: “Gay Is Good!”

Back then, gay was an inclusive term used to denote LGB and T people and this simple three-word slogan was a revolution in queer consciousness in an era when it was deemed outrageous to suggest there was anything good about being LGBT+.

Even liberal-minded heterosexuals often supported us out of sympathy and pity. Many reacted with revulsion and horror when GLF proclaimed: “2-4-6-8! Gay is just as good as straight!”

Those words, which were so empowering to queers everywhere, frightened the life out of smug, arrogant straight people, who had always assumed they were superior.

This challenge to heterosexual dominance and privilege inaugurated a still on-going revolution in laws and cultural values.

It’s a joyous celebration of sexual and gender diversity that contradicted the straight morality that had ruled the world for centuries. The common sense, unquestioned assumption had always been that queers were bad, mad and sad.

All this prejudiced nonsense was turned upside down in 1970, when GLF refused to play by the rules.

GLF overturned the conventional wisdom on matters of sex and human rights.

While politicians, doctors, priests and journalists saw LGBT+ people as a social problem, GLF said the real problem was society’s prejudice. Instead of us having to justify our existence, we forced the LGBT-haters to justify their bigotry.

Like many others of my generation, GLF changed me for the better – and forever.

When I heard about the formation of GLF, I could not wait to get involved. Within five days of my arrival in London from Australia, I was at my first GLF meeting.

A month later, I was helping organise many of its witty, irreverent, defiant protests, as part of the Action Group. Being involved with GLF was a profound personal liberation – arguably the most exciting, influential period of my life.

GLF’s unique style of “protest as performance” was not only incredibly effective, but also a lot of fun. We had a fabulous collection of zany props and costumes, including a whole wardrobe of police uniforms and bishop’s cassocks and mitres, which we used in out street theatre protests.

Imaginative, daring, humorous, stylish and provocative, our demonstrations were both educative and entertaining. We mocked and ridiculed homophobes with wicked satire, which made many of the most hard-faced straight people realise the stupidity of bigotry.

A 12-foot papier-mâché cucumber was delivered to the offices of Pan Books in protest at the publication of Dr David Reuben’s popular sex manual, Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex, which suggested that gay men were obsessed with shoving vegetables up their arses.

Anti-gay Christian morality campaigner Mary Whitehouse had her Festival of Light rally in Central Hall Westminster invaded by a posse of gay nuns.

They proceeded to kiss each other when one of the speakers, Malcolm Muggeridge, disparaged homosexuals, saying: “I just don’t like them.”

The feeling was mutual: we didn’t like him either.

(Peter Tatchell)

On the night of the Miss World contest at the Royal Albert Hall, GLF’s legendary street theatre group staged an alternative pageant on the pavement outside, starring “Miss Used”, “Miss Conceived” and “Miss Represented”, plus a starving “Miss Banglades” and a bloody bandaged “Miss Ulster” — to highlight the then mass hunger in Bangladesh and the war in the north of Ireland.

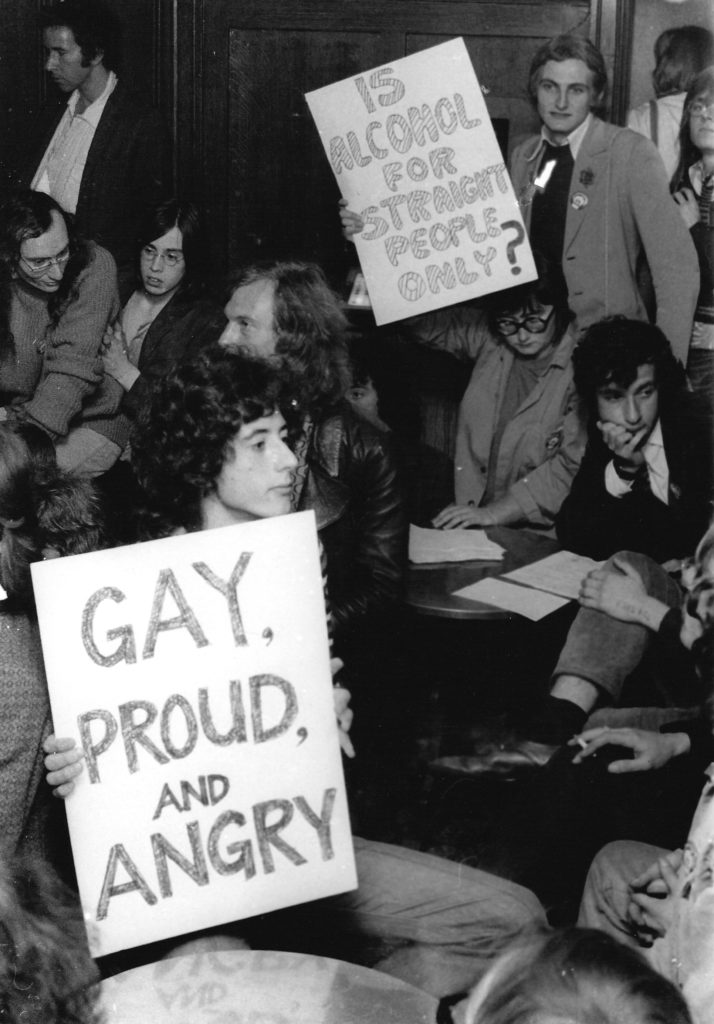

There were also serious acts of civil disobedience to confront the perpetrators of discrimination. We organised freedom rides and sit-ins at pubs that refused to serve “poofs” and “dykes”, forcing them to end their bans.

I disrupted a lecture by the world-famous psychologist, Professor Hans Eysenck, when he justified the use of electric-shock conversion therapy to “cure” homosexuality.

As well as its feisty protests, GLF pioneered many of the LGBT+ community institutions that we now take for granted.

It set up the first helpline run by and for LGBT+ people, which later became LGBT+ Switchboard and the first pro-LGBT+ counselling service, Icebreakers.

Gay News, the UK’s first LGBT+ newspaper, was another GLF creation. These and many other ground-breaking institutions helped shape the LGBT+ community as we know it today, making a huge positive difference to the lives of millions of LGBTs.

Fifty years on, as we look back at the giant strides for freedom that LGBT+ people in the UK have made since 1970, let’s also remember with pride that GLF was where much of it started.