Black queer and trans folk ‘have always been the stewards’ of the liberation movement, even when the world wasn’t ready

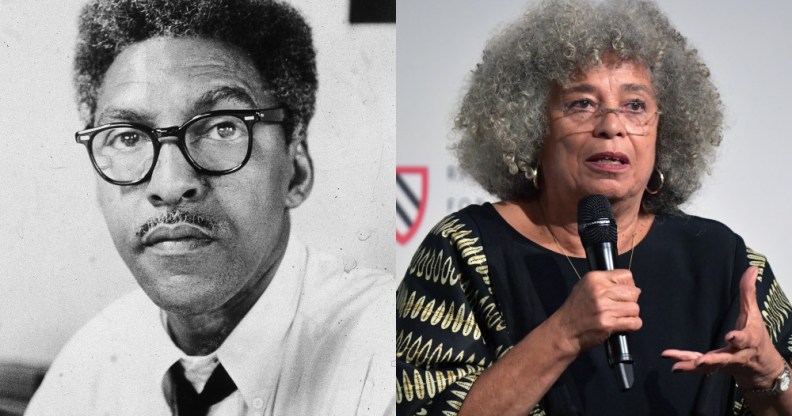

Bayard Rustin was criticised for being gay, while Angela Davis came out publicly in the late ’90s. (Getty)

Queer Black agitators, thinkers and organisers have always been a crucial part of the fight for Black liberation – only now, the rest of the world is catching up.

On May 25, George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. A Black man, father and grandfather, he spent his final eight minutes spent with the knee of a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, pressed against his neck, choking him.

His is a story that bears repeating not just for posterity, but to reiterate the callousness with which Black lives are taken by public servants regularly, and vastly more often than not, with impunity.

The hurt, fear and anger felt by Black people in the months that followed are sadly not new emotions – Black people have been targeted with violence for longer than it bears thinking about. What was new was the platform given to the Black Lives Matter movement in the weeks and months that followed.

An unprecedented wave of protests around the world has brought the issues of systemic racism, white supremacy and police brutality closer to the forefront than they have been arguably at any point this century. There is also a notable, concerted effort to centre queer and trans Black lives, with rallying cries of All Black Lives Matter becoming steadily more common.

Overwhelmingly, these efforts are coming from organisations led by queer and trans Black folk themselves. One example is Black Visions Collective, which is fighting for “a future where all Black people have autonomy, safety is community-led, and we are in the right relationship within our ecosystems”.

As the saying goes, none of us are free until all of us are free. Black Visions Collective works to “uplift and centre Black, queer and trans Minnesotans” specifically, and is a prime example of queer Black folk fighting tirelessly for the community at large. But as Oluchi Omeoga, co-founder and core team member, tells PinkNews, this is nothing new.

“Queer and trans folk, especially queer Black trans folk, have always been the stewards of our movement,” they say.

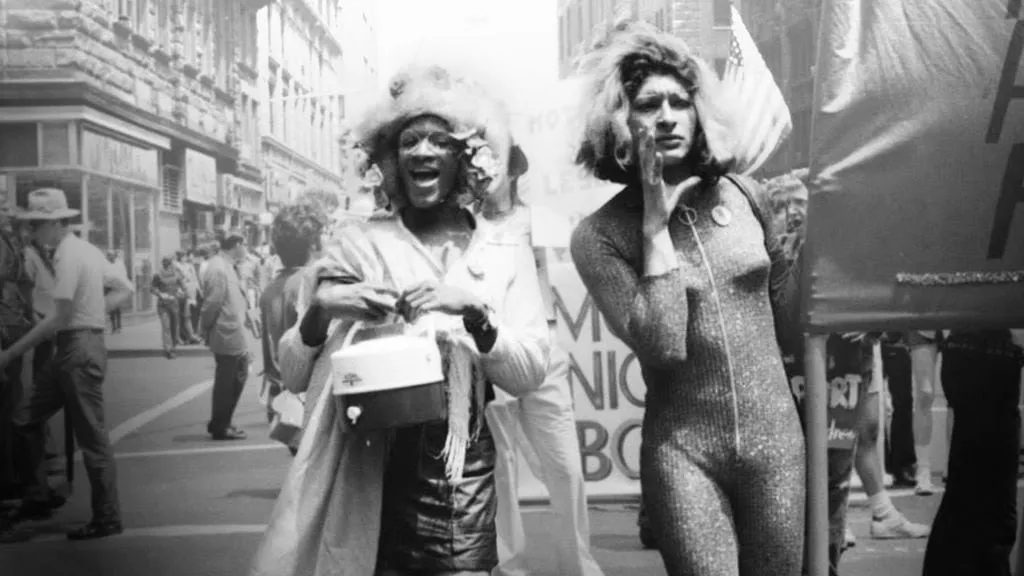

“Look at the history, look at Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, Bayard Rustin, Angela Davis. These folks are and have always had multiple identities… but a lot of the time their identities were erased.

Marsha P Johnson (left) and Sylvia Rivera (right). (Netflix)

“Bayard Rustin was the lead organiser of the March on Washington that got hundreds of thousands of people engaged and was really a pivotal point, or the turning point, of the Civil Rights Movement. It was organised by a Black gay man but he wasn’t able to actually show his identity, because of the time that they were in.”

The difference between them and now, Omeoga says, is that being proudly Black, queer and trans is “more acceptable” for those who aren’t.

“Folk like Raquel Willis, like Munroe Bergdorf, all of these people that have been doing this work, and that have been rooted in this work for very long time, are now being seen as stewards because their identities are ‘more acceptable’. And that’s because of the work that has been going on for years, and years, and years, of letting folk know that we are here and we’re going to get the liberation that we seek.”

PinkNews caught up with Omeoga to find out more about the work that the Black Visions Collective is doing in Minnesota, and what’s important to keep in mind during this ongoing fight.

PinkNews: Can you tell us about some of the things you’re doing right now?

Oluchi Omeoga: We’re really looking at the way in which we see safety, and really agitating and dismantling the systems that make it so that we’re not safe.

Specifically what that looks like, in this time, is really looking at the system of policing and how policing is inherently anti-queer, anti-Black, anti-trans, and asking how do we actually reimagine how we look at community safety so that it centres those who have been most oppressed by the systems that we are working to end?

How do we make sure our calls for liberation don’t become skewed?

Here in this time, because we’re seeing such societal shifts, we’re also seeing capitalism and the other side really kind of shifting the ways that they’re advertising to gain support. So you see places like Target or even PetSmart, all of these places that are now like, ‘We can say Black Lives Matter’. But five years ago, they weren’t saying that.

What we need to do to combat that is really be specific in our asks, and what we’re talking about, and what we’re actually calling for.

So when we say that we’re calling for the end of the brutalisation of Black people, what does that actually mean? That means that we have to end white supremacy, we have to end capitalism. And we have to end gender-based violence and the patriarchy. To be rooted in those three things, then it shapes the way that we’re organising, because now we know that the institution of policing has a direct tie to how we see gender-based violence and the patriarchy. It also has a very specific tie to prisons; we know that prisons are just another form of slave labour in capitalism.

The ways that we can make it so that it doesn’t become a cooptation of the movement is that we actually have to do the analysis. What are the overlapping systems? How are how is this system affected by all of the systems around it? And understanding and knowing that we have to tackle all all of those systems in order to actually gain liberation.

Black LGBT+ lives can often land in the intersections of racism, homophobia, transphobia and misogyny. (Getty/Hollie Adams)

And with that, there’s a need for change in our political systems and our decision-making systems.

Yes, I think that there has to be a huge societal shift in all aspects of what we see in life. I think that for a very long time, even from from ancient times – Hammurabi’s code – you have this idea of retribution, of punishment, an eye for eye.

Really reorienting our society to a lens that lends itself to the humanity of all people is hard to think about in practice. It’s very easy to say conceptually Black Lives Matter, every human life has a value. But then in practice it’s really hard because to do that then you must find humanity in all people, regardless of the decisions that they have made or the choices that led to that decision.

You have to understand that accountability and punishment are two different things. Accountability means that I am accountable for this thing and my humanity is still intact; punishment means that you are accountable to this and because of that, you must give something up to restore or to right the relationship in the world. I don’t think that that’s justice. That’s what we call retributive or punitive justice – it’s not the way I want to see the world. We have to figure out how do we actually hold people accountable, and how do we change the systems that made it so that that person had to make that decision.

If someone steals something because they’re poor and then that person goes to jail, they don’t learn that: ‘Oh, I shouldn’t steal this, because I’m poor.’ What they’re learning is: ‘I have to be sneaky, and, not get caught the next time.’

We have to ask: this person stole something because they’re poor, why are they poor in the first place? And what conditions made it possible for that person to have to make that decision? And how do we change those systems so that that person doesn’t have to make that decision, so that every human being has basic necessities?

Because we’re saying that every human has value. So that value means that they have the opportunity to not just survive in this life, but to actually thrive.

Seeing that humanity is crucial when we talk about things like the epidemic of violence against trans women of colour.

Exactly, when we’re looking at trans violence, a lot of the reasons why trans folks are so oppressed is because they sit at so many different intersections. A lot of folks that are trans are either people of colour, so they see racism in a different light, or they’re low income, and we see how capitalism affects them. We see how gender-based violence in general affects trans folks, trans women especially.

When we’re talking about patriarchy, they feel patriarchy but they also feel trans oppression and transphobia. How do we change that system of patriarchy, that denotes that male-bodied people are inherently worth more than women-bodied people? How do we actually change that? To ask why does this exist and how has it served us in the past, or not served us in the past?

How do we move forward to a vision of actually, every human being has value, regardless of how they identify, or the way that their body came into this world? And giving people the autonomy, of self-identifying and self-actualization, to be able to say I am a trans person, and this is how my brain sees my body. And I’m going to reflect that in how I see my body.

For those of us who do have some form of privilege, but still know a sense of violence and that oppression and want to be more inclusive in the work we’re doing, what would your advice be?

My first advice is when you’re organising, ask who is most at the centre in your organising? Especially with cis gay white men, when you’re working towards dismantling homophobia, what else exists that upholds the system? Well heterosexism also intersects with racism, so who are the people that you’re following or listening to? Who is most of the centre in the organising that you’re doing?

Marsha P Johnson is increasingly celebrated by the entire LGBT+ community, but it wasn’t always that way. (Getty)

Also I think that specifically for folks who are at the margins is the question of how are you talking to other folks at the margins. I see that a lot of cis gay white men are only talking to cis gay white men about cis gay white issues. But how are you actually talking about racism, how are you talking about transphobia in the conversations that you’re having with the people in your specific identity to really dismantle these systems? What is the anti-racist work that you’re doing inside of yourself, of understanding and knowing that you have white privilege? What is the specific anti-patriarchy work that you’re doing, knowing that regardless of your sexual orientation, you still have male privilege? It’s about really doing the work in yourself so that you can do it with those who are around you.

The other thing I think is important is anti-imperialism, especially as Britain owned a large percentage of the world at one point. So what is the work that you’re doing at the same time of understanding the privilege of living in the UK? The UK has had a very strong influence in how the world is shaped today, so how are you undoing imperialist oppression? How are you looking towards what does a global vision of liberation look like, and what do we have to give up in order to gain that that vision?