Remembering the lasting legacy of Harvey Milk 42 years since his death, the gay pioneer who tragically became a martyr

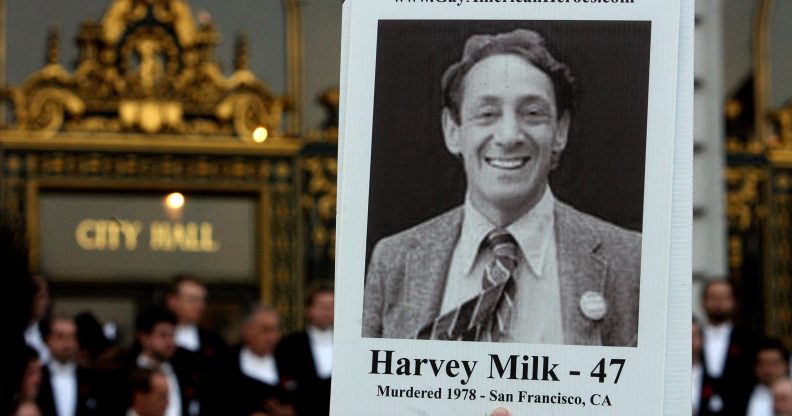

An attendee holds a picture of Harvey Milk at a memorial event marking 30th anniversary of killings of George Moscone and Harvey Milk at City Hall in San Francisco, California. (Mark Constantini/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

Forty-two years ago today (27 November), Harvey Milk was assassinated, and there are many reasons to remember him.

One of which is dog poop.

Decades on since his death in 1978, and San Francisco residents each day peak out of their apartments to see the city’s tanned streets free from pet waste.

They have Milk to thank for this, a city official who sponsored an ordinance that fined people for not clearing up after their dogs.

But there’s more to Milk than a cosmetic improvement to the avenues and roads that criss-cross the city. A pioneer of the LGBT+ rights movement, Milk was the first openly gay man ever elected into public office in the US.

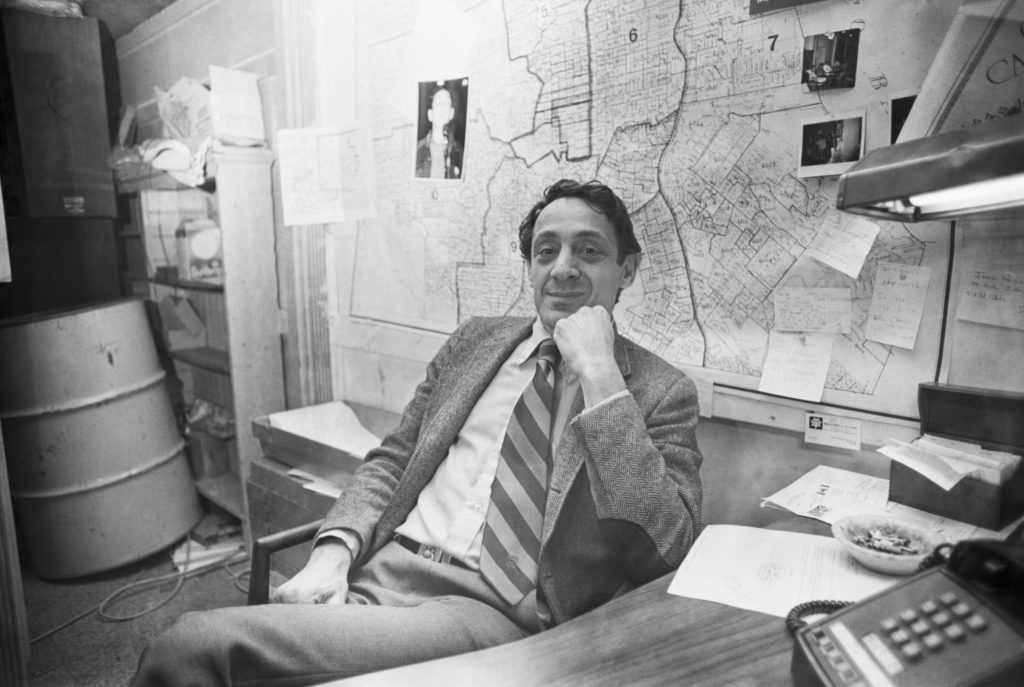

Milk was the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California (Bettman/Getty)

A victory indescribably seismic at a time where fledgeling LGBT+ rights movements were being curtailed by conservative lobbies. Yet Milk managed to galvanise support and, during his time in office, pass a stringent ordinance outlawing discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Less than a year after being elected to the board of supervisors in 1977, he was fatally shot by his former city supervisor opponent, Dan White.

Ever since, his legacy has been celebrated in books, an opera, film, a navy ship in his namesake and even a postage stamp.

Who was Harvey Milk?

Hearts broken. Votes tallied. Lives risked and saved.

The life of Milk that has come to be lauded by his contemporaries is one of a pioneering spirit.

The son of Russian‐Jewish immigrants, Milk, of Long Island, New York, was born in 1930. He went onto earn a bachelor’s degree in 1951 from the Albany State College for Teachers and spent his school years in the closet.

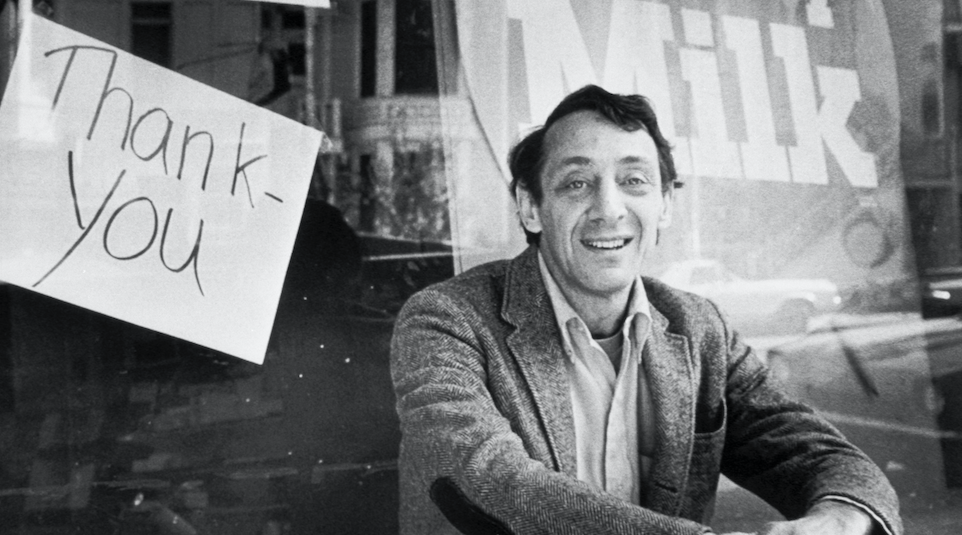

Harvey Milk sits outside his camera shop, November 9, 1977 (Bettmann/Getty)

After graduating, he enlisted in the United States Navy and worked diving instructor in San Diego. Milk served four years before superiors found him in a park with gay men – he was then forced to resign.

His biography then became a brief run-in with Wall Street, but his colleagues noticed his lack of drive for the finance district. Across his forays into local electoral politics, however, everyone could see the passion that fizzled within him.

It took three tries for Harvey Milk to be elected supervisor

Milk was 41 years old with when he crooned into San Fransisco in 1972.

Settling into the Castro district, he set-up a camera shop that became a refuge for the city’s LGBT+ community, long abraded by prejudice. Many looked to Milk for leadership and he exhorted them to be open and visible.

Armed with nothing more than a bullhorn and a dogged, almost impish attitude, he campaigned for city county supervisor in 1973, a move he attributed to anger generated by the televised Senate Watergate hearings.

He was, however, unsuccessful. Losing again in 1975, before beating over 16 other candidates with 30 per cent of the vote in 1977.

Milk won with his multi-pronged policy plan of not only securing LGBT+ rights, but increased low-rent housing, free municipal transportation and better childcare facilities as well.

“It’s not my victory, it’s yours and yours and yours,” he said after winning the historic seat.

Milk’s district, the fifth, encompassed most of the Haight‐Ashbury and Upper Market Street areas, where many queer migrants had decamped. The city was fractured in this way, with neighbourhoods of hippies and working-class Catholics huddling around one another, but Milk found ways to tenderly unite people.

Harvey Milk was slain by his political opponent

On 30 November 1978, a thick fog tangled with the mid-rise buildings of San Francisco for the third consecutive day. But the thousands of people below it didn’t seem to mind.

They stuffed into the Opera House that evening to attend a non‐denominational ceremony. One that many saw the last 10 months as a steady, bleak drumbeat towards.

Three days prior in City Hall, a bullet struck Milk, killing him. Former board member White surrendered to police minutes later.

It was a moment months in the making.

In 1978, Milk struck down Proposition Six, which would have mandated the firing of state public school teachers. White was the sole supervisor who voted against Milk.

Dan White (directly beneath “Fraud” sign). (Getty Images)

After quitting from his post 10 months in, White urged mayor George Moscone to rescind his resignation, citing money troubles. Moscone refused and, on the morning of 27 November, White slung into City Hall through an open window and gunned both Moscone and Milk.

White was subsequently convicted of voluntary manslaughter, rather than of first-degree murder. The verdict sparked the “White Night riots” in San Francisco, and led to the state of California abolishing the diminished capacity criminal defence.

White died by suicide in 1985, a little more than a year after his release from prison.

‘If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country’

Pushing against the cruel, corrosive attitudes of powerful groups that sought to silence and erase LGBT+ people, Milk always knew the punitive reaction to his quest for equality.

Days after his death, Milk’s associates released a tape recording that he had instructed: “Be played only in the event of my death by assassination.”

“I fully realise that a person who stands for what I stand for, an activist, gay activist, becomes a target or the potential target for somebody who is insecure, terrified, afraid, or very disturbed themselves,” Milk said on his final tape.

“I would like to see every gay doctor come out, every gay lawyer, every gay architect come out, stand up and let that world know,” Milk said.

“That would do more to end prejudice overnight than anybody would imagine. I urge them to do that, urge them to come out. Only that way will we start to achieve our rights.”

“If a bullet should enter my brain, let that bullet destroy every closet door in the country.”