Composer Frédéric Chopin wrote homoerotic love letters that were ‘deliberately erased from history’

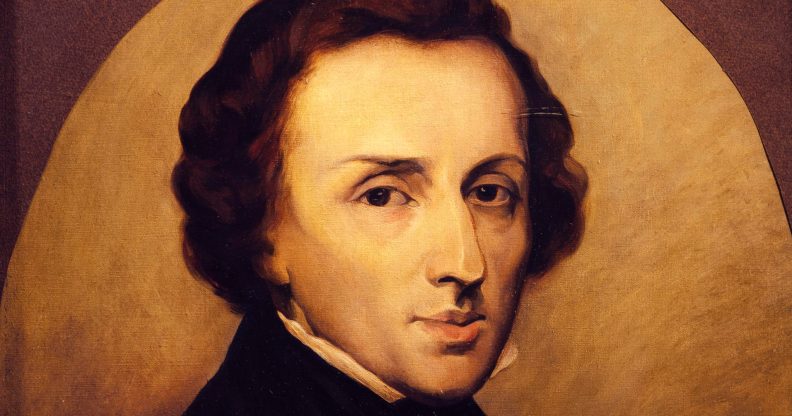

Portrait of Frederic Chopin by Zelazowa Wola, 1849.(DeAgostini/Getty)

Gay love letters written by Polish composer Frédéric Chopin were deliberately mistranslated by historians to conceal his sexuality, a music journalist has claimed.

According to The Guardian, Swiss music journalist Moritz Weber had been researching letters written by Chopin during lockdown earlier this year when he discovered a “flood of declarations of love aimed at men”.

His findings were explored in the two-hour radio show Chopin’s Men, aired on the arts channel of Swiss broadcaster SRF, and Weber insisted that some of the composer’s writing must have been intentionally mistranslated.

In one letter, Chopin said that rumours about his love affairs were a “cloak for hidden feelings”, and his writing also hints at an interest in “cottaging”, or looking for sex in public toilets.

In one letter to a male school friend, he wrote: “You don’t like being kissed. Please allow me to do so today. You have to pay for the dirty dream I had about you last night.”

There are 22 letters on record from Chopin to the same friend, Tytus Woyciechowski, and he often began them with “my dearest life”, and signed off: “Give me a kiss, dearest lover.”

But the English-Canadian biographer Alan Walker insisted in his 2018 book Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times that the homoerotic love letters penned by Chopin were the result of “psychological confusion”, and added that Woyciechowski was a “bosom friend”.

Chopin gay love letter was edited to suggest it was about a woman.

In an 1829 letter to Woyciechowski, Chopin wrote: “My ideal, whom I faithfully serve, […] about whom I dream.”

However a translation of the letters published by the Fryderyk Chopin Institute in Warsaw, Poland, described his “ideal” as a woman, despite the original letter using the masculine version of the Polish noun.

A spokesperson from the institute spoke on the radio show, and admitted that there was no actual proof that Chopin had had relationships with women, only rumours and accounts from family members.

The translator of the 1829 letter told The Guardian: “He was a romantic who definitely didn’t discriminate between men and women in his expressions of ‘love’. But to say that there is some sort of conspiracy behind ‘missing’ letters in the various critical editions is absurd.

“The institute is indeed a politically conservative organisation, but I didn’t find any bowdlerisation in the Polish edition, nor any ‘correction’ of my notes to passages where Chopin’s sexuality was concerned.”

Whether or not the editing of Chopin’s love life was intentional, Weber said he hopes that shining a light on his sexuality will help people better understand his music.

In a letter Woyciechowski, Chopin wrote: “I confide in the piano the things that I sometimes want to say to you.”

Weber added: “The fact that Chopin had to hide part of his identity for a long time, as he himself writes in his letters, would have left a mark on his personality and his art.

“Music allowed him to express himself fully, because piano music has the advantage of not containing any words.”