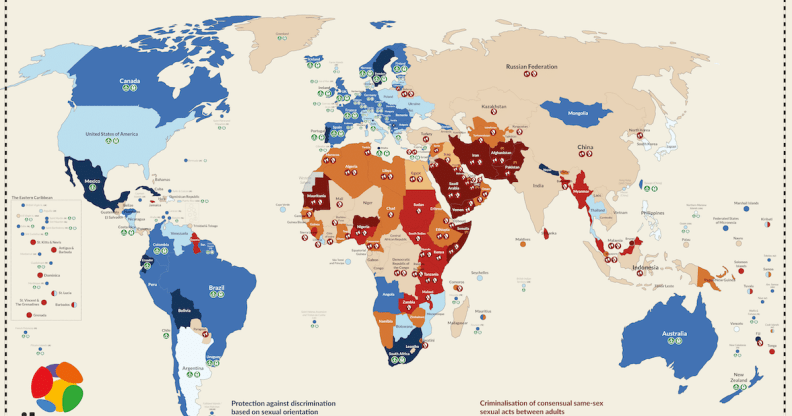

The dangerous and oppressive countries where same-sex love is still a crime, mapped

A new report from ILGA World has revealed that same-sex sexual activity is still illegal in 69 UN member states (Image courtesy of ILGA-World)

Being gay, lesbian or bisexual is still a crime in 69 United Nations member states, a new report has revealed.

There have been significant advancements on LGBT+ rights in many countries across the world over the last two decades – but progress in some territories has proven slow, with same-sex relations still criminalised in some locations.

A new report from ILGA World (the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association) has found that same-sex sexual relations are still criminalised in 69 United Nations member states in 2020.

The figure is a drop of just one from 2019, suggesting that progress on LGBT+ rights in many countries is stalling.

At least 34 of those states have actively enforced their anti-homosexuality laws in the last five years, according to the report, published on Tuesday (15 December) – however, the real number could be “much higher”.

The death penalty remains in place for queer people in six UN member-states, including Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria (homosexuality is punishable by death in 12 northern states), Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

The death penalty could also be imposed in five other UN member states – Afghanistan, Pakistan, Qatar, Somalia and the United Arab Emirates – but there is less legal certainty, ILGA said.

Additionally, 42 UN member states have legal barriers to freedom of expression on sexual orientation and gender identity, while 51 states prohibit people from forming NGOs dedicated to the LGBT+ community.

Gay and bisexual people face arrest ‘at any time’ in 69 United Nations member states

“As of December 2020, 69 states continue to criminals same-sex consensual activity,” said Lucas Ramón Mendos, a research coordinator at ILGA World and lead author of the report.

“The figure dropped by one this year, as Gabon backtracked from the criminalising provision it passed in 2019 – which became the shortest-lived law of its kind in modern history.

“Moreover, last week Bhutan’s parliament approved a bill to decriminalise consensual same-sex relations, and may soon be signed into law,” he added.

Mendos said that people in these countries may end up being “reported and arrested at any time” on suspicion of same-sex sexual activity, and some territories punish queer people with “jail, public flogging, or even death”.

The report also highlighted some positive changes over the last year. In July 2020, Sudan repealed the death penalty on same-sex sexual activity, while same-sex marriage is now legal in 28 UN member states since Costa Rica extended legal recognition to queer couples, making it the first Central American country to do so.

Meanwhile, Monaco and Montenegro legalised civil partnerships over the last 12 months, meaning 34 UN member states now offer some form of legal recognition for same-sex couples.

The rights of LGBT+ people in the workplace also continue to improve, with 81 UN member states implementing laws prohibiting discrimination in the workplace based on sexual orientation. Just 15 countries offered legal protection for LGBT+ people in the workplace 20 years ago.

The report also praised Germany for implementing a nationwide ban on conversion therapy, meaning that four UN member states now have outright, national bans on the traumatising practice.

Five other UN member states – Australia, Canada, Mexico, Spain and the United States – have “subnational bans”, meaning the practice is prohibited in some territories.

Explicit legal protections against violence and discrimination have become – more than ever – paramount to safeguard our human rights and dignity.

Julia Ehrt, director of programmes at ILGA, addressed the challenges facing LGBT+ people across the world in 2020 as the coronavirus pandemic plunged communities into uncertainty.

“Many were left struggling to survive in a world that has become even more unequal and violent,” Ehrt said.

“For our communities, safe spaces dramatically shrunk overnight. Some governments took advantage of these circumstances and stepped up their efforts to oppress, persecute, scapegoat, and to violently discriminate against us.

“In many places were laws were already a cause of inequality, things have only got worse.”

Ehrt added: “Amidst such concerning situations, explicit legal protections against violence and discrimination have become – more than ever – paramount to safeguard our human rights and dignity, to prevent harm, and to heal from the violations we suffer.”