Why we should all be more like legendary lesbian football player and all-round badass Lily Parr

Lily Parr (b. 1905) was a well-known lesbian footballer who lived her life proudly and freely. (Getty/Creative Commons)

LGBT+ History Month is all about remembering our forefathers, foremothers and forepeople who paved the way for the rest of us, and there are few UK figures who are more trailblazing than chain-smoking lesbian footballer Lily Parr.

Lily Parr was born in 1905 in a small rented house in St Helens, Merseyside: one of seven children, and grew to be a striking, tall girl with jet black hair and an athletic frame. She was well known for her large appetite, her heavy drinking and love of high tar Woodbine cigarettes – known as ‘gaspers’ because of the effect they had on first time smokers’ lungs.

As a kid, she spent her spare time playing football on a stretch of waste ground, honing her skills.

As writer Barbara Jacobs points out in The Dick, Kerr’s Ladies: “She (Lily Parr) was as adept at rugby as she was at football, spending hours on her own perfecting the technique of the power kick. She’d sorted that out by the time she was thirteen and in football could score from any place on the pitch, or in rugby kick the finest penalty or drop goal. A left-footer, her ability was natural, magic, but honed by her refusal to conform to the art of being a woman. She wasn’t having any of it.”

Dick, Kerr Ladies F.C. in 1921 (Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

In 1919, she began playing for St Helens Ladies and caught the eye of the manager of the Preston factory team Dick Kerr Ladies. He offered her and her team-mate Alice Woods a job in the factory and a spot on the team, and they agreed.

The Dick, Kerr & Co factory in Preston had taken on a score of women employees in 1914 to help produce ammunition for the First World War, and football was encourage to maintain morale amongst the female staff. After a group of women beat a group of male apprentices during an informal lunchtime game, Dick, Kerr Ladies F.C. was formed, and went on to make history. They were the first women’s team to wear shorts, tour the continent and the US, and raised money for charity too.

In her first year with the club, Parr scored a whopping 108 goals. The Dick, Kerr’s Ladies F.C. drew big crowds from the get go, in fact when they beat Arundel Coulthard Factory 4–0 on Christmas Day 1917, they did so in front of a crowd of 10,000 people.

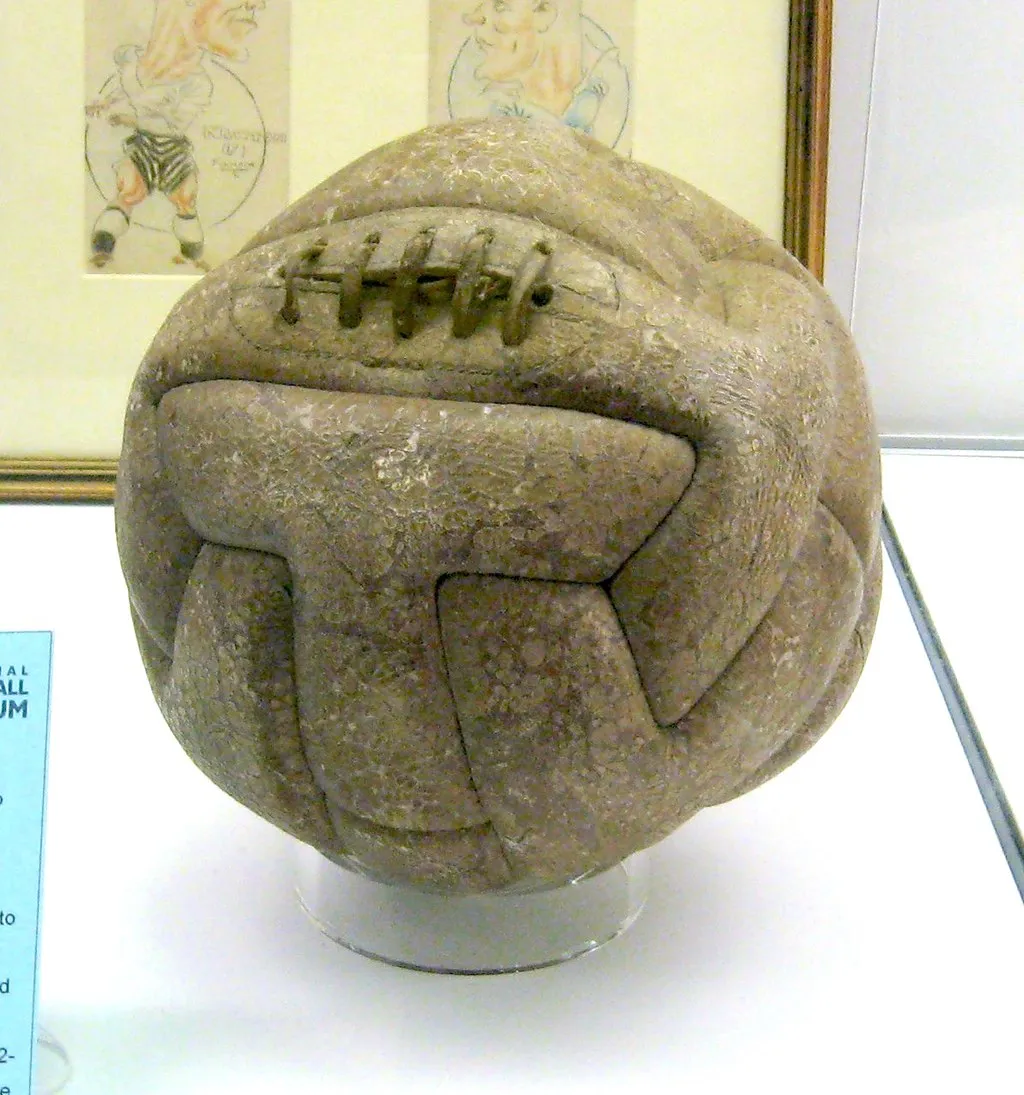

The heavy leather football used in the 1930 World Cup Final (Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

By all accounts, Parr was in her element, with a reputation for being a fierce, formidable opponent. After scoring a penalty against a male goalkeeper who mocked her, saying she couldn’t score past him, he exclaimed: “Get me to the hospital as quick as you can, she’s gone and broken me flamin’ arm!”

Back then, footballs weren’t the relatively lightweight globes they are these days. One of Parr’s teammates would later write: “She was the only person I knew who could lift a dead ball, the old heavy leather ball, from the left wing over to me on the right and nearly knock me out with the force of the shot…”

The popularity of women’s football – and Dick, Kerr’s Ladies F.C. continued to grow. On Boxing Day of 1920, they played a match against St. Helen’s Ladies at Goodison Park in Liverpool that drew a crowd of 53,000 spectators, a record attendance for women’s club matches that lasted for 98 years.

Unfortunately, this success drew the attention of, yes, you guessed it: the patriarchy.

Less than a year later, Dick, Kerr’s Ladies and all other women’s teams lost their official recognition by the FA, who banned them from playing at FA grounds. The wording of the ban is about as infuriating as you might expect:

“Complaints having been made as to football being played by women, Council felt impelled to express the strong opinion that the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and should not be encouraged.

“Complaints have also been made as to the conditions under which some of the matches have been arranged and played, and the appropriation of receipts to other than charitable objects. The Council are further of the opinion that an excessive proportion of the receipts are absorbed in expenses and an inadequate percentage devoted to charitable objects.

“For these reasons the Council requests the Clubs belonging to the Association refuse the use of their grounds for such matches.”

Two team captains greet each other with a kiss. England, Preston, 1920 (Wikimedia/ Creative Commons)

The ban stayed in place until 1971, but didn’t stop Lily Parr continuing to play football, or living her life to the full.

Records seem to show that Parr did whatever she wanted off the pitch as well. Openly lesbian, she lived with her partner Mary.

After the Dick Kerr factory was taken over by new company English Electric, many women lost their jobs. However, the team continued, rebranded as the Preston Ladies. And as the team had raised a lot of money for Whittingham Hospital and Lunatic Asylum, many unemployed members were offered jobs there. Parr retrained as a nurse, and it was there she met Mary, one of her co-workers. They fell in love and didn’t hide the fact they were an item, in fact they even bought a house together.

Parr continued to work at the hospital, eventually rising to the rank of Ward Sister. She also continued to play for the Preston Ladies until the age of 45. In 1946, she was named captain. In 1950, she scored in an 11-1 victory over Scotland.

The heavy hobnail boots she wore that day are now displayed at the National Football Museum, still caked in mud. She died from breast cancer in 1978, aged 73, 7 years after the FA ban was lifted.

In 2002, she became the first and only women to enter the Football Hall of Fame. So, this LGBT+ History Month, let’s all pause and take a moment to remember her life and her incredible achievements. Maybe we should all try to be more like her in 2021 (apart from the heavy smoking, that is).