How an incredible treasure trove of letters shone a light on the secret life of 1950s drag queens

A drag queen puts on earrings in PS Burn This Letter Please. (Provided)

In 2014, a box stuffed full of letters was discovered languishing in a Los Angeles storage unit.

The letters, addressed to Reno Martin, were written by a group of drag queens who lived, loved and served looks in 1950s New York City. Just like that, the letters brought to life a hidden queer history full of joy, passion, scandal and heartache.

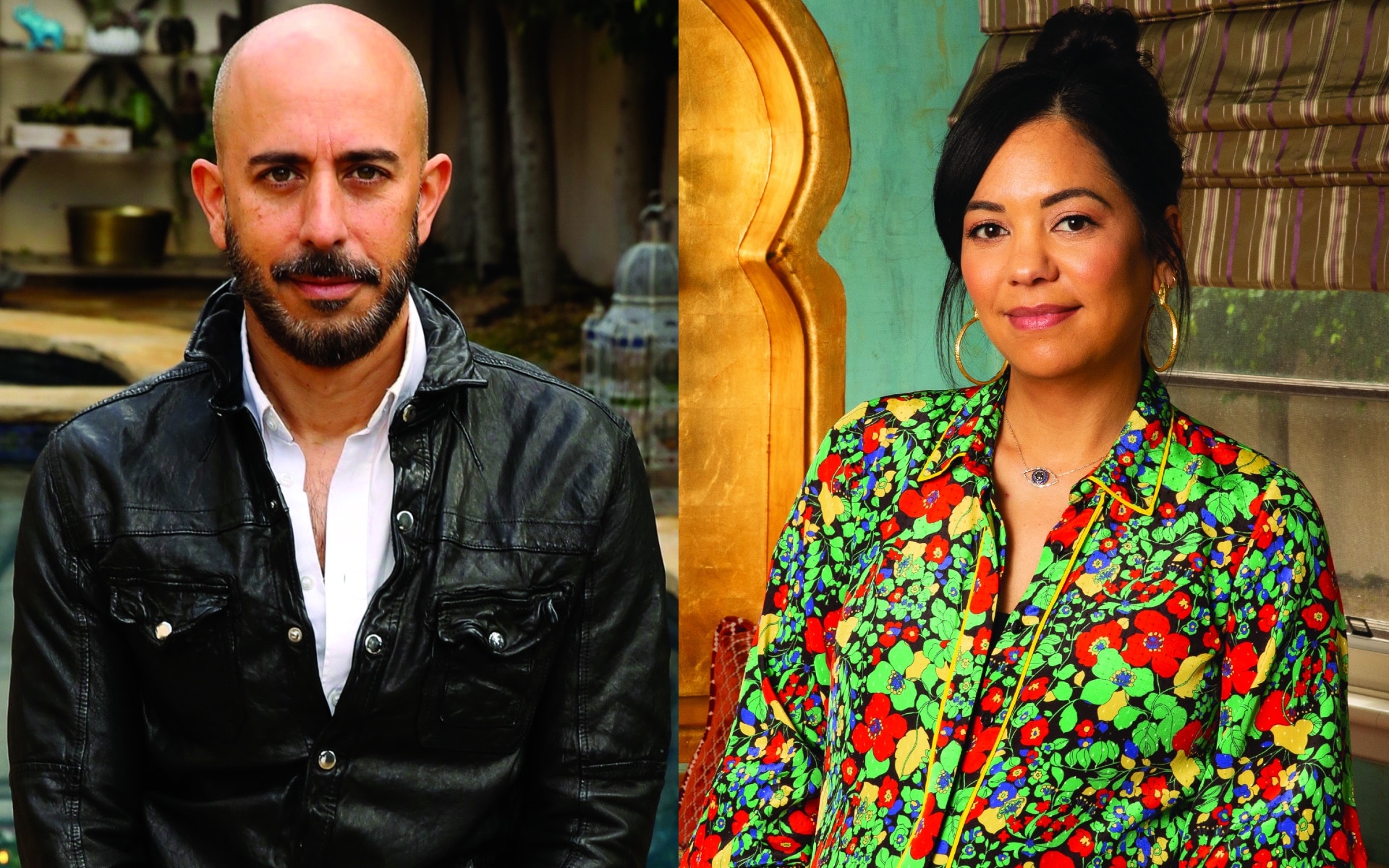

Those letters form the basis of PS Burn This Letter Please, a documentary that gives an incredibly rare personal look into the drag culture of a bygone era. Over the course of more than five years, directors Michael Seligman and Jennifer Tiexiera tracked down the surviving writers of the letters – as well as reams of moving archival footage – to bring hidden queer histories to the fore.

The box of letters was first discovered following the death of American talent agent Ed Limato, who used the name Reno Martin as a nom-de-plume during his stint as a disc jockey. After leaving New York City, he kept in touch with his drag queen friends through letters. He kept those correspondences for his entire life, neatly stowed away, just waiting to be uncovered.

Seligman knew right away that the letters were a treasure trove that could help breathe new life into a forgotten era of queer history. The challenge, of course, lay in tracking down the queens who populated New York’s drag scene in the 1950s.

“These guys were writing these letters in secret, often using their drag names instead of their real names, so if the letters were discovered, nobody would know it was them,” Seligman says.

“It took us a while to convince the people to actually sit down and talk to us. Even though this was 60 odd years ago, for a lot of them, it was still a very private and personal part of their life that they hadn’t really spoken about.”

Two years in, Tiexiera joined the project, excited to bring to life a subculture that had gone “totally unexplored”.

“A lot of these people, because they’re all in their 80s and 90s, a lot of them don’t have email – they have landlines. And so that was new for us. We were just constantly calling these landlines and then we would get a bite,” she explains.

Seligman and Tiexiera were eager to interview the surviving drag queens – or female impersonators, as many preferred to call themselves – on camera. However, building trust took time. The older queer people featured in PS Burn This Letter Please were often keenly aware of the stigma and discrimination that could follow them if they went public with their stories of New York’s 1950s drag scene. All but one of the queens interviewed in the documentary had “a lot of reservations”, Tiexiera says. In the end, she and Seligman flew across the country, meeting with the queens in an effort to build relationships and foster meaningful connections before doing sit-down interviews.

Both directors were determined to bring the drag queens’ stories into the open in an effort to subvert stereotypical assumptions about queer life pre-Stonewall in America.

PS Burn This Letter Please dispels myths about queer life pre-Stonewall

“I think we have a sense of what gay history was, or what gay people were like, prior to Stonewall,” Seligman says. “There are these myths that everybody was ashamed and in the closet and an alcoholic, and all of these terrible things. And then you meet these people and they’re so grounded, they’re so well-adjusted. They know who they are and they’re also very aware of the world that they live in.”

He continues: “They were taking their lives in their hands on the regular back in the 1950s. But now they’re living in small towns – some of them have gone back to where they came from – and they realise, ‘If somebody recognises me, there could be some kind of queer backlash, some kind of hate crime perpetrated.’ These people are old – a lot of them live by themselves, and they were sort of protective.”

I can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday, and they’re remembering things in such specific detail that happened 60 odd years ago.

Once Seligman and Tiexiera broke through those barriers of stigma and fear of discrimination, they found a group of queer elders excited to share memories and stories of their wild and wonderful lives.

“Their memories are beyond,” Seligman says. “I can’t remember what I had for lunch yesterday, and they’re remembering things in such specific detail that happened 60 odd years ago.”

Doing the interviews was an incredibly emotional experience for both Seligman and Tiexiera. Both directors are moved to tears when reflecting on the amazing, empowering, and sometimes heartbreaking stories queer elders told them. One such moment came when Terry – a trans woman and former drag queen – told them about the love of her life, Nicholas Dante, an acclaimed dancer and writer best remembered for having co-written the book of The Chorus Line.

Terry had “a really hard time” when she first came on the drag scene in the 1950s, Tiexiera says.

“Two people were nice to her, and he was one of them. She’s had all these beautiful fond memories, and then she gets to the point where she tells about him passing away during the AIDS pandemic, and she can barely speak. And I just remember looking at Michael, we’re both covered in tears, because not having lived through that, or being very young when that was happening, it was more like a news story. And just to see the serious personal connections – it was all pretty hard hitting.”

Seligman found himself laughing and crying through every interview they did, and was often amazed by the unique ways each of the queer elders told their stories.

“I think what was really special was this knowledge that we were rescuing this aspect of queer history at the last possible moment. It’s a miracle that these people have lived as long as they’ve lived, and to be able to sit with them and capture all of this stuff, and ensure that future generations of queer people and future generations of drag queens will have a record of the people that came before, of who took the knocks, who got arrested, who got beat up, and who spent nights in jail.”

Seligman – who also works as a producer on RuPaul’s Drag Race – was amazed by the links between drag culture in the 1950s and today. The trove of letters showed the ways in which slang is passed down from generation to generation, providing vital ways for queer people and drag queens to communicate with each other.

“It’s such a very niche culture. I mean, it’s becoming much more mainstream, and we’re all getting a window into that drag world through TV,” he says. “But what’s really fascinating to me is when reading these letters, they say things like ‘mopping’, which means shoplifting. The fact that drag queens today are using that same phrase, in that same way, to mean shoplifting is really kind of remarkable.

“The fact that this history, without ever being written down, has been passed on from drag mother to drag daughter for decades is really interesting,” he says. “And one thing a lot of the queens said, which I get choked up saying, when I asked them, ‘What do you think about drag today versus the 1950s?’ They would be like, ‘Well, if you told us in the 1950s that there would be drag queens on television some day, we wouldn’t have believed you.'”

The mafia got involved in the drag scene to make money

In making their documentary, Seligman and Tiexiera also uncovered some fascinating – and surprising – facts about New York’s drag culture in the 1950s. Perhaps the most surprising revelation in PS Burn This Letter Please is the mafia’s involvement in the drag scene.

In making the documentary, Seligman and Tiexiera discovered that 82 Club – a popular New York drag bar that largely catered for straight people – was actually run by the mafia.

“I don’t know that the mob necessarily had any soft feelings for gay people, but they certainly saw it as a way to make money,” Seligman says. “And over time, certainly, there were these relationships that grew up.”

During their interviews, Seligman and Tiexiera discovered that Anna Genovese – the wife of mobster Vito Genovese – actually helped pay for Terry’s transition.

It’s not all dark. It’s actually a lot of sequins and glitter.

“I think it was just a really symbiotic relationship,” Seligman says. “The mob saw it as a way to make money. The queens made money, and they were also offered a lot of protection. If they were being harassed outside of the club, in or out of drag, all they had to do was drop that name Genovese and nobody’s going to mess with you.”

The finding points to an indisputable fact: queer life in the 1950s, much like today, was complex and often surprising. There is no single story, no simplistic version of events. New York’s drag queens lived full, vibrant lives – even if mainstream society wasn’t prepared to accept them.

Seligman and Tiexiera made a conscious choice in making PS Burn This Letter Please that they wanted to represent those complexities. Up until now, historians studying the lives of queer people have had to rely on court, police and hospital records to construct a version of events. The discovery of Limato’s letters meant that they could move away from that detached reading of the past, instead bringing real people’s stories to life.

“I know it’s a cliché, but it’s just so about them,” Tiexiera says. “I have never been so attached to my participants in a film ever. I just love them with all my heart. They’re extraordinary. And the fact that they were brave enough to do this, I think it’s just a gift to all of us. We have these letters talking about love and romance and dresses and so much fun stuff. We definitely tried to focus the film in that direction and made all those decisions in the edit room very deliberately.

“It’s not all dark. It’s actually a lot of sequins and glitter,” Tiexiera says.

PS Burn This Letter Please was streamed as part of BFI Flare, London’s LGBT+ film festival. It is available to stream on Discovery+ from 1 June.