The extraordinary story of how poppers became a cornerstone of gay culture

Poppers! (PinkNews)

For some, they’re part of a good night out. For others, they make sex more sensual, more free.

Some people prefer to sniff poppers at home by themselves, where they can reach a high and climax in solitude. They mean different things to different people, but within the queer community, poppers are most often seen as a source of pleasure.

They are such a major part of queer culture today that it’s easy to forget that there’s a long, fascinating history behind those little bottles. This remarkable story is told in Deep Sniff: A History of Poppers and Queer Futures by Adam Zmith.

According to Zmith, it’s “impossible to pinpoint exactly when amyl nitrite became a recreational drug” – but research indicates that queer men started using them to relax their sphincters in the 1960s.

The first use of amyl nitrite was documented in the 1840s by a man called Antoine Jérome Balard, but it was really the Scottish scientist Thomas Lauder Brunton who brought the substance to life.

Brunton started using amyl nitrite to treat patients with angina, believing that it could help to lower their blood pressure. This ultimately led to amyl nitrite being sold in glass ampoules on a prescription basis. Patients were instructed to crush them and inhale the fumes. It was the popping sound those ampoules made when they were crushed that gave rise to the slang term “poppers”.

By the start of the 60s, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States decided that amyl nitrite was tame enough that a prescription was no longer required. But by the end of the decade, following reports that young, healthy men were misusing the substance, the requirement for a prescription was reintroduced.

But it was far too late – the horse had well and truly bolted, and poppers had become firmly embedded within queer cultures.

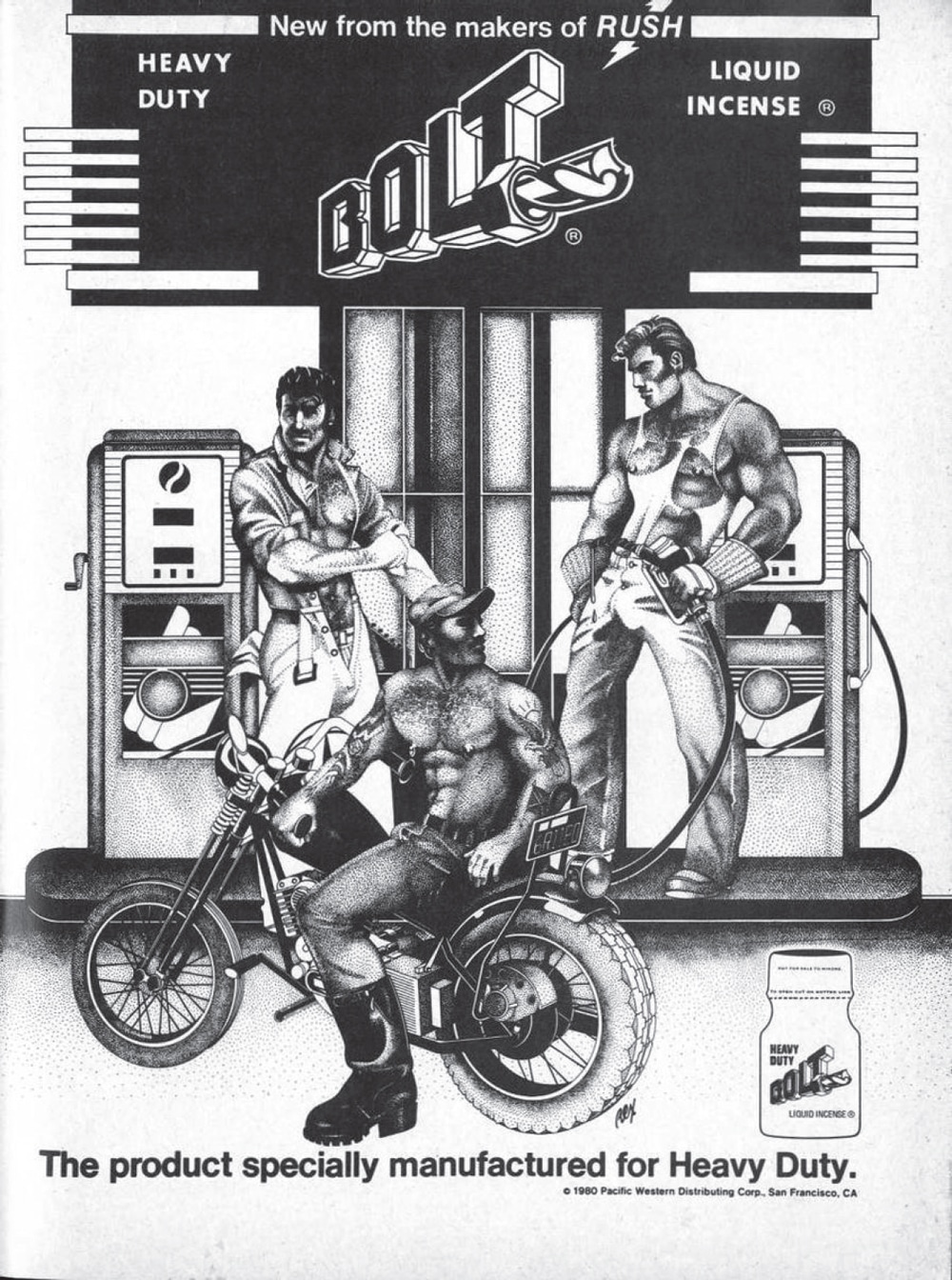

It was after the FDA reintroduced its prescription requirement that capitalism swooped in to save the day. Recognising that there was demand, entrepreneurs started modifying amyl nitrite slightly so they could sell it legally in small bottles designed for sniffing. In a bid to appeal to the gay community, manufacturers started marketing their products with pictures of hulking, muscular men riding motorbikes and dressed in leather.

People thought poppers were causing AIDS in the early days of the epidemic

In his book, Zmith charts the fascinating evolution of amyl nitrite – but he does so much more than just providing a simple history. Deep Sniff: A History of Poppers and Queer Futures explores how and why poppers have become so synonymous with queer men. It also explores how poppers fitted in with the moral panic of the AIDS epidemic – and he brings readers up to the present day, where poppers are increasingly the subject of government scrutiny.

In the early 1980s, a significant number of gay and bisexual men started presenting at hospitals with serious, life-threatening diseases.

Before researchers identified that those men were infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, there was a period in which everybody was searching for answers. Poppers got caught up in the search for a solution.

The scientists researching the disease began to notice that many of the men dying from AIDS had used poppers at one point or another. Increasingly, people began to wonder if the small bottles that had brought so much pleasure to queer men’s lives were actually causing incurable diseases.

What followed was something of a moral panic – although it wasn’t entirely unjustified. People wanted to know what they could do to protect themselves. Pinning the blame on poppers was a simple, albeit understandable, solution.

The panic continued to thrive even long after researchers identified HIV as the cause for AIDS. In 1986, London police famously raided the Royal Vauxhall Tavern – a popular gay bar – and seized boxes of poppers. Zmith is too young to remember the early days of the AIDS epidemic, but he says the hysteria surrounding poppers in those days did lasting damage to the image of amyl nitrite.

“If I speak to people who are at least in their 50s who remember being a part of gay sexual life in the ‘80s, they definitely say that poppers were a part of the justified panic over what was going on,” Zmith tells PinkNews.

“Understandably, lots of people were looking for a cause, and even when we knew it was a virus, lots of people were looking for co-factors – things that would, for example, make you more or less likely to become infected with the virus. Because there were heavy correlations between the amount of sex you were having, the amount of poppers you had, and therefore your likelihood to become infected with HIV.

“There was this panic about all of that, so for a lot of people, they just said: ‘I’m going to cut out this and this, because those things, at the minimum, they’re correlated, and at the most, they might be implicated.'”

That era “really did harm the standing of poppers”, he says. The panic was justified at the start – but some groups, including gay people, persisted in their anti-poppers campaign even after scientists came to understand how HIV was being spread.

“There were some people that persisted in blaming poppers, and that probably is just their own prejudice at that point because they’re not following the science,” Zmith says.

Censorship online has driven ‘popperbators’ to the edges of the internet

Today, scientists have a much greater understanding of HIV and AIDS. As the years subsided, poppers stopped being linked with HIV transmission in the same way. The culture around amyl nitrite also changed with the dawn of the internet. In his book, Zmith delves into his own experience of “popperbator” online culture, which sees people using poppers while masturbating.

The internet is full of popperbator videos, which are often compilation videos made up of porn clips. At various instances, the video will instruct its viewer to sniff poppers. According to one popular popperbator website: “The purpose of this kind of porn is to help us fully enjoy the effects of poppers and thus reach Nirvana alone or with other people. You’re not only a spectator of our porn and fantasies but you become an active participant.”

Zmith first stumbled upon the world of popperbating by accident, he says. “I probably came into the world of popperbating just because of the algorithms of porn websites that gradually managed to filter out the things that you’re not interested in and filter in the things that it thinks you are. I think I must have come across those videos, which is interesting, because I might not come across them now because they are largely removed from the main porn websites like PornHub.”

View this post on Instagram

These videos are being censored because many of the big porn websites have “narrowed down” the types of content they carry, Zmith says.

“Of course, as a company, they’re allowed to do that – they can do anything they want, they don’t have to put anything on their platform. I don’t think this is really a matter of free speech. So any platform can include or exclude anything it wants. But I think they’re narrowing down those choices because of the pressure from the payment processing companies that don’t want to be associated with all sorts of sex work, and also from public pressure and loud voices in the media that are basically moralising against porn as a category, or specific types of porn.”

Some of the biggest porn websites now only allow uploads from porn studios, meaning popperbator videos – which generally infringe upon copyright to begin with – can no longer be disseminated in the same way. There has been a good side to all of this – the policy means that videos depicting sexual assault and child abuse are no longer as easily uploaded to big porn websites. But it has also popperbators to the fringes of the internet.

“I think the impact of this on popperbator culture is that it is not as open and not as visible and not as present as it was a few years ago,” Zmith says. “And so, as ever, it drives people into smaller and smaller communities with extra levels of stealth. And so, whenever that happens, for some people there is shame attached, and it can bring up shame for people when they feel that they have to go further and be more secretive about getting the content they want to get and exploring the sex imagination that they have.”

Despite this increasing move towards censorship, Zmith doesn’t believe there’s significant shame or stigma attached to using poppers today – or at least, the shame isn’t specific to poppers.

“I haven’t detected shame to do with poppers. I think that if there is a shame about it, and this is probably the reason why it’s still quite stealthy, is because it’s attached to sex. I think people are less likely to talk about sex and people are more likely to have shame about sex than they are about sniffing a drug – especially because this is bum sex. And it’s not just bum sex, actually, it’s sex for pleasure’s sake, because poppers give you pleasure and they facilitate further, deeper pleasure. I think some people are ashamed of talking about sex for pleasure’s sake because we’re all supposed to just get married and stop having sex!”

Adam Zmith expects governments will keep trying to outlaw poppers

Zmith’s remarkable book brings readers right up to the present day, to a world where poppers are often the subject of government scrutiny. For example, poppers are currently illegal in Canada (they were banned in 2013) and the UK government floated the idea of banning them in 2016. The very suggestion led Tory MP Crispin Blunt to stand up in parliament and tell his colleagues that he is a proud poppers user.

Zmith doesn’t expect efforts to criminalise poppers to end anytime soon. In fact, he thinks it’s a conversation that will inevitably keep coming back around.

“There will continue to be a bungee jump of politics and policy to do with poppers,” Zmith says. “Control of poppers is often correlated with high-profile cases of misuse or death, which is the same with every drug and any substance and any thing that people do, basically. If there’s a high-profile death or misuse then lots of people say, ‘Let’s reconsider this, should we ban this? Should we control it more?’ And I think that’s probably what happened in Canada in 2013. There’s an inevitable bungee jump about that, back and forth.”

Aside from those high-profile cases of misuse, poppers tend to avoid public attention. In his book, Zmith delves into the ways in which poppers have become “ubiquitous” within certain communities, yet somehow remain “invisible”.

“That to me is one of the great survival tactics of poppers as a substance – it’s that they’re everywhere and if you know, then you know, and if you know what they are, then you know. And yet, they mostly evade attention.

“So yes, there will be these bungee moments, back and forth, but for the most part, they’re quite stealthy – and I think that’s part of the attraction to queer people.”

Deep Sniff: A History of Poppers and Queer Futures by Adam Zmith is published by Repeater Books.