Meet the 19th century trailblazer who fought for gay rights before the word homosexual even existed

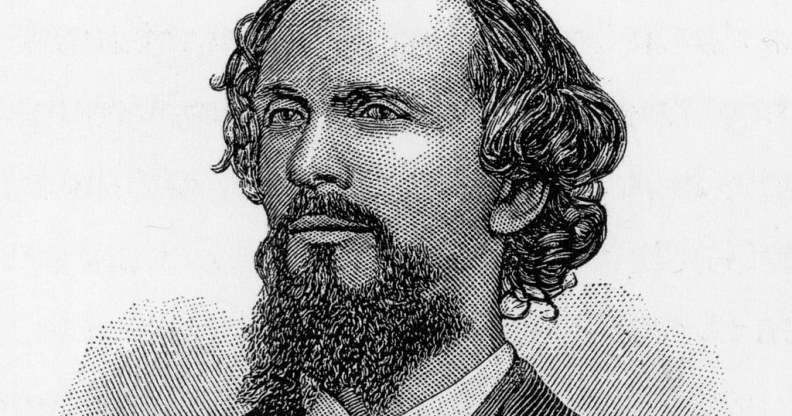

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs.

On 29 August 1867, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs stood up in the Congress of German Jurists and passionately called for anti-gay laws to be repealed.

It was a momentous occasion in the worldwide history of LGBT+ rights – but it was also significant for another reason, as it became the first public coming out on record.

That incredible moment was just one chapter in Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’ long battle to win recognition for people who found themselves sexually attracted to the same gender.

Throughout his life, Ulrichs fought tirelessly to improve the standing of gay, lesbian and bisexual people in a hostile society. Fundamentally, he believed that sexual orientation was innate – a groundbreaking notion during his lifetime – and he wrote extensively about his ideas.

On National Coming Out Day, we remember the life and legacy of Ulrichs – a man who shocked society with his trailblazing efforts to normalise queerness during a time when LGBT+ identities were neither understood nor accepted.

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs invented his own terms to describe queer people

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs was born in Aurich, north-west Germany, on 28 August 1825. He knew he was different from other children from an early age – he often wore girls’ clothes in his youth and preferred being friends with girls.

Ulrichs went on to study at Göttingen University and Berlin University before he embarked on a career in the Hanoverian civil service – but his time as a public servant was cut short when rumours of his same-sex affairs started to swirl. He ultimately resigned before he could be sacked and he went on to work as a journalist for German newspaper Allgemeine Zeitung.

In 1862, Ulrichs took the significant step of telling his family and friends that he was sexually attracted to other men. At that time, the word “homosexual” hadn’t even been invented – and it was many years before the word “gay” was used to describe same-sex attraction. It was for this reason that Ulrichs started penning his own essays that allowed him to explore and innovate.

By the time he came out to his family, Ulrichs had come up with the word “Urning” to describe men who were sexually attracted to other men. This word featured prominently in his first five essays, Forschungen über das Rätsel der mannmännlichen Liebe (Studies on the Riddle of Male-Male Love).

In those essays, Ulrichs coined the word “Dioning” to describe lesbians, and he also came up with terms to refer to bisexual and intersex people. His terminology was based on passages from Plato’s Symposium.

It was in those essays that Ulrichs posited the idea that same-sex love was both biological and natural – that it was an innate, something people were born with and which they could not change. That idea was revolutionary in an era when homosexuality was rarely discussed in anything but negative terms.

Naturally, Ulrichs was nervous about putting his writings out into the world – which is at least part of the reason he initially published under the pseudonym Numa Numantius. However, he later acknowledged that the writings were his own and his final volume was published under his own name.

In his groundbreaking essays, Ulrichs campaigned for the legal rights of gay people. He initially believed that homosexuality in men was caused by having a female soul or “psyche” trapped inside the male body – however, he later argued that same-sex desire was entirely natural.

Using that logic, Ulrichs argued that same-sex relationships should be legally permitted – and he even suggested that gay people should have the right to marry.

As Hubert Kennedy in his article “Karl Heinrich Ulrichs: First Theorist of Homosexuality”, writes: “This was a major departure from previous and subsequent theories that saw the practice of homosexuality/’sodomy’ as an acquired vice.”

In one essay, Ulrichs wrote: “The Urning [gay man], too, is a person. He, too, therefore, has inalienable rights. His sexual orientation is a right established by nature.

“Legislators have no right to veto nature; no right to persecute nature in the course of its work; no right to torture living creatures who are subject to those drives nature gave them.

“The Urning is also a citizen. He, too, has civil rights; and according to these rights, the state has certain duties to fulfill as well.

“The state does not have the right to act on whimsy or for the sheer love of persecution. The state is not authorized, as in the past, to treat Urnings as outside the pale of the law.”

Ulrichs defended those whose sexual nature was ‘opposite of the which is usual’

That brings us to August 1867, when Ulrichs stood up in the Congress of German Jurists and issued a passionate call for gay people to afforded equality under the law.

Speaking in Munich in front of 500 lawyers, state officials and academics, Ulrichs argued that discriminatory anti-sodomy laws should be overturned.

“Gentlemen, my proposal is directed toward a revision of the current penal law,” he said, according to Robert Beachy’s 2014 book Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, as reported by The New York Times.

In his rousing speech, Ulrichs referred to gay people as a “class of persons” who were facing state persecution simply because “nature has planted in them a sexual nature that is opposite of that which is usual”.

That moment is generally accepted as the first public “coming out” in history – standing before his peers and advocating for the rights of homosexuals left no doubt in people’s minds about his own sexual orientation.

Historian Robert Beachy once said: “I think it is reasonable to describe him as the first gay person to publicly out himself. There is nothing comparable in the historical record. There is just nothing else like this out there.”

Needless to say, Ulrichs’ speech was not well received. The men gathered in the Congress of German Jurists shouted him down and loudly objected to what he was saying. He was ultimately forced off the stage, proving that society was not yet ready for the empowering message he wanted to bring to the masses.

That wasn’t the only opposition Ulrichs faced – his essays were banned and confiscated by police during his lifetime, and he was routinely ridiculed by a hostile media. Despite his best efforts, anti-gay laws continued to thrive and criminalise queer existence for many years to come.

Ulrichs eventually left Germany and relocated to Italy in 1880. He spent the final 15 years of his life there, where he earned a living by tutoring foreign languages. He also continued to write extensively – he published a journal in his later life which argued that Latin should be revived as an international language.

Ulrichs travelled around Italy for a few years before settling in L’Aquila. In 1895, shortly before his death, the University of Naples gave him an honorary diploma for his work. He died aged 69 in L’Aquila on 14 July 1895.

Today, there are streets named after Ulrichs in Berlin, Munich, Hanover, and Bremen. In Munich, his birthday is celebrated each year with poetry and a street party in the city’s Karl-Heinrich-Ulrichs-Platz, and L’Aquila, where he is buried, holds an annual pilgrimage to his grave.

While Ulrichs didn’t succeed in his battle to have anti-gay laws overturned, his pioneering writings and speeches are remembered today for their revolutionary qualities. Ulrichs wasn’t interested in bowing down to the status quo – he worked hard to shatter social norms around sexuality.

For that, LGBT+ people today owe Ulrichs a great debt.