Meet the activists who founded an anti-nuclear lesbian utopia in the throes of the Cold War

50,000 women converge on Greenham Common Peace Camp in 1983 to link hands and encircle the airbase in protest against the decision to site American cruise missiles there.(Reading Post/ Mirrorpix/ Getty)

Greenham Common Peace Camp was established in the 1980s to protest the government’s decision to allow the US to store nuclear missiles in the UK. It was also a lesbian utopia.

In 1975, the Soviet Union deployed the SS-20 Saber nuclear warhead and NATO began to fear that a nuclear strike on Western Europe was imminent.

The alliance agreed to deploy hundreds of missiles from the US to Western Europe from 1983, 160 of which were allocated to the UK. Almost 100 were based at Greenham Common base.

In 1981, a Welsh group named “Women for Life on Earth” set off to Greenham to march in protest against the nuclear missiles being stored on British soil, but soon realised that a march was not enough.

The women decided to stay and set up camp, and as word spread, women from across the UK and soon the world, came to join them. The settlement became known as Greenham Common Peace Camp.

Thousands of women used various protest strategies, from posters and songs, to breaking into the base, cutting holes in the fence and making a human chain of 50,000 women surrounding the compound.

Sue Say, now 57, arrived at Greenham when she was 19 years old, shortly before the “Embrace the Base” event.

Sue grew up in an unusual family – her mother was a Navy wren, and her father was conscientious objector and member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

“I was kind of between the middle of my mum and my dad,” she told PinkNews.

“But more more with my mum, because there were so many atrocities that were happening in the world, I thought that you needed to have an armed force of some kind, to protect innocent civilians if nothing else, so I accepted that the need for the military.

“The way the military was used was inappropriate, and I recognised that at a very early age… My ‘anti’ was always anti-government, not anti-military.”

Sue wanted to join the Navy like her mother, but her father wouldn’t allow it. “To spite him, I did business studies, because I knew he’d hate that, he was socialist to the core,” she said.

But Sue ended up working for a company which was called into help businesses, “looking at why they weren’t working properly, and then telling them how to fix it”. She “hated it with a passion”.

On one occasion, she was hired to help a company that sold car and bike parts, which had had the “revolutionary” idea of having women on the sales counters.

But the feedback from customers “came back as, ‘I don’t want to be told what to do by a woman, she doesn’t know what she’s doing, she should be in the kitchen or she should be on a back in the bedroom, but she certainly shouldn’t be giving advice about cars.’”

Sue had to tell the company to take all the women off the counters.

“That was the catalyst that made me think I can’t do this,” she said. “I cannot do this, this is a job I can’t do. That is wrong. These women were trained, they knew what they were doing.”

Sue Say went to Greenham Common Peace Camp for a weekend, and stayed for two years

Sue decided to take some time out, and having heard about the “Embrace the Base” protest, she said she decided to head to Greenham and check out the camp, intending to stay for a weekend.

But the time the weekend was up, she was a permanent Greenham woman.

Her first impression of the camp, which was a maze of incredible structures, tents and camper vans, and even tents around camper vans, was that it was “a ramshackle mess of women’s individuality”.

Women prepare for Christmas at Greenham Common Peace Camp, 1985. (Reading Post/ Mirrorpix/ Getty)

“Every woman spoke in a different accent,” she said. “It was bizarre. It was strange. It was odd because I’ve come from a little village where I was the only person who was odd and strange and a bit different.

“One, I wasn’t white. And two, I wasn’t straight. So I stood out quite a lot in my village.”

Sue had always known she was a lesbian, which she said means she doesn’t “have a coming out story to tell”.

“I haven’t got one of those because I was always who I was, and my parents just accepted who I was, and everybody around me just accepted that I was a little bit odd… The thing is, when you say you’re the only one in the village, you know damn well you’re not.

“Only, not everybody wants to be as open, so I discovered that you weren’t supposed to be open by the person that I first approached… I have to covertly meet her, because she wasn’t out.

“I never knew that I was supposed to, you know, feel badly about it.”

But the Greenham women were very open.

Sue explained: “Where there are women there will be lesbians… They will come because it’s safe.”

“I’ll be honest, I was 19 and it was a picnic,” she continued.

“Look at it! Instead of it being in a club scene where everybody’s got all these different things they’re bringing to it, we were all already actioning something together.

“So you’ve already got a lot in common with these women. And yeah, we were all horribly promiscuous. Yes, we were, we had a great time.”

As well as being a place for experimentation, Greenham Common Peace Camp was also a place for discussion, where queer women could safely speak about all aspects of their identities without fear of persecution.

“The 80s was definitely a time when women were exploring non-monogamy, they were exploring what lesbian relationships truly meant, there were lots of women that were together who didn’t have sex, or who didn’t believe that penetration was good, or didn’t believe this or that.

“This was a place where women could explore and discuss to death, any of those issues. And it was wonderful, because where could you have discussed, you know, your clitoris? Where could you have done that?

“You could never have done that, I could never have been free to join in a discussion around how we feel about things, exploring jealousy, exploring this idea and this idea, and we’re all working together, and nobody’s got a better role or a bigger role, we’ve all got our role.”

Police frequently targeted the peace camp, but not all Greenham women suffered in the same way

Greenham Common Peace Camp was hit with massive local and national opposition, including from police, the Ministry of Defence, supporters of the nuclear deterrent and locals who would even refuse to serve the women in shops and pubs.

To understand the horror and disgust directed towards the camp, “you’ve got to see the context”, Sue said.

“Back then, women were still going to church and getting married and giving a vow to obey.

“Back then, when I went to camp, if a man raped his wife, there was no crime. No crime.

“Women didn’t have the power to go anywhere or do anything. They knew what would happen to them in certain situations, and that nothing would happen regarding the law. It was allowed, it was permitted, it was acceptable, because you married him.”

She continued: “For those women from that era, to abandon their husbands, taking their children with them, and living at camp, was a big statement. It was: ‘I’m not leaving my children with you. I’m taking them with me, and I’m gonna save the planet, and bugger you.’

“That never happened, you don’t say bugger you to your husband, he can do what he likes to you because you’re married.

“Women suddenly realised there was something much bigger in the world than this little tight circle of nuclear family that they weren’t happy with. Women who were lesbian back then got pushed into marriages, pushed into all sorts of situations, because you couldn’t be, society didn’t accept it.”

She added: “Unless they understand what it was like to be a woman back then, people wouldn’t understand just how revolutionary it really was, and just how much it made men angry.”

The camp was constantly targeted by police, who would arrest women in the middle of the night, whether they had committed a crime or not.

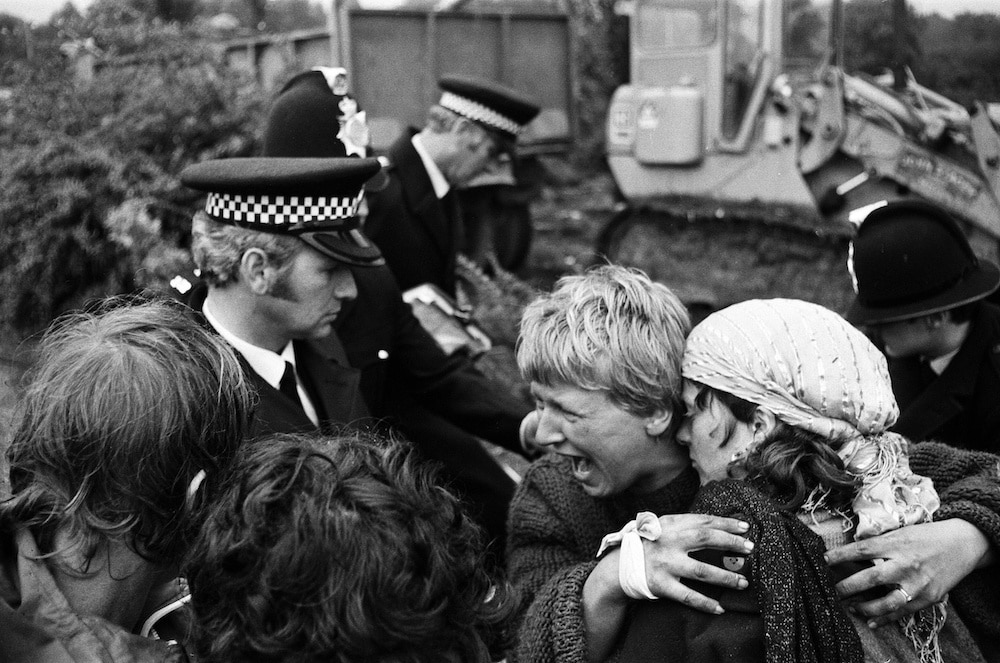

Greenham Common Peace Camp, 1982. (Reed White/ Daily Mirror/ Mirrorpix/ Getty)

The first time Sue went to jail, it was for something she didn’t do. At the time, she said she believed two things that might seem “comical” now.

Firstly, “that the police told the truth… All of them, they wouldn’t dream of not doing that”.

Secondly, that “prison was there to hold the dangerous members of our society away from us, because they’re violent and aggressive, and they’ll hurt people”.

“I knew women were oppressed, but I thought they were just equally squashed by men,” she said.

“I didn’t realise there were other elements, and so my education began… I had to reassess everything, all these previous assumptions that society was actually sane.”

“I’m a Black lesbian,” she continued. “And when I went into court with my white working class mate for the same offences, with the same amount of pre-offences, she got 14 days and I got 28.

“ I got strip-searched, and so did she, but our middle class white friend who was up for the same charge, didn’t.

“I was strip-searched, virtually every time I was charged. I got strip-searched in the base, and then at the police station, virtually every time.

“That did not happen to the white middle class women… It was used as a tactic to demoralise the working classes [and the queer women], and they got away with it, because it’s only a lesbian, she can’t complain.”

Greenham Common Peace Camp demonstration at RAF Greenham Common, 1982. (Reed White/ Daily Mirror/ Mirrorpix/ Getty)

Sue Say lived at Greenham Common Peace Camp for two years, although this time was peppered with jail stays and court dates.

During that time, she was part of a team of women that took the government to court over illegal strip-searching and won, resulting in a change in law.

Her time at Greenham has had a profound impact on the rest of her life: “What I learned was that once your eyes are open, you can’t shut them. And once you’ve seen that there’s something else playing underneath, you don’t always take what you see on face value.”

Activism was in her blood, and in the years that followed her departure from Greenham, she joined anti-apartheid protesters at South Africa House, protested the closure of South London Women’s Hospital, and fought for the right of Sri Lankan national Viraj Mendis to stay in the UK.

“I sat at Greenham, and the world came to me,” she explained.

“It was like having the internet, but much more personal. Because you could ask the direct question and that person, you were looking them in the face and they’d tell you the answer.

“It was the value of having all those different peace women from different countries, and different cultures within our own society… it gave me an understanding that I wouldn’t have had sitting in my little village.

“That is what opened my eyes and widened my perspective and made me think, ‘Ah, things aren’t just what they presented us, and I need to look a little bit further into everything.”

The last missiles left the Greenham Common base in 1991, but the final protesters refused to leave until the last fence was taken down in 2000.

Last month, former residents Kate Kerrow and Rebecca Mordan published a book titled Out of the Darkness: Greenham Voices 1981-2000, to preserve the vibrant history of the Greenham Women.