The long, troubling history of pink toys for girls and blue for boys

Pink and blue baby shoes. (Envato/rawf8)

Pink and blue baby shoes. (Envato/rawf8)

A brief investigation into the history of gender and children’s toys.

The recent news that Lego is making its toys “gender neutral” begged the question: When – and why – did toys become gendered in the first place?

We all know that pink is for girls and blue is for boys. Two genders that have been neatly divided into blue and pink. That’s the story we’ve long been told – and it’s the way that many products, especially clothes and toys, are marketed to parents for their kids.

Often, this looks like a pink version of a product for girls and a blue version for boys. Sometimes, companies just make a pink version of an existing toy and market it to girls; occasionally, this will be more expensive than the original toy.

And this phenomenon isn’t limited to children, either – just look at pink razors, pens, hammers and even ice picks especially for women.

Stock photo showing a “pink lady shaver”. (Envato/jirkaejc)

A history of pink and blue

Despite what marketing campaigns today would have us think, pink didn’t become established as the “girl” colour until after the First World War; before then, boys wore it, too.

Gender-specific clothes and colours were first properly established in the US in the 1940s. It’s true, then, that while we now see pink as a “girls” colour and blue as “for boys”, this has not always been the case.

In fact, one hundred years ago, the opposite was actually true: blue, because of its associations with the Virgin Mary, was well-established as the correct colour for girls to wear; while pink, with its links to the strong, masculine colour of red, was the colour recommended for boys.

And this rule had been in place for more than a century, since the 1800s. Pink for boys, blue for girls. For hundreds of years, it was considered the norm for little boys to wear pink dresses until they were six or seven.

Barbie dolls on display, showing a “feminine” gender with skirts, heels, long hair and make-up. (Chesnot/Getty Images)

Before the 1800s, most young children wore white, because it was easier to bleach clean. Children of different genders wore clothes of the same colours, based on practicality, and not a need to be able to tell the sex of a child from their clothing.

But now, society not only requires that a child’s sex is indicated by their clothes, but pink and blue have swapped.

This is true not just of clothing, but also toys, books, magazines and just about anything else that can be marketed. So, how did pink and blue transition from one gender to another? And why did it become so important to split children into two genders?

Lego: A case study of gendered toys

This month, toy giant Lego announced it would be dropping the binary “girls” and “boys” labels from its toys, in an effort to combat harmful gender stereotypes.

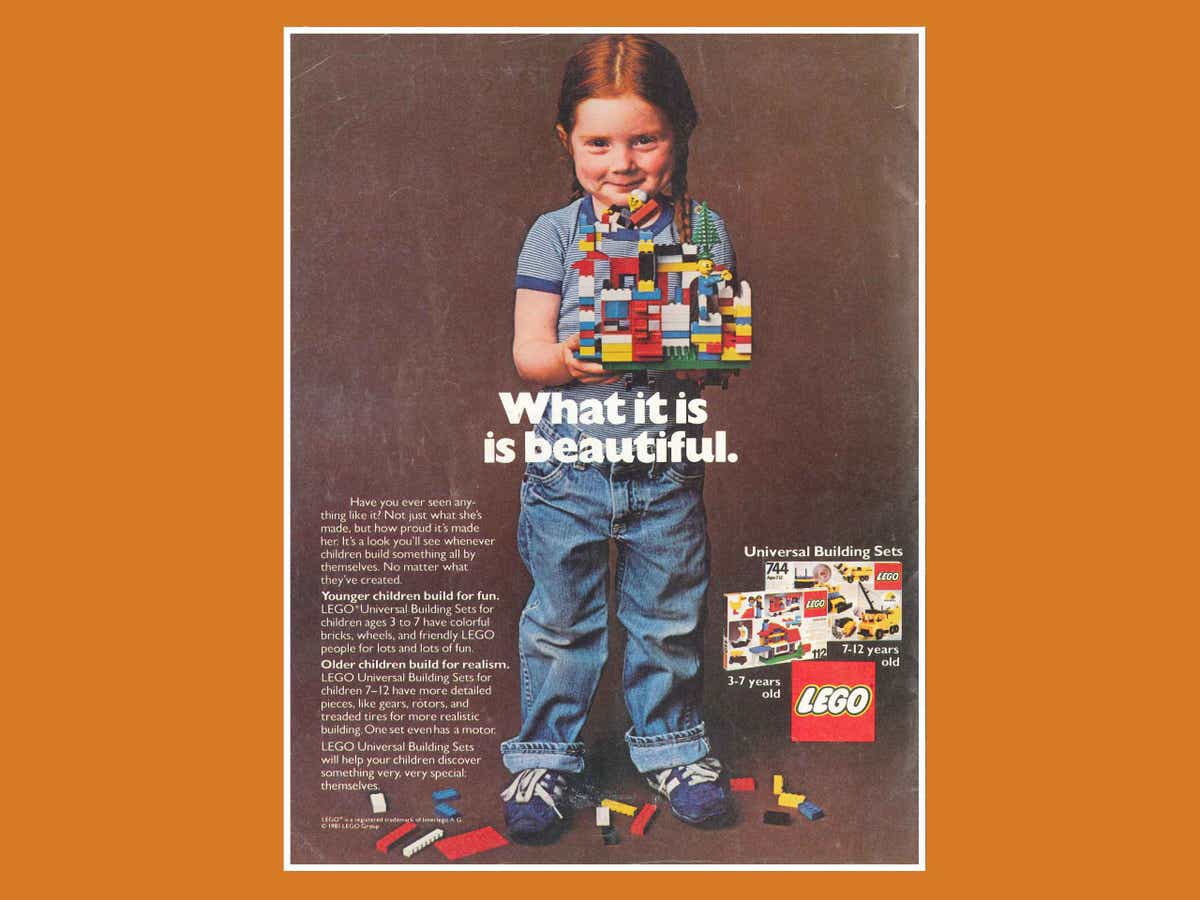

The move was widely welcomed. But what’s surprising is that, as recently as 1981, Lego wasn’t gendering its toys at all. In a now-infamous ad, a little girl holds a Lego set with the accompanying text that this toy is for “younger children” who “build for fun”.

Lego’s ‘What is Beautiful’ advert from 1981. (Lego)

Not a “made for girls” or special pink Lego brick in sight. But fast-forward to 2011, and Lego introduced a range, Lego Friends, that was “especially for girls”. It’s significantly pinker than the rest of Lego’s offering.

Lego is not alone – most toy manufacturers have worked to an increasingly rigid gender binary in the last 50 years, with markedly feminised, pink versions of products marketed exclusively to girls.

This has been accompanied by an increase in the division between the type of toys marketed to girls, and those for boys. More “masculine” toys – those linked to construction, racing, trains, science, fighting, action figures – are for boys, while girls are marketed princesses, kitchen play-sets, hairdressing, doll houses, mini cleaning sets and baby dolls.

A Lego advertisement at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport shows a male figure in blue. (Miguel Candela/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

The gender binary and late-stage capitalism

What do pink toys for girls have to do with late-stage capitalism?

Well, capitalism relies on a nuclear, traditional family in order to function. This means that women do unpaid labour rearing, clothing and feeding the current workforce, their husbands, and the future workforce of their children.

Spot the similarities here with toys marketed towards girls promoting cooking, cleaning and child-raising.

For capitalism to work, it’s very important that marriage remains heterosexual, that there are two different genders to take on these complementary roles, and that men are “masculine” and women “feminine”.

Take a 1950s middle-class housewife in the UK, who was expected to conform to an extremely traditional and heteronormative gender role. She stayed at home and did the cooking, cleaning and child raising, unpaid, while her husband worked in exchange for money outside the home.

Since that time, in general, there have been some improvements in gender equality between men and women. LGBT+ and feminist gains mean that more middle-class women now go to work, often paying working-class women (who were always expected to work) to cook, clean and take care of their children.

The growing acceptance and visibility of LGBT+ families, alongside increasing numbers of middle-class women in board rooms, has disrupted the nuclear family unit that capitalism relies on. Furthermore, in its late stages, capitalism is losing its grip. Socialist ideas – like the four-day working week and longer, more equal, paid parental leave – are becoming increasingly mainstream. More talk of a tax on the rich, as flouted by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on her Met Gala dress, is another way that we see an increasingly left-wing world view taking hold.

So, is it any surprise that huge, international companies – themselves a product of and agent for capitalism – are responding by doubling-down on enforcing a rigid gender binary? We don’t think so.