I was sexually abused as a nine-year-old boy. People said I ‘was asking for it’ because I’m gay

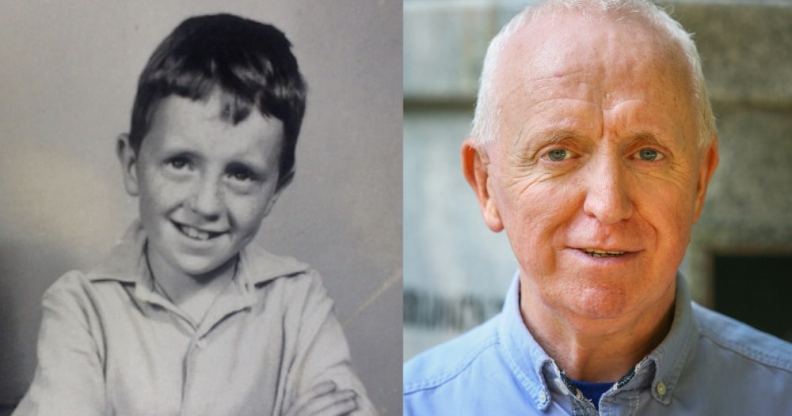

Patrick Sandford pictured at the age of 9 (L) when his primary school teacher first started sexually abusing him, and Patrick pictured on the right in the present day. (IICSA)

When Patrick Sandford was just nine years old, he was groomed and sexually abused by his primary school teacher. Warning – sexual abuse.

It would be more than 20 years before Patrick, now an acclaimed theatre director, would feel able to speak openly about the abuse he endured as a child. When he finally did, people made appalling, shocking remarks conflating the abuse with his sexual orientation.

“Quite often I would talk about my abuse and someone would come back: ‘Oh well of course if you’re gay, you were probably asking for it,’” Patrick tells PinkNews.

“I used to get: ‘If you were gay, that must have made the abuse easier or it must have made it more inevitable.’ Basically what they were saying was, if I was gay they didn’t have to worry about it as much because maybe I deserved it.

“This was not just the authorities, this was general conversations with people. There’s a sense that if gay men are promiscuous, that somehow makes the abuse alright. It’s a totally distorted view of human sexuality.”

Patrick Sandford aged nine, photographed around the time his teacher started abusing him. (Provided)

Patrick Sandford grew up under the shadow of child sexual abuse

Patrick’s experience is backed up by research. A report from the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), published 24 May, found that LGBTQ+ survivors and victims often have to contend with victim-blaming attitudes in addition to harmful, outdated ideas about sexuality.

Some who experienced child sexual abuse were told they had brought the sexual abuse on themselves because of their LGBTQ+ identity, while others were told they were gay, bi or trans as a direct result of the abuse.

For Patrick, the impact of those harmful attitudes was severe. He grew up feeling profound shame about his body, which was exacerbated by the fact that homosexuality was still illegal.

“I was queer-bashed several times, I was beaten up by the police. Even worse things were done to me – I was gang-raped. But of course I was gay so I put myself into that situation – that’s what I would have gotten at that time. I had so much internalised homophobia, so much internalised shame, that all the shame that was given to me by the abuse, I didn’t recognise it as that. I just blamed all my insecurity – all my body shame particularly – on the fact that I was gay.”

The abuse he suffered as a child coupled with the shame of growing up gay led Patrick to a dark place mentally – he became convinced that he was disgusting to other people and that he should hide himself away.

Now I can see that all that was because of the shame put into me by my primary school teacher.

“When I was at university I used to hide in my room and not go out till after dark because I didn’t want people to see me because I thought they could see that I was queer, that they would condemn me,” he says.

“In fact, now I can see that all that body shrinking and body shame was because of the shame put into me by my primary school teacher. That gave me a core identity that anything to do with my body was bad.

“I actually got to the point where when I was on the tube in London, when everybody got off the train at Oxford Circus, I used to think it was because they couldn’t stand to be in the carriage with me, that I was smelling or there was an aura around me. I think I was probably mentally ill, although I didn’t go to see any therapist at that stage. Being gay was such a shameful thing, but that just compounded the shame of the abuse.”

Patrick Sandford. (Provided)

Things finally started to look up for Patrick when he discovered the theatre. “It meant I could act and be somebody else. I could get a new identity, and as soon as I was in the theatre when I was 25, 26, I was among people where there was much more sexual liberation, where being gay was accepted.”

While Patrick found acceptance and love in the theatre, he still had to come to terms with the abuse he had suffered as a child. He wasn’t able to speak openly about his experience for around 25 years after the abuse occurred. At the age of 35, he started going to therapy – at that time, he still thought all of his problems were because of his sexuality.

“When I first went to therapy, my presenting symptom was: ‘Oh my God, I’m a shameful, guilty homosexual – can you help me?’ I can’t believe it, but that’s what I did. The therapist, to do him justice, said: ‘OK, so you’re gay, what’s the problem?’ I happened to hit on a good therapist and he was terribly reassuring, but then of course my problems didn’t stop because that’s when I realised they were much more about something else – they weren’t about being gay, they were about abuse.”

Patrick always knew that his teacher had done “bad things” to him, but before he went to therapy, he didn’t know just how destructive and harmful it was.

It’s taken me a long time to come to terms with the fact that sex is something good and healthy and thoroughly enjoyable.

“I knew it was horrible and I knew I hated it and I knew I could never tell anybody about it because it was so bad and so shameful,” Patrick says. “It was in my late 30s that I began to understand the abuse had had catastrophic effects on me in terms of forming relationships and trusting people. Looking back at my first gay relationships, I feel sorry for the men now because I think I must have been rather difficult to be with because I was so shame-bound around anything to do with sex.

“It’s taken me a long time to come to terms with the fact that sex is something good and healthy and thoroughly enjoyable. It’s taken me a long time to reach that – now, younger gay men, they feel surprised by that, but I’m not ashamed to admit it, because I don’t blame myself for that. I blame what happened to me.”

Patrick shared his story on stage and screen

Ultimately, Patrick was able to find himself in the theatre – and therapy helped him to confront his past head on. In 2016, he tackled his abuse in the autobiographical play Groomed, which won critical acclaim for its unwavering exploration of trauma. Three years later, he reimagined that play as a film.

Patrick Sandford the Groomed film.

Tragically, the man who abused him never faced any repercussions. Patrick believes he died shortly after the abuse ended from cancer.

“That is what my mother told me, unless of course he had lied and disappeared into the ether, but as far as I know he never faced anything,” Patrick says.

Now that the IICSA report is published, Patrick is hopeful wider society can start having a more grown-up, honest conversation about what a perpetrator of child sexual abuse looks like – and what we can do to prevent the abuse of children.

“We think that perpetrators are evil men in white coats – perpetrators are everybody. It’s massive, the scale of it. It’s every bit as big as AIDS or COVID, it’s a health pandemic, and we should do something about it.”

Patrick Sandford’s film Groomed will be screened at the Garden Cinema on 15 June.

If you’ve been affected by the issues raised in this story, you can access support for LGBTQ+ people via Galop and support aimed at men, including queer men, at 1 in 6.

Rape Crisis England and Wales works towards the elimination of sexual violence. If you’ve been affected by the issues raised in this story, you can access more information on their website or by calling the National Rape Crisis Helpline on 0808 802 9999. Rape Crisis Scotland’s helpline number is 08088 01 03 02.

Readers in the US are encouraged to contact RAINN, or the National Sexual Assault Hotline on 800-656-4673.