UK’s ‘first monkeypox patient to go public’ warns homophobia is already setting in

James McFadzean has been described in the press as Britain’s first public case of monkeypox. (James McFadzean)

Monkeypox is already being treated as a “gay disease” in the same way HIV was, Britain’s “first monkeypox patient to go public” has warned.

Since 13 May, when the first case in the monkeypox outbreak was reported, health authorities have recorded more than a thousand cases across 32 countries, including 366 in the UK (as of 9 June).

Among them is James McFadzean, a gay London-based PR manager.

After a HIV diagnosis that saw his life in the United Arab Emirates fall apart, McFadzean came back to Britain only to test positive for monkeypox.

McFadzean didn’t leave the house for weeks even as he received muddled advice – or none at all – from medical professionals about the rare virus.

Now recovered, McFadzean tells PinkNews his experience with the virus, while rough, was bearable – the homophobia he’s seen, however, not so much.

Much of the news coverage he’s seen, he says, has echoes of that of the AIDS epidemic – full of stigmatising language that seemingly blames queer men for having sex.

The 35-year-old’s family, especially his mother, were immediately wary of monkeypox being made out to be a “gay disease” when he first told them he had acquired it, he says.

And he’s certainly not alone, with the World Health Organization condemning the “racist and homophobic” media coverage.

Once he went public with his story to the MailOnline, McFadzean says he was too scared to read the MailOnline comment section, mindful of how his sexuality would be used to blame him.

“It was stressful and lonely,” he said of the weeks he spent in isolation at his home in London.

“There were definitely reactions from people that made it out [to be a ‘gay disease’]. That is the narrative that’s been given.”

Monkeypox lesions. (UKHSA)

It’s a delicate balancing act: alerting the public about who has been infected with monkeypox while also avoiding the suggestion the virus is confined to that demographic, McFadzean says.

The UKHSA says close contact – including “sexual contact” – with infected skin is one of the main ways monkeypox is being spread. This can include skin-to-skin contact, kissing and respiratory droplets at a very close range.

The UKHSA adds that “most” of the 366 confirmed cases in Britain “have been in men who are gay, bisexual or have sex with men”. Some international cases have seen a similar trend, with a few patients linked to a Pride event in the Canary Island and a kink festival event in Belgium.

But because of this, McFadzean feels the mainstream media has suggested queer people – himself included – only contract the virus because they’re “having sex with loads of people”.

“That is adding to the stigma. Even if you’re not openly saying ‘it’s a gay thing’ the inference is there. ‘Gay people love sex, they have massive orgies every weekend’. They’re playing off that stereotype – it’s not helping people,” he says.

“The pop-ups from Grindr and the gay press have been great,” he adds, “but the mainstream press needs to take more responsibility.”

Health officials have been at pains to stress that monkeypox can infect and be spread by anyone – not just queer men. Yet the sustained focus on gay and bisexual men may carry its own risks, such as discouraging some men to test for monkeypox, McFadzean warns.

“If there are men who have sex with men who aren’t gay or aren’t out who feel unwell or have a rash, they may not report it because they feel this is going to blow their secret,” he says. “So are we alienating people from actually seeking advice where they need it?”

Monkeypox ‘brought back memories’ of the AIDS crisis for queer men, says HIV expert

Health experts have long said that stigmatising the LGBTQ+ community at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s greatly slowed down efforts to control it.

McFadzean is no stranger to such hostility. He lived in Dubai for four years before testing positive for HIV in February. “When I was diagnosed with HIV, I lost my job, I got taken to a government facility, I got deported, lost my house, everything,” he says.

Coming back to Britain, he braced himself for the same level of bigotry. Thankfully, from friends to other queer men, everyone has been positive. “I felt a sense of pride,” he adds.

But while public attitudes toward HIV have moved on, other forms of anti-gay stigma still linger.

Matthew Hodson is among many health experts fearing that monkeypox could – and even has already – received the same treatment HIV did. Health agencies, governments and people must learn from the mistakes made, he says.

“I’ve seen a lot of gay men compare [monkeypox] to HIV. It’s almost like a post-traumatic stress kind of response,” Hodson, executive director of aidsmap, tells PinkNews. “When you see those reports about a virus which seems to be affecting gay and bisexual men, it brings back a lot of memories and it can be quite triggering.”

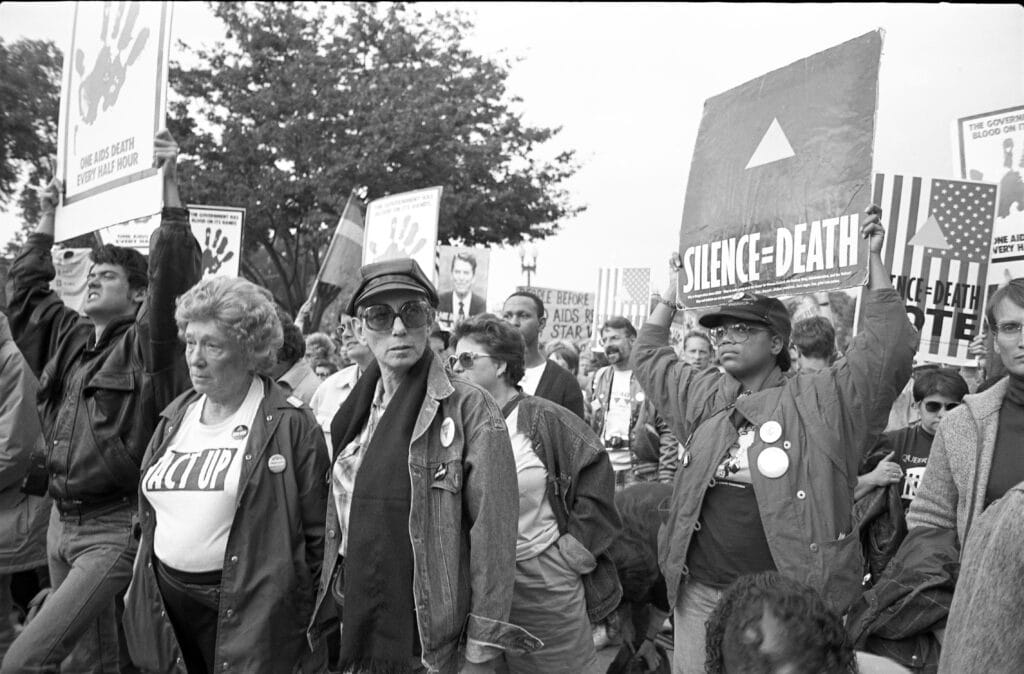

ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) protest at the headquarters of the Food and Drug Administration in 1988. (Catherine McGann/Getty Images)

Hodson says he’s not surprised the virus has put the LGBTQ+ community on edge.

“Homophobes are, of course, going to seize upon that and use it as another rod to beat us with,” he says.

Data so far suggests that people living with HIV who develop monkeypox do not appear to have any worse outcomes than those who don’t. Those living with HIV are so far not recommended to take any additional precautions other than those already recommended to the wider population.

Hodson stresses that monkeypox isn’t something people living with HIV need to panic or be alarmed about. But he acknowledged that, like McFadzean says, handling an outbreak that has disproportionately impacted queer men is a balancing act.

“Although it’s really important that we stress that this isn’t, by any means, a gay disease, it is also important to note that it has been gay and bisexual men who have been the vast majority of cases so far,” he says.

“It’s really important that gay bisexual men are informed about it so that they can take the precautions that feel right for them.”

McFadzean says he felt a separate sense of déjà-vu regarding monkeypox, taking him back to the conspiracy theories that were rife during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. It didn’t take long for social media sceptics to accuse him of being a “government plant”.

“They’re saying I’ve been paid by the government to scare people into believing monkeypox exists, that it’s something in the COVID vaccines,” he says.

“Obviously I look at that and I laugh,” McFadzean says, adding: “I’m no conspiracy theorist – and I’m certainly not a government plant.”