Monkeypox vaccine: Who is eligible, how it’s being distributed and other vital facts

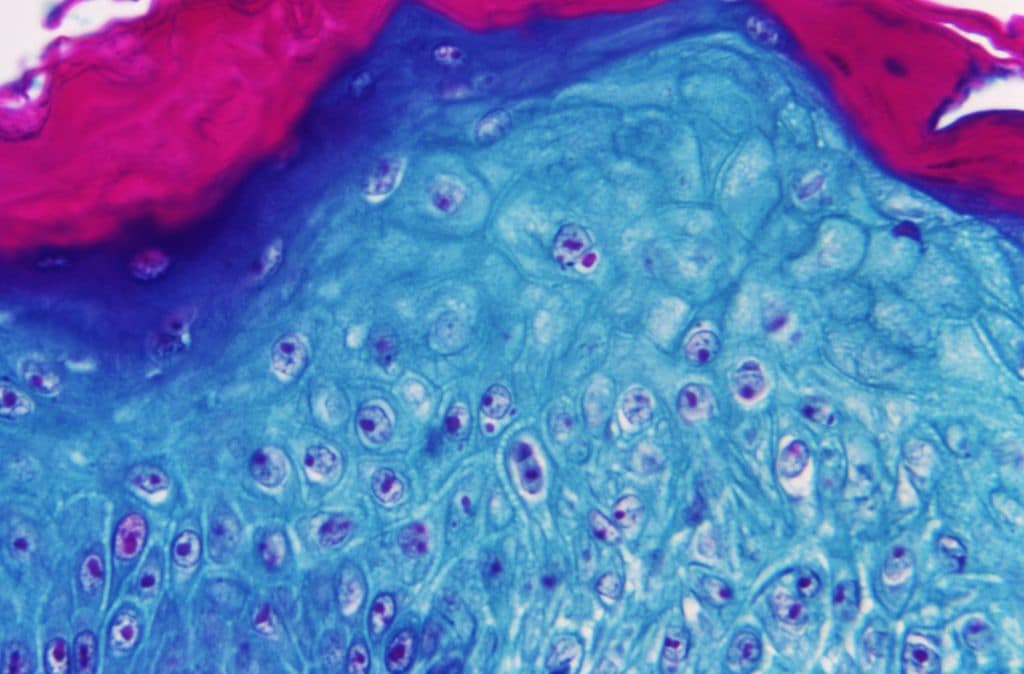

Monkeypox lesions. (MarioGuti/Getty Images)

In May, the UK began stockpiling smallpox vaccines to be used as vaccines against monkeypox, a very similar virus, as cases moved into triple figures.

But two months later, with UK cases soaring, access to vaccination is sparse and widespread confusion remains about how to get a jab.

Here is everything we know about the monkeypox vaccine.

How does the monkeypox vaccine work?

The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) told PinkNews that to date, the country has purchased “nearly 30,000 doses” of a smallpox vaccine called Imvanex.

Imvanex, supplied by Bavarian Nordic, is typically used to prevent smallpox is adults, but is now being used to prevent monkeypox as the viruses are so similar.

According to the European Medicines Agency, Imvanex contains a modified form of the vaccinia virus called vaccinia Ankara, which cannot produce disease in humans, but helps produce antibodies that are effective against smallpox and monkeypox.

Monkeypox scabs. ( CDC/Getty Images)

The smallpox vaccine has proved to be about 85 per cent effective in preventing monkeypox, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The vaccine is very safe, but possible side effects do include flu-like symptoms and soreness or skin reactions at the injection site.

“We are closely monitoring demand and remain in discussions with the manufacturer so we can quickly procure further doses as required,” a UKHSA spokesperson said.

Who is eligible to get the Imvanex smallpox/monkeypox vaccine?

There are currently three groups of people eligible for vaccination against monkeypox.

The first group is gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men, who are at the highest risk of coming into contact with monkeypox.

Although anybody can catch monkeypox, the vast majority of cases have been among young, queer men in big cities, especially London.

Queer men are thought to be at the highest risk of contracting monkeypox if they have “a recent history of multiple partners, participating in group sex, attending sex on premises venues or a proxy marker such as recent bacterial STI (in the past year)”, according to the UKHSA.

The second group includes those who are likely to be exposed to monkeypox because of their work, for example those who work at sexual health clinics, in the sex industry or in saunas.

The third is those requiring post-exposure vaccination, either because they were exposed to the virus by a close contact, or exposed to it at work.

Although there is little evidence on the effectiveness of the smallpox vaccine in protecting people after they have been exposed to monkeypox, the UKHSA recommends that a post-exposure jab should be “offered ideally within four days of exposure, although may be offered up to 14 days in those at ongoing risk, or those who are at higher risk of the complications of monkeypox”.

There are several ways to access a monkeypox vaccine if you’re eligible

Different services and sexual health clinics are taking varying approaches to rolling out the monkeypox vaccine, Dr Claire Dewsnap, physician and president of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH), told PinkNews.

Because vaccine supply is limited, the government is providing doses to clinics that see higher numbers of high-risk people, for example sexual health clinics in London.

Of the clinics that do have vaccines to offer, two approaches are being taken.

“We’ve been given approval to either do opportunistic vaccination, or targeted vaccination,” said Dewsnap.

“Opportunistic might be, for example, everyone that comes into a PrEP clinic gets offered a vaccine. In Sheffield, where I work, that’s what we’re doing to start with, all the PrEP clinics will have additional time put on the end of their appointment to offer the vaccine, and you can have it if you want it.

“In other clinics they’re only doing targeted vaccination, because they feel that there’s a lot of pressure on the vaccine, so they have to go for the highest-risk people. In those cases, people are being offered appointments, they’re being contacted directly. In some clinics, they’re doing a bit of both.”

A healthcare worker prepares to administer a monkeypox vaccine in Florida. (Getty/ Joe Raedle)

Even clinics that do have vaccines are struggling to give service users consistent access, as they can only restock on doses once they have completely run out.

While the government is trying to procure more vaccines, the doses currently being offered are “slightly older”, Dewsnap said, meaning that their expiry dates are sooner.

“They’re trying to limit how many clinics get vaccines so that the vaccine that we have doesn’t go out of date,” she explained. “When they run out of vaccine, they can immediately order more.”

In a message to those who are eligible for vaccination, Dewsnap said: “Find out what your local clinical doing, it should be on their website or they should be tweeting about it, [but] obviously contact them if it’s unclear.”

Monkeypox and the vaccination roll-out is putting huge pressure on sexual health services

The monkeypox outbreak has stretched sexual health services beyond their limits, and not just when it comes to vaccine roll-out.

Dr Claire Dewsnap explained: “In addition to that some of the obstacles to getting vaccinated, over the last 10 years clinics have had a massive amount of money taken out of their budgets… That reduction in budget has impacted on the amount of staff available.

“So if you then add into that a brand new demand, there are going to sometimes be obstacles at certain clinics.”

She continued: “What really worries physicians like me is that we know for a fact that 20 per cent of other services – general screening for STIs, the general management of infections, access to PrEP, access to contraception – are already being pushed out by the demands being placed on services by monkeypox.

“So it’s not just a worry about not getting the vaccine out quick enough, we’re also worried about other things like patients not being able to get into the clinic, and not being able to access clinics in the way they would normally be able to expect.”

A section of skin tissue, harvested from a lesion on the skin of a monkeypox patient, under a microscope. (Smith Collection/ Gado/ Getty)

Earlier this week, leading sexual health groups sent a joint letter to health secretary Steve Barclay, as well as to NHS and UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) bosses, urging the Department of Health and Social Care to inject extra funding to stem the monkeypox outbreak.

“Urgent action is needed to prevent monkeypox from becoming endemic in the UK and super charge the targeted vaccine programme for gay and bisexual men,” the groups said, calling for £51 million in funding to keep on top of climbing monkeypox cases.

Richard Angell, campaigns director at Terrence Higgins Trust, one of the groups that signed the letter, told PinkNews: “There are significant issues when it comes to the targeted vaccine programme. We are concerned about the procurement of the vaccine and having enough doses quickly enough to protect those most at risk. We need at least another 120,000.

“Then there’s a lack of coherent approach – and urgency – for getting it into the arms of those who need it.

“Lastly, sexual health services were already on their knees prior to the monkeypox outbreak and are now being expected to lead the country’s response without additional resource or staffing.”

Patients whose access to sexual health services is suffering must make some noise, experts say

Dr Claire Dewsnap said that, unfortunately, the best way to ensure that sexual health services are reaching those who need them is for service users to make a lot of noise and force the government’s hand.

She said: “The way that you could do that confidentially is you could you could complain to your local clinic about your lack of access, formally… They do listen to patients. If you can’t get into your clinic, complain that you can’t get in.”

The wider community can also help, Dewsnap said, even if they aren’t directly affected by monkeypox’s impact on sexual health services.

“Anybody that’s willing to write a generic letter to their MP about the impact of monkeypox on sexual health services would be very much encouraged,” she said.

“A letter saying, ‘I know my sexual health service is struggling. What are you going to do about it?'”