Monkeypox expert answers most common questions, from sex and symptoms to vaccines and transmission

Protesters at the San Francisco Federal Building demand that the federal government respond quickly to the recent San Francisco monkeypox outbreak. (The Washington Post via Getty/ Marlena Sloss)

There’s a great deal of worry among LGBTQ+ people about monkeypox right now.

The virus, once found predominantly in parts of central and west Africa, has been spreading rapidly among gay and bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men, across the world in recent months.

There’s a lot of confusion out there about monkeypox, who should be getting vaccinated, and how the virus is transmitted – which is why PinkNews asked our readers to submit questions.

We put those questions to Mateo Prochazka, an infectious disease epidemiologist with the UK Health Security Agency.

How easy is it for monkeypox to be transmitted outside of sex? Can it be passed on through fabrics or toilet seats, for example?

Mateo: The main route of transmission for monkeypox continues to be through sexual contact, but it is important to note that this is not just sex in the stricter sense – it can also include things like cuddling, being very close to one another with our clothes on, deep kissing, or sometimes sharing towels or linens or personal objects where the virus may be present. Because this is not an STI, but is an infection that is being transmitted during sex, we need to have other considerations including those related to our personal objects or the close direct interaction that can sometimes not be of a sexual nature itself but can expose us to the virus.

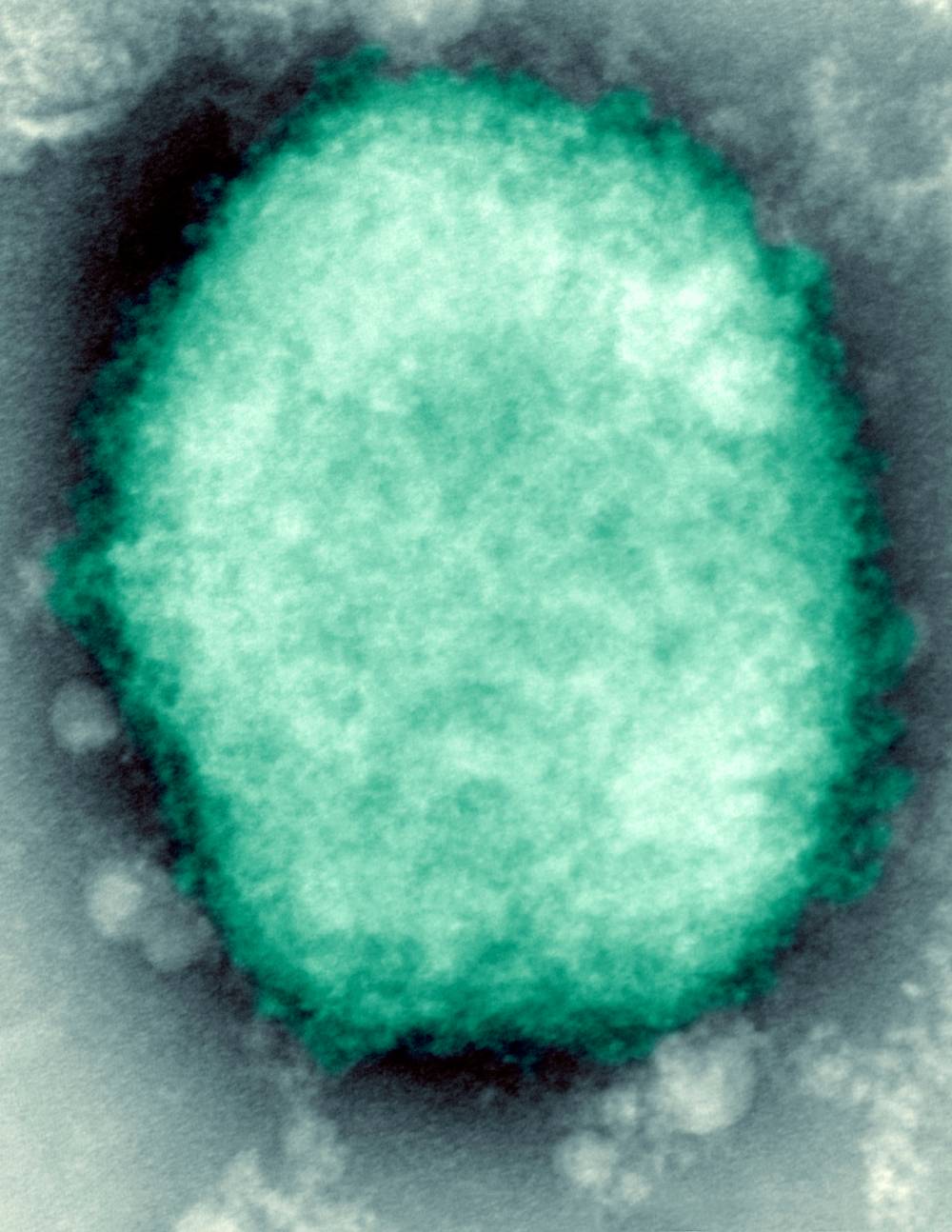

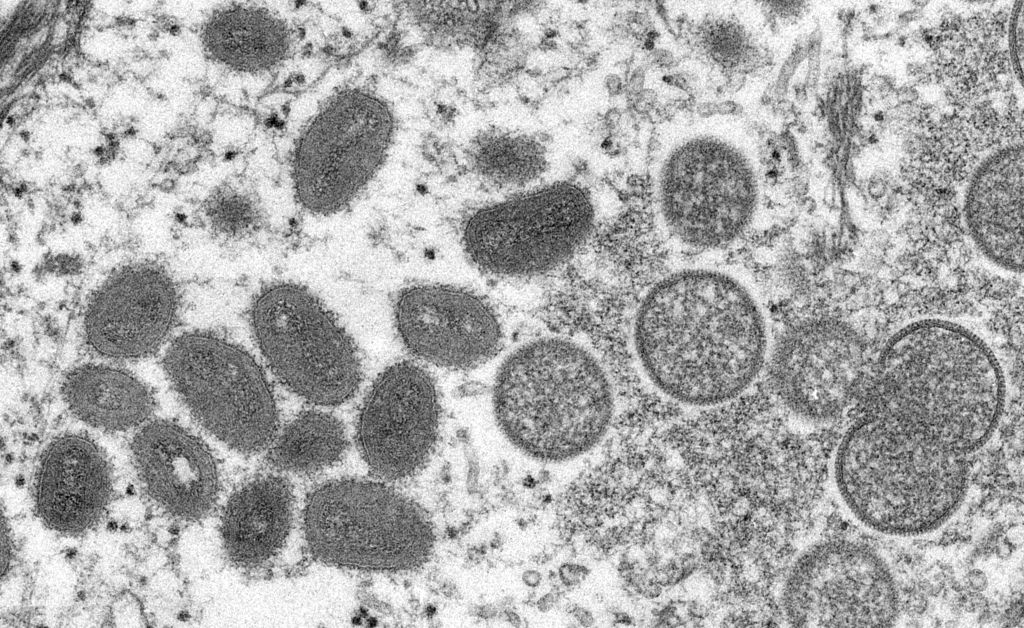

Monkeypox is a viral zoonosis (a virus transmitted to humans from animals) with symptoms very similar to those seen in the past in smallpox patients. (Getty)

That’s not to say there’s not other routes of transmission that can facilitate the spread of monkeypox, for example, respiratory droplets. Usually the kind of respiratory droplets that are associated with monkeypox transmission are larger droplets, the kind of short distance ones that will require prolonged and close contact to have transmission happen. These droplets usually fall to the ground because of their weight so they are not suspended in the air in the environment in the same way that, for example, COVID transmission may happen.

However these drops can fall onto surfaces including linens or towels so when you share bedding or you share clothes with people who may have monkeypox you can be exposed to the virus in those surfaces and the virus could enter your body and you could establish an infection. But that’s not to say that’s the most common way of getting the infection. The most common way of getting the infection continues to be through sexual contact.

Can somebody who’s at an early stage of monkeypox, or someone who hasn’t started showing symptoms yet, pass it on?

There are some cases in which the virus has been isolated from people who have no symptoms, but to this date there is no demonstrated case of transmission from someone who was completely asymptomatic passing the infection on to another person. That’s not to say that that cannot happen. Asymptomatic transmission is a possibility, but we know that the highest infectiousness – the highest likelihood of transmission – happens when someone with the infection has lesions on their skin or has symptoms.

Do I need to consider getting a monkeypox vaccine if I received a smallpox vaccine as a child?

The virus that causes smallpox and the virus that causes monkeypox are part of the same family, which is called orthopoxviruses, and we know that there is cross protection between both, meaning that the same vaccine can work for both infections.

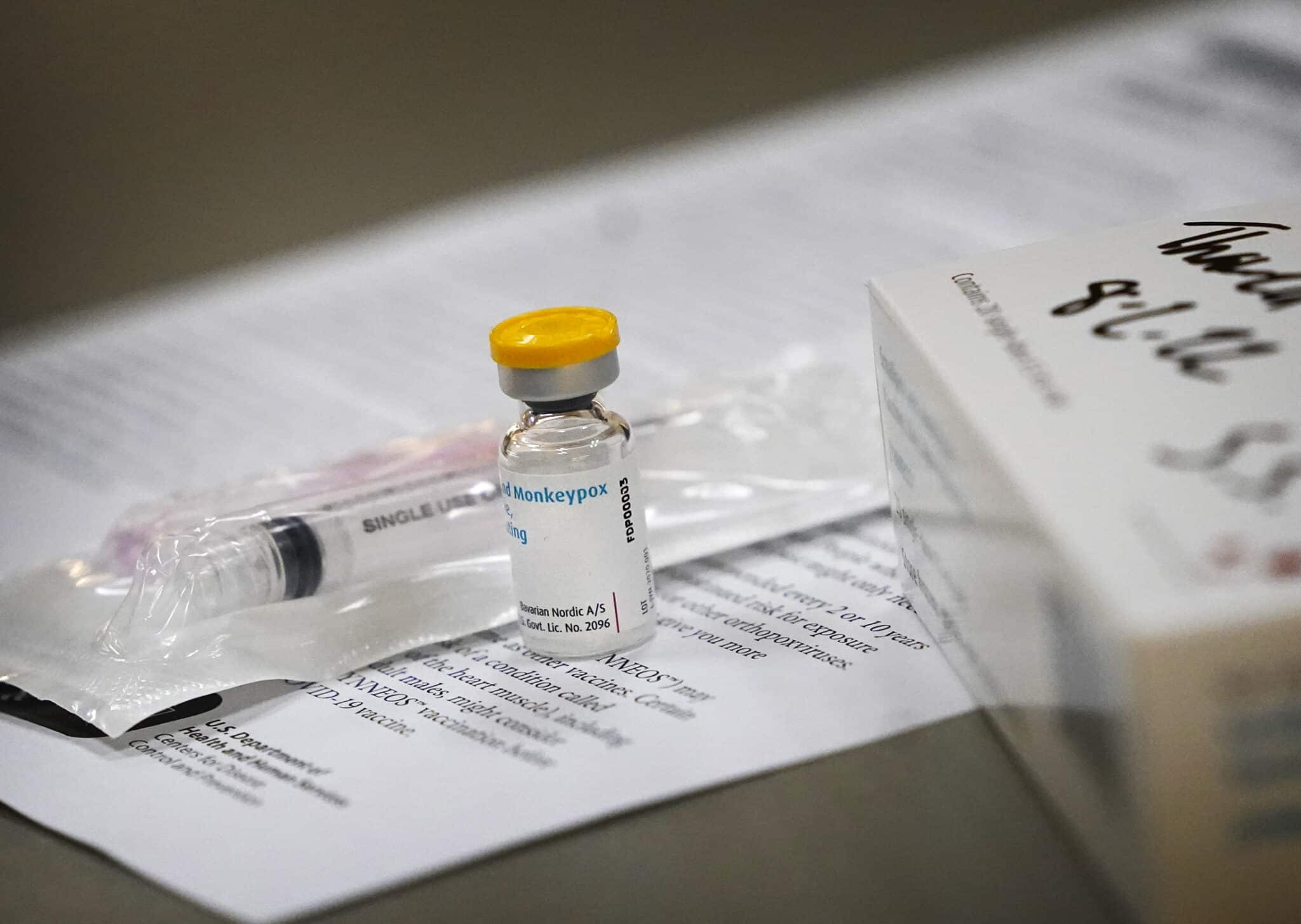

A vial of the monkeypox vaccine sits on a table during a media tour of the monkeypox clinic operations. (David Joles/Getty Images)

People who received the vaccine for smallpox in previous vaccination campaigns a few decades ago may still have some protection for this other orthopoxvirus which is monkeypox, however we know that the protection can decrease with time. At this stage we are suggesting that people who have had the smallpox vaccination in the past still continue to receive a single dose of the vaccine as a booster, and further evidence down the line is going to support the decision of whether we need to offer two doses or not.

If I’ve had monkeypox and recovered, am I then immune from contracting the virus for a period of time? If so, how long does immunity last?

We know that natural immunity is likely to be long-lasting – we don’t know how long it may last. So it may be that people can be reinfected, but that the specific timeframe in which that could happen is not established yet – like with COVID, when we took a while to understand that maybe after a few months, sometimes after a year, you can get COVID again. We still have not had that timeframe elapsing between the beginning of the outbreak and now so we don’t have all the information on that, but in general we think that the immunity for orthopoxviruses is of a longer durability than the immunity for example that we have for COVID or for the common cold.

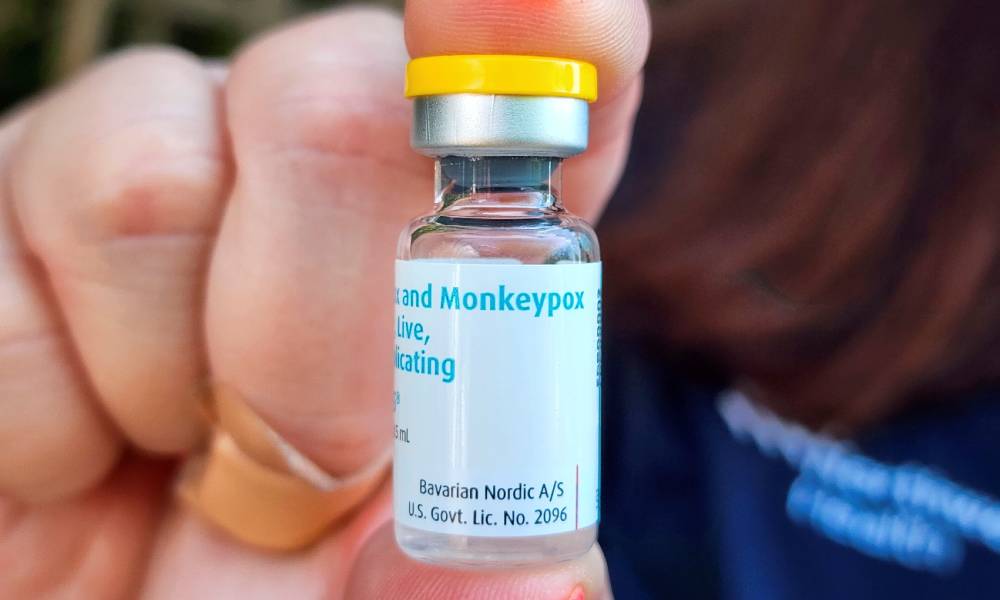

The UK is rolling out a vaccine for use against monkeypox. (Getty/PinkNews)

Is there any risk around getting a vaccine to protect against monkeypox around the same time as getting a COVID booster shot?

We have no reason to think that there is a cross reaction between both vaccinations. In essence both of them can be administered close to one another, so no, it’s not a contraindication.

Can face masks or other preventative measures we used with COVID be applied to monkeypox?

So transmission of COVID and transmission of monkeypox are different but there’s maybe a common area which is transmission through respiratory routes, especially when there’s direct and close contact. In that sense face masks may offer some limited protection to prevent that route of transmission, which is the respiratory route. That being said, the main route of transmission for monkeypox continues to be direct skin-to-skin contact, such as the kind of contact that happens during sex. In those settings, even with a face mask for example, people could get the infection. So face masks are not the most effective way of preventing monkeypox.

What do we know at the moment about the efficacy of this vaccine to protect against monkeypox?

We know this vaccine works to prevent some of the most severe infections and to support the control of the outbreak, but we know that vaccines are not a silver bullet. This means that even if you’re vaccinated you may be at risk of being in contact with infection and acquiring infection yourself, your symptoms may be milder, but you can still maybe develop infection and transmit it to someone else. So it’s really important that even if you’re vaccinated you’re on the lookout for any lesions in your new partners, any symptoms in your new partners, and any symptoms on yourself to make sure that if the infection does break through and does happen even if you’re vaccinated you can spot it and then stop transmission.

Is monkeypox likely to have a knock-on effect on public opinion of LGBTQ+ people, and if so, what can we be doing to combat that bias?

A lot of the stigma that LGBT people face is partly the cause of stigma related to infections. As a community we do still have the legacy of stigma related to HIV/AIDS and we still have stigma related to STIs and other infections. Monkeypox definitely just adds to that narrative where sometimes our communities are framed as the source of infection.

It’s really important that we communicate these things carefully and we achieve the right balance between an infection that is affecting us, but also an infection that has nothing to do with who we are. It’s just an infection that has been introduced into the networks that we exist in. So lots of anti-stigma work, making sure that we achieve balanced communication to ensure public health objectives are met, is really important to make sure we control the outbreak while we combat stigma from the root.

Monkeypox, a once rare virus, has spread worldwide in recent months. (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)

Men who have sex with men are being told to wait, in some areas, to be contacted about a vaccine. What do you do if your GP doesn’t know you’re gay?

It’s a difficult question but I think the best assessment you can do of risk is a self-assessment when you think about your own behaviour and your own risk. The best thing to do in those cases is to talk to sexual health services. Sometimes primary care may not be the place where you feel most comfortable talking about your risk or your behaviour, but sexual health services definitely have that expertise.

It’s also true that sometimes we may feel we are at increased risk, but we fail to realise that we exist in a larger cohort of people where some people may be at increased risk compared to us. Sexual health services will have that perspective, they will have that expertise, and when talking to people who work in these settings, they’ll be able to tell you, ‘actually you have less risk than you think you do, maybe you can wait for the vaccine while we’re prioritising the vaccine to those who need it the most’. It may also be the other case in which you’re talking to someone and they say, ‘actually you are right, you do need to be vaccinated as soon as possible. Please come forward, let’s book you in for an appointment’.

A monkeypox vaccine in a vial. (James Carbone/Newsday RM via Getty)

Can I catch monkeypox as a teenage girl in the UK and am I at risk?

Usually not. Of course we tend to say that infections are not tied to one sexual orientation, to one gender identity, or to one age group. These infections can affect everyone, regardless of what part of the community or society they are from. Someone with the characteristics you’ve mentioned, someone who is a teenager, will probably not be in the same networks, either social or sexual, of the people who are currently acquiring infection.

I think if anyone feels at particular risk for monkeypox regardless of their sexual orientation, their age group or their gender, they should be trying to contact someone in the health system to evaluate and assess that risk and to see whether they are eligible or not [for a vaccine]. There’s also a lot of information online that we’re putting forward really proactively to make sure people can also make that self-assessment and see whether they’re actually at risk or not.

Is it possible that prevalence of monkeypox is higher than we actually know at the moment?

The prevalence is the total number of people who have an infection at any given point in time. It’s almost impossible to have the best, accurate and precise measure of prevalence for any outbreak because we’re not currently testing people every day across the country regardless of any sexual orientation or behaviour. So the numbers that we report in any outbreak are always a bit behind what’s going on in reality, and that’s not a system failure, it’s just the nature of epidemiology and our systems for reporting.

The monkeypox infection has been detected largely among gay and bisexual men. (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty)

It’s more important to have a really robust assessment of the trends and how the outbreak is evolving and the trajectory and describing the people it’s affecting than having the most exact number at the exact time, exact hour, exact minute that we’re in. So yes, the numbers may not always completely reflect what’s going on, but it’s more about how we use that information to support the public and to control infections.

How safe is the vaccine? Are there any side-effects?

The vaccine has a good safety profile. There may be some side-effects related to pain at the injection site or mild, flu-like symptoms when you get the vaccine, but in general it’s a vaccine that is very safe, it’s unlikely to cause severe illness or sickness in people who have been vaccinated. In general from talking to many, many of my friends now who have been able to access the vaccine, their experience has been quite good and they’ve had minimal side-effects after being vaccinated.

Is there any risk of dying from monkeypox, especially for older people or those with underlying conditions?

We know that monkeypox can be a severe infection, especially for people who may be immunocompromised or people who may be of older age or very young age, so that’s why there’s so much importance given towards controlling the outbreak. It’s because it’s an infection that can have severe consequences.

Of course most cases will be mild or can be managed at home, but a minority of cases can progress into a very severe form of infection. Death has already been reported internationally and we know it’s a possible outcome of infection, which is why we’re doing our best to control it and to give people the right information so they can prevent infection.

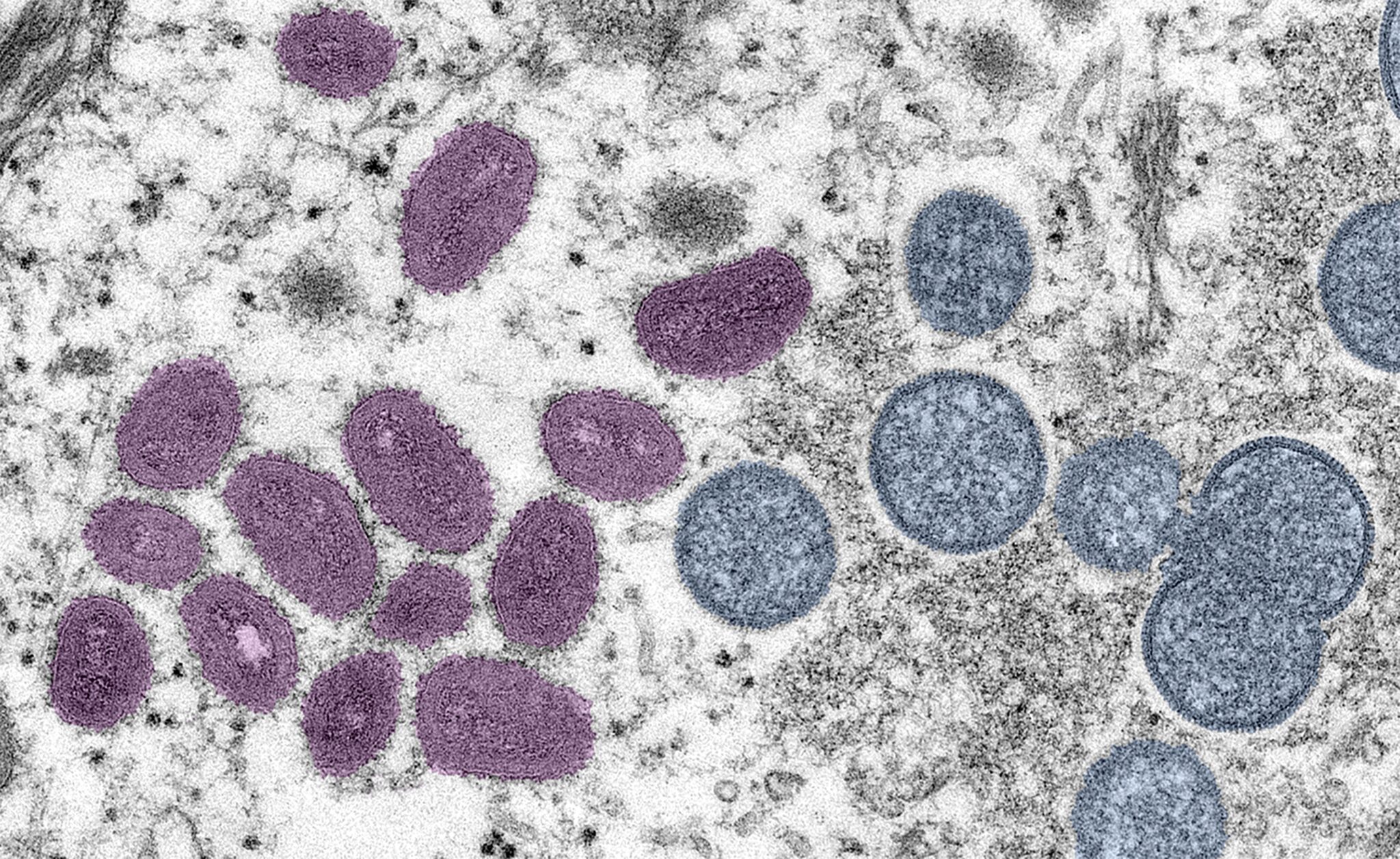

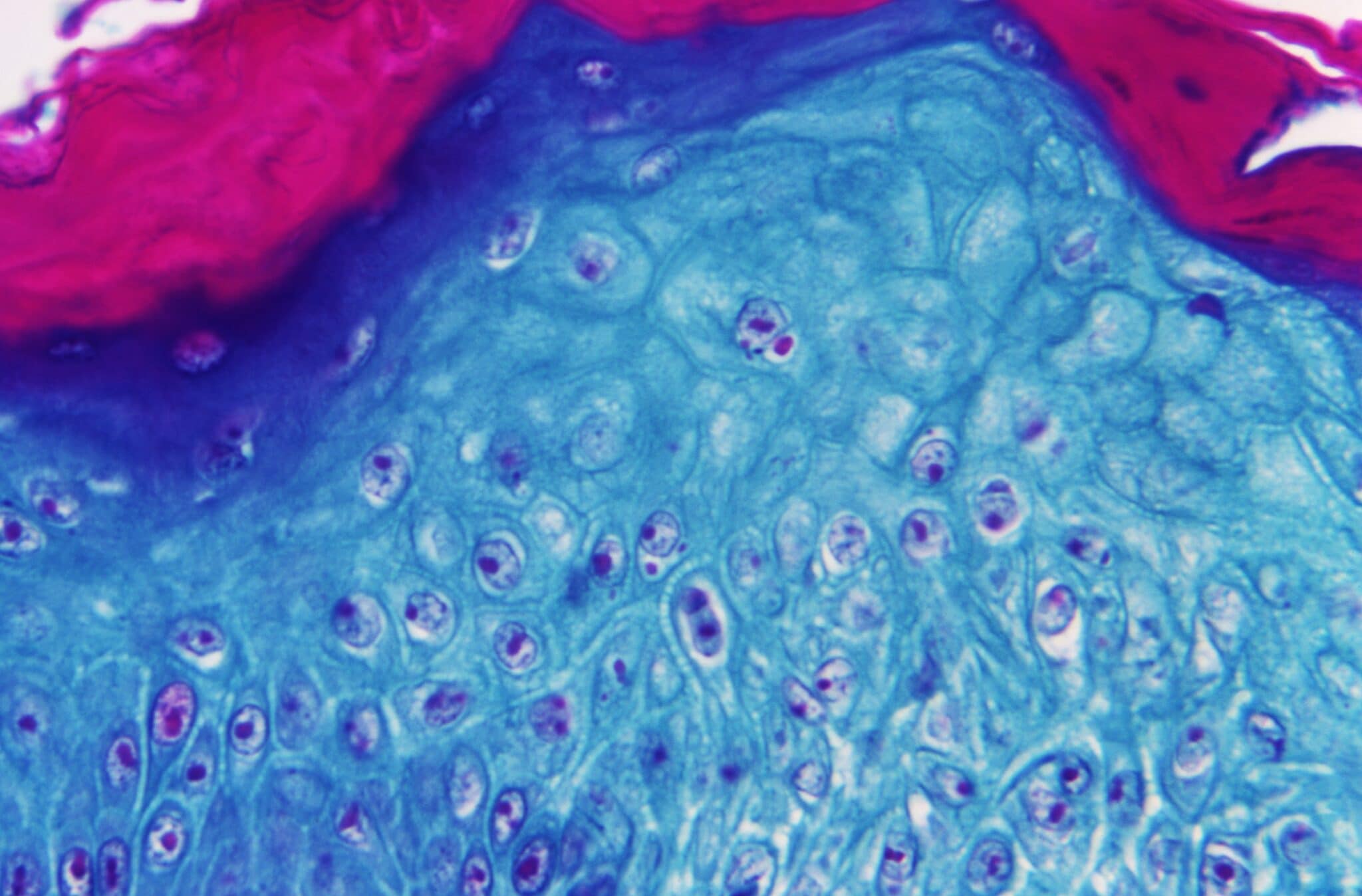

Monkeypox virus present in human vesicular fluid. (BSIP/UIG Via Getty)

What’s the best way to avoid contracting monkeypox?

The best way to avoid contracting monkeypox at this stage is making sure you’re being careful not to have sexual activity with people who have monkeypox symptoms, and that starts from thinking about ways in which you can engage in a conversation about monkeypox symptoms prior to having sex with someone. For example, you can ask someone, ‘have you had any unusual lesions or rashes on your skin? Do you have any pain near your genitals or have you had a fever recently, or noticed that your lymph nodes are enlarged? Are any of those things similar to what you have recently experienced?’. If they say yes to any of this you may choose to say, ‘maybe I’ll meet you at another time, maybe you should come forward and be tested’.

In general avoiding those exposures, avoiding those risks, is the best way to make sure you don’t acquire the infection. That of course doesn’t mean you should completely avoid sex. You can have sex with people who are feeling healthy, have no lesions, have no symptoms, and that will usually be better in the case of partners that you know, partners that you [can keep in] contact with, partners that you can talk to the next day and say, ‘hey, are you feeling alright? How are things since the last time we saw each other?’.

Microscope image of the monkeypox virus. (Getty/ Gado/ Smith Collection)

Am I at risk in public spaces?

Usually not, unless the public space is a place such as a venue where sex takes place. There are sometimes parks or cruising grounds where people will have sex with one another and they will be public spaces, but I’m guessing the question is more related to open spaces or spaces where you’re interacting with people in a non-sexual way.

In general the risk of transmission in those settings is very, very low. We have not seen after interviewing hundreds of cases any emerging patterns of transmission that suggest that being in public spaces with other people in a social way can be of any risk to you or your health, so we’re very much encouraging people to keep on enjoying the company of others.