How an ancient form of Indian dance helped filmmaker Shiva Raichandani understand their gender

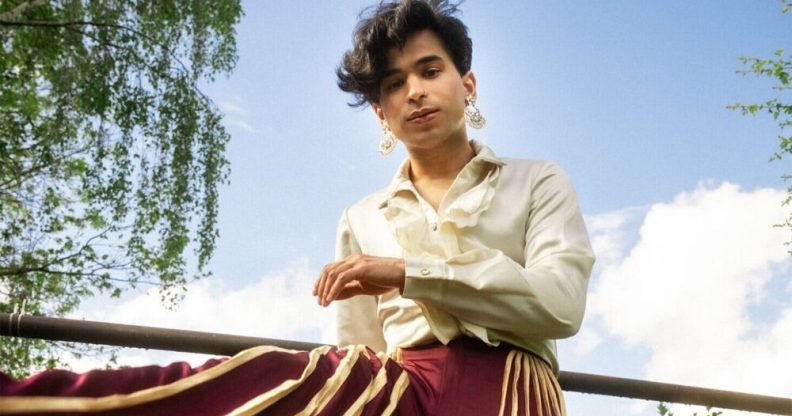

Shiva Raichandani. (Darius Shu)

Shiva Raichandani. (Darius Shu)

Shiva Raichandani is no stranger to forging an identity in different lands and cultures.

Born in Hong Kong, their childhood was spent in Indonesia, then adolescence in South India, before embarking on adulthood in the UK.

For most of their upbringing there was no space to discuss their queerness within the heteronormative and rigid family they grew up in. But that didn’t stop them.

“The beauty about South Asian culture is that there is a lot of room to play around with gender, especially through music and dance,” they tell PinkNews.

For Raichandani, Bharatanatyam, the oldest form of Indian classical dance, was the truest avenue for them to explore their relationship with gender-queerness.

“All my life dance has been such a beautiful outlet for me, thanks to my grandma, who’s also a dancer,” they explain.

“[In Bharatanatyam] you’re supposed to inhabit all of these different characters through different narratives. You could literally be the wind, a rock, an animal, a human, something completely inanimate, all within the span of one performance.

“Being able to walk into these different worlds, these different characters, these different possibilities, really helped me understand myself.

“The fluidity that dance offered really helped inform my own fluidity and allowed me to appreciate the expanse that comes with life, outside the rigid systems we have, not just the binary system but the pressures that society puts onto us.”

While dance gave Raichandani the tools to explore their gender identity it was not until later in life they discovered the words to describe it.

“For me, labels are a double-edged sword. Sometimes they can pigeonhole you, other times it can help you find community,” they say.

“Finding the right balance and living in the grey area of not being one thing or the other took a while to be comfortable with.”

Shiva Raichandani. (Shane Anthony Sinclair/Getty)

Outside of dance, Raichandani found “small pockets” of representation within South Asian culture. They found themselves in the song and dance of Bollywood actresses and the gender fluidity of Hindu deities. Although Shiva believes in the powerful impact of this representation, at the end of the day they say “no one can truly represent you but yourself”.

After moving to the UK, Shiva discovered the UK’s only pan-Asian drag cabaret collective, The Bitten Peach. Coming from a traditional dance background that was often structured, The Bitten Peach took the rulebook and “ripped it to shreds”.

They explain: “To enter this space where you’re queering it and bringing South Asianness to the forefront, but still challenging the toxicities outside and within the Asian communities? There was a very political nature to the art we were performing.”

It soon became the subject of their first documentary, Peach Paradise, commissioned by Netflix. “[The Bitten Peach] challenged me so much in how I approach art,” Raichandani said of creating the documentary, “simply because of how brave and how courageous they are in questioning the norm, and bringing in their own unique perspectives to their culture, and their artistry, which is great.”

They added: “When we talk about drag cabaret in the mainstream, the stories often centre white bodies and white narratives. We don’t get to really appreciate the grassroots talents that we have in the UK, especially Asian talent.

“So, it was a great way to uplift those voices by centring them and allowing them to represent themselves and to allow people to see that there are queer Asians out there in a profession that they don’t expect to see them in.”

While Peach Paradise does explore the racism and transphobia faced by the cabaret group, at its core it centres on queer joy. And this was very much the theme they took into their first feature film, Queer Parivaar.

Directed and starring Raichandani themself, Queer Parivaar is a fictional scripted musical that follows the couple Madhav and Sufi, whose wedding is gatecrashed by Madhav’s long-lost grandmother. It is a tender and joyful exploration of intergenerational South Asian culture and queerness.

In making Queer Parivaar, Raichandani wanted to bring together people from the South Asian queer creative community. People like Leo Kalyan, a gay British-Pakistani singer, “who’s absolutely incredible”.

“People like Asifa Lahore,” they continue, “the UK’s first out Muslim drag queen, and trans woman. DJ Ritu, who is an icon in her own right and one of the first pioneers of the queer South Asian music scene in the UK.”

Raichandani explains: “These two films have been really instrumental in shaping me as a storyteller and filmmaker, just simply because of how different experiences were, but also how both of them brought queer Asian talent to the forefront in a way that is rarely done.”

Shiva Raichandani says queerness and gender nonconformity within South Asian communities has always existed. (Gareth Cattermole/Getty)

Looking forward to the future of queer South Asian art, they say: “I feel like a lot of our stories, especially trans and non-binary stories, tend to come from sadness and death and violence and trauma. While all of that holds true, there’s so much room to showcase more.

“Show us happy, show us thriving, show us successful, show us in love, show us jealous, show us mundane, show us boring. We are different people. Show us the complexities that come with it.”

Raichandani urges the TV and film industry to not only “hire, fund and invest in South Asian queer talent” but to allow them to tell their own stories. “There’s so much depth and richness in the South Asian queer experience that deserves to be seen,” they say, “and that can really challenge the mainstream understanding of queerness in itself.”

“Because queerness and gender non-conformity within South Asian communities has always existed. We’ve always been here.”

As our chat comes to an end, Raichandani reflects on their journey with their gender identity: “Someone once said, there are as many gender identities as there are humans, because your gender is just your own. I’ve found a lot of comfort in that.

“We don’t offer ourselves enough grace and empathy and kindness, to experience change, to question what doesn’t make us comfortable, and be OK with not knowing what is comfortable.”

They continue: “It might seem scary, but to me, there’s so much joy to be found in the unknown sometimes. To know that you could be anything, you could express yourself however you want to. Sure, there are societal and legislative limitations or constraints but on a core level, there is no restriction.”

Although Raichandani stresses they have not yet reached a state of complete gender euphoria, they no longer feel they have to prove their gender to anyone.

“My gender is very undefined in that sense,” they say, “it’s taken a while to get to that point because the way in which we talk about trans and non-binary identities in Indonesia is very different from India, and then different from a Western context.”

As Raichandani looks forward to future projects, with another documentary coming out later this year, they sum up what being South Asian and queer means to them.

“A celebration of life,” they say after some reflection. “There’s so much vibrance and joy to be found in being South Asian and the expanse that queerness offers put into perspective how, in so many ways, we celebrate all that life has to offer.”