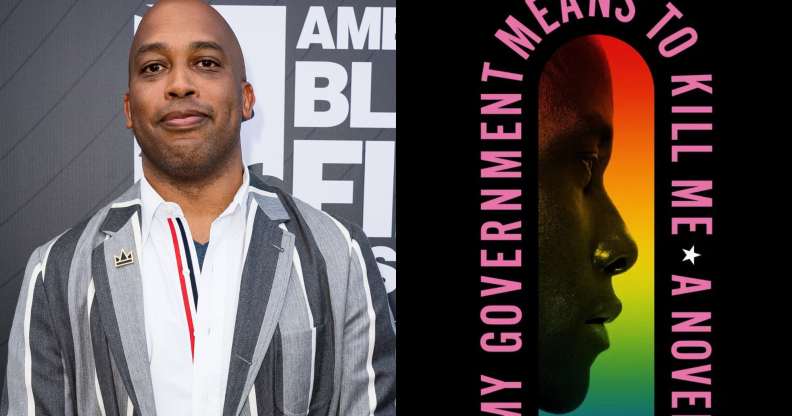

Bel-Air writer Rasheed Newson tells true story of heroic, revolutionary AIDS activists in new book

Rasheed Newson’s new novel is titled My Government Means To Kill Me. (Jason Koerner/Getty)

Bel-Air writer and executive producer Rasheed Newson on his powerful new novel, My Government Means To Kill Me.

Diving deep into a world of activism and AIDS advocacy, My Government Means To Kill Me gives a glimpse into the strength and resilience of marginalised queer communities, with fictional characters colliding with real-life figures like civil rights hero Bayard Rustin.

It follows the story of Trey, a 17-year-old gay Black man trying to navigate New York during the mid ‘80s.

Through Trey’s eyes we see the formation of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), founded by playwright and gay rights activist Larry Kramer in 1987. It depicts real, historical events, including the speech Kramer gave in 1987 that led to the forming of ACT UP, but also has its own story to tell.

Much of the story takes place in and around Mt Morris Baths, a bath house which was a central hub for gay African-American men and the scene for both Trey’s political and sexual exploration.

Larry Kramer at Village Voice AIDS conference on June 6, 1987 (Catherine McGann/Getty)

What was your process for researching the book? Was there anything that caught you by surprise?

In a weird way I have been doing research my entire life. I’ve seen every documentary from How To Survive A Plague to The Celluloid Closet. But the thing I found the most helpful when it came to getting the voice of people from time were the oral histories and videos. I would do chores around the house, and listen to Bayard Rustin, or listen to Larry Kramer talking about his life.

The thing that most shook me up was the realisation that for a lot of people, AIDS came into our consciousness when the New York Times wrote about it in 1981. In retrospect, people discovered that they had AIDS, or had met people who had died of AIDS, going back into the 70s.

I received an email from someone who read my book and they had participated in a Hepatitis B study in 1979. Their sample was preserved and when someone ran a blood test on it, they contacted him in 1985 and told him he was HIV positive.

It’s only recently we have started to see new narratives about AIDS that amplify marginalised voices in the community, like the Channel 4 series It’s A Sin. What does it mean to you to contribute to that?

It feels good to expand our understanding of this time period, when it started, who was involved, who was affected and who came to the front lines. I loved It’s A Sin because it had the female character [Jill] who became a caretaker.

Women are typically written out of the story as well. It’s always a circle of white friends who are all gorgeous, all thin, all model handsome, and they don’t know any other body types or races or women. Lesbians came to save the gay male community and quite frankly, we had not been very nice to them before then.

Rasheed Newson. (Christopher Marrs)

What was your favourite part of the novel to write?

I really enjoy Trey’s relationship with the men in his care. He doesn’t make anyone feel like a victim or a charity case. He allowed those men their dignity.

Then there are the scenes in the bath house. It was fun to have a gay character who struggled with homophobia but largely was comfortable with their sexuality. He could walk around a bath house proud and having fun and feeling – quite frankly – powerful, because he was desired. Sex finds a way and so I thought it was an honest part of the book.

How do you strike that balance between writing the joy that comes from being yourself and the hardships that come from being a part of the queer community?

It’s something I’ve had a lot of experience, especially when I was younger, as an advocate and protester. People have this misconception that when you’re doing that sort of work you are dour or humourless. But some of the funniest people I know are some of the fiercest advocates I know. Having a sense of humour is what sustains you and being able to find joy is what keeps you from going mad.

What are the parallels between America now, and America in the ’80s, if any?

In terms of progress, the thing I have realised is that political gains come and go, as we saw with the reversal of Roe v Wade. Sure, at this moment we have gay marriage but we’ll see how long we keep it. My husband and I have adopted two children and not being a legally married couple would make adoption very difficult, if not impossible in some states. It makes me sick to my stomach.

Rasheed Newson. (Christopher Marrs)

We are seeing book bans in America that overwhelmingly target queer stories, is that something you considered before publication?

Book bans are ridiculous but it didn’t affect me in the sense that I was always going to write what I wanted to. You don’t know what the political wind is gonna be when you write something. Nobody writes a book hoping it’ll get banned but I didn’t think about it either.

My concern was for people who lived in the time period I was writing about. I wanted to get this right for the queer people who did advocacy work and were members of ACT UP. I wanted it to capture the mindset and the spirit and the heart of what they did. It’s been very gratifying to hear from people who have lived through it to say ‘this took me back’.

What do you hope people take from this book when they read it?

I hope the book is a call to action. Signing petitions, retweeting and donating his money is nice but showing up is best. Protest, volunteer, give your time.

I guess my last question is, are you looking forward to shooting season two of Bel Air?

Oh, absolutely. It is much more nerve wracking to have a first season where you’re not sure if the audience is going to show up. Going into the second season we know how this works. We know that there’s chemistry.

In season two we get to expand the family a little bit, bring in some more characters I think people will remember from the first season, and we also get to continue the game of planning easter eggs for viewers of the original series to spot. So we’ll see.

You can buy My Government Means To Kill Me by Rasheed Newson here.