Tories should worry about fixing trans healthcare, not going to war over gender recognition

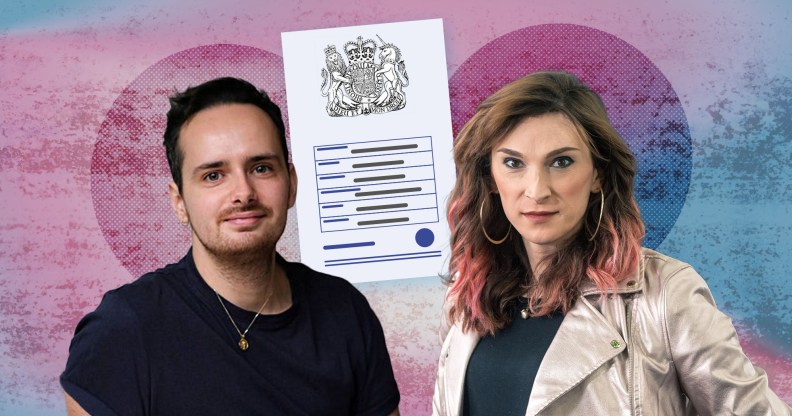

Harry Nicholas and Juno Dawson both went through the GRC process so that they could marry as their true gender. (Sophie Davidson/Getty)

Trans folk are “perplexed” as to why the UK government is fighting Scotland’s proposed gender reform instead of tackling the trans healthcare crisis.

Rishi Sunak is on course for a historic clash with the Scottish government over the latter passing a bill to make it easier for trans people to gain legal recognition of their gender.

In order to change the gender marker on their birth certificate, a trans man or woman must apply for a Gender Recognition Certificate, or GRC (non-binary people have no path the legal recognition as things stand). Under UK law, they must submit evidence including a medical diagnosis and proof they’ve lived as their true gender for two years.

After the Tories ditched plans to streamline the process, Scotland took up the mantle. It passed its own reform bill in December, removing the need for a diagnosis and lowering the age limit to 16. The Tories are now threatening to block the bill from becoming law in an unprecedented intervention.

Author Juno Dawson recalls getting a GRC in 2018 because it was likely she would get married to her now-husband, and she “wanted to be able to get married as a woman”.

“Up until that point, for the first five years of my transition, there wasn’t a burning need for me to have one,” Dawson says, explaining that she was able to get a driver’s license and passport with a female gender marker without a GRC (they’re only needed for birth, death and marriage certificates).

“So actually there were more important things for me to get – other forms of ID.”

For Dawson, that’s why the “fuss around gender recognition and [the] Gender Recognition Act is so perplexing”, especially as “so few trans people” get a GRC.

In 2021, after the Tories ditched plans to streamline the process, official figures stated that fewer than 6,000 people had obtained a GRC. The 2021 census put the size of England and Wales’ trans population at 260,000 – though only 96,000 identified with a binary gender, the only options available on GRCs.

Dawson describes the process as a “huge admin headache” that involves providing a “paper trail” of documents which are sent before a UK-wide panel.

UK law demands a diagnosis of gender dysphoria – something Scotland is attempting to drop. To get a diagnosis, a person must see an NHS gender specialist.

Dawson says this is the “really difficult bit” because it’s oftentimes “being massively held up by NHS waitlists”, which can stretch for years.

Currently there is just one specialist gender and identity service for the whole of England and Wales – soon to be replaced with two regional pilot schemes – and overlong waiting times have been described as life-threatening.

“So actually this whole argument comes down to NHS waiting times because you can’t apply for a [GRC] until you’ve been through the NHS system, which at the moment will take a trans person 3 to 4 years plus,” she adds.

“So it’s a double bind. If we were to simplify the legal process or if we were to allow a GP to sign off on it rather than a specialist, it would mean that actually trans people could get their paperwork in order faster which would mean there were far less likely to be people claiming to be trans when they weren’t – that doesn’t happen anyway – but I think if we were to simplify the process of gender recognition, it would I think put peoples’ minds at rest.

“The only people who are applying are genuine trans people who just want to live their lives.”

Like Dawson, Harry Nicholas decided to apply for a GRC when he contemplated marriage with his partner.

“I didn’t want, when that moment happened, of him potentially proposing to me from my first thought to be, ‘I don’t want to be his wife’,” Nicholas says. “I didn’t want my first thought to be, ‘I have all this admin to do’.”

Nicholas, also an author, quips getting a GRC was the “easiest” stage of out the “whole process of transitioning” – but only because of how difficult it can be to access gender-affirming healthcare.

“Just because I said this process was the easiest out of the whole transition, that isn’t a reflection on how easy the process is – that’s a reflection on how bad the rest of trans services in the UK,” he says.

“The fact I felt it was really quick that the GRC process took six months, that isn’t quick, that’s in comparison to being on a four-year waitlist.”

Nicholas says misinformation about what the GRC does is “really frustrating” – opponents of reform often suggest it will impact access to single-sex spaces, but this has never been contingent on having been through the GRC process.

Ultimately, the issue is “low on [the] priority list” for the trans community given the dire state of services, Nicholas says. He’d rather see more people advocating for climate change reform, supporting nurses and speaking out for LGBTQ+ asylum seekers or trans people seeking safety abroad.

“I think trans healthcare is the first and foremost thing that we’re looking at, and that would make the [GRC] process later on easy,” Nicholas says.

“I don’t think actually it’s been trans people asking for this. It’s important, but I don’t think, if I had a choice of what needed to be put forward, it would be legal [gender] recognition especially because it doesn’t include non-binary people.

“It doesn’t include the nuance in our experience.”