The Metropolitan police found to be corrupt in the 1970s – and it seems little has changed

Several inquiries have proved the Metropolitan Police is inherently corrupt. (Getty/Metropolitan Police)

Several inquiries have proved the Metropolitan Police is inherently corrupt. (Getty/Metropolitan Police)

A newly released report into the Metropolitan Police has revealed damning evidence of corruption – and it seems little has changed in 50 years.

Baroness Casey’s review, released yesterday (21 March), shows that London’s police force is riddled with misogyny, racism and homophobia.

The review was commissioned in 2021 following the rape and murder of Sarah Everard by serving firearms officer Wayne Couzens.

Shocking evidence of serving police officers committing forms of harassment and assault, including sexual harassment, has revealed just how institutionalised the problem is.

Additionally, a survey commissioned for the review found that 19 per cent of all lesbian, gay or bisexual respondents from within the Met have directly experienced homophobia – with 14 per cent of those saying it happens every week.

Prior to this, Met officials claimed that problems stemmed from “a few bad apples”, but previous reports dating as far back as the 1970s have proved that the force has been this way for decades.

Operation Countryman

In 1978, an investigation into police corruption, known as Operation Countryman, was commissioned. It ran until 1982. Several rural police departments, including Hampshire and Dorset, were given the task of investigating the Met.

They found officers were routinely taking bribes from criminals to help mitigate charges against them.

While the investigation initially looked into the City of London Police department, it spread to the Met.

Serving police officers were believed to have been taking bribes in exchange for prior warnings of raids, the fabrication of evidence and dropping charges.

The problem was so prolific that Arthur Hambleton of Dorset Police, who led the inquiry, told the press that he believed the corruption had spread to “senior officers up to a certain level”.

He said: “I’m not speaking about the very senior officers of Scotland Yard, I’m talking about the senior operational officers. This very, very serious problem has been, and probably still is, in the Metropolitan Police.”

At the end of the investigation, Hambleton admitted he was “absolutely staggered” by the extent of institutional corruption suggested in his report.

He also admitted that officials, including the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) Sir Thomas Hetherington, who died in 2007, had attempted to disrupt the investigation on a number of occasions.

Although eight officers were prosecuted, none were convicted of a crime.

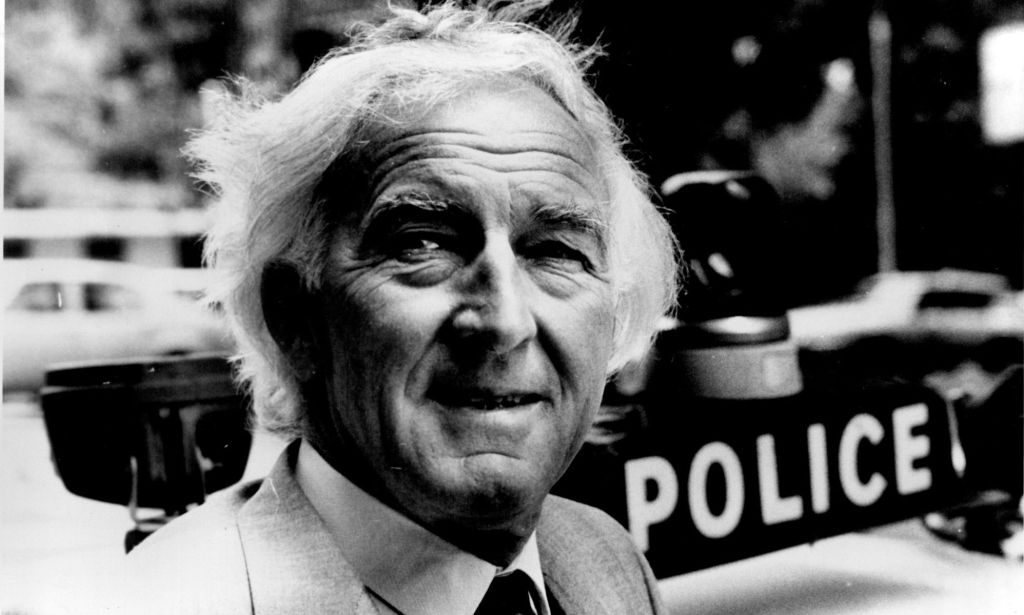

In a documentary aired in 1982, shortly after the conclusion of the investigation, former Met Police deputy assistant commissioner, John Alderson, corroborated the corruption within the force.

“I’m sorry to say, my impression of the state of corruption these days is in spite of the work that [1970s Met Police commissioner] Robert Mark did, it’s more institutionalised than it was,” Alderson said.

“By institutionalised, I mean, formerly, it was in pockets here and there but I think there are now certain sections of the CID – certain cohorts, if you like – where it’s accepted. It’s just become, for some of them, a way of life.”

Operation Tiberius

In 2001, an internal inquiry – Operation Tiberius – again looked into corruption within the Met.

A report was written two years later but wasn’t made available to the public until 2014 after it was leaked to The Independent.

It outlined that the force was being “infiltrated by organised crime gangs” that would exploit legal loopholes to further criminal ends.

Evidence of jurors being paid off by senior members of the force – who were suspected of associating with “Britain’s most notorious criminals” – was just one of the shocking conclusions.

“The true assessment of the damage caused by these corrupt networks is impossible to make at this stage, until further proactive scoping has been undertaken,” the report read.

Statements uncovered in the report found junior officers felt hesitant to “carry out an ethical murder investigation” due to fears of it being compromised.

Additionally, several criminals are thought to have been wrongly acquitted, effectively buying not-guilty verdicts from jury members.

Homophobia and racism allegations

If internal and commissioned investigations finding similar levels of institutional corruption aren’t enough, there are several instances of Met Police failings that are plain to see.

One of the more recent high-profile cases of discriminatory behaviour involves the mishandling of the investigation into the murders of four men by “Grindr Killer” Stephen Port.

Port is known to have killed at least four young men – Anthony Walgate, Gabriel Kovari, Daniel Whitworth, and Jack Taylor – over the course of 16 months after he met them on Grindr between 2014 and 2015.

After an inquest into the murders in 2021, the Met Police was accused of institutional homophobia due to their apathy regarding the investigation.

Reviewers at the Independent Office for Police Conduct found evidence that the investigation was “materially flawed,” while other reports detailed a “lack of professional curiosity”.

A spokesperson for the legal team representing the families of the murdered men said that they believe the case was treated without professionalism because of the victims’ sexuality.

“They’ve always wondered about whether there would have been a different outcome if the police had investigated Port properly and taken their concerns seriously and if their boys hadn’t been gay,” the spokesperson explained.

Another notorious instance was the murder of private detective Daniel Morgan in 1987.

Morgan was found dead in a south London car park after having been attacked with an axe. Despite several Met Police investigations, no one has been convicted of a crime.

In response, Morgan’s family accused investigating officers of corruption, saying they believed the lack of leads to be part of a cover-up.

An inquiry, which came to a conclusion in 2021, found that the Met Police is “institutionally corrupt,” with a review panel saying that the force prioritised its reputation above weeding out corruption.

“The Metropolitan Police were not honest in their dealings with Daniel Morgan’s family, or the public,” panel chairwoman Baroness O’Loan said. “The family and the public are owed an apology.”

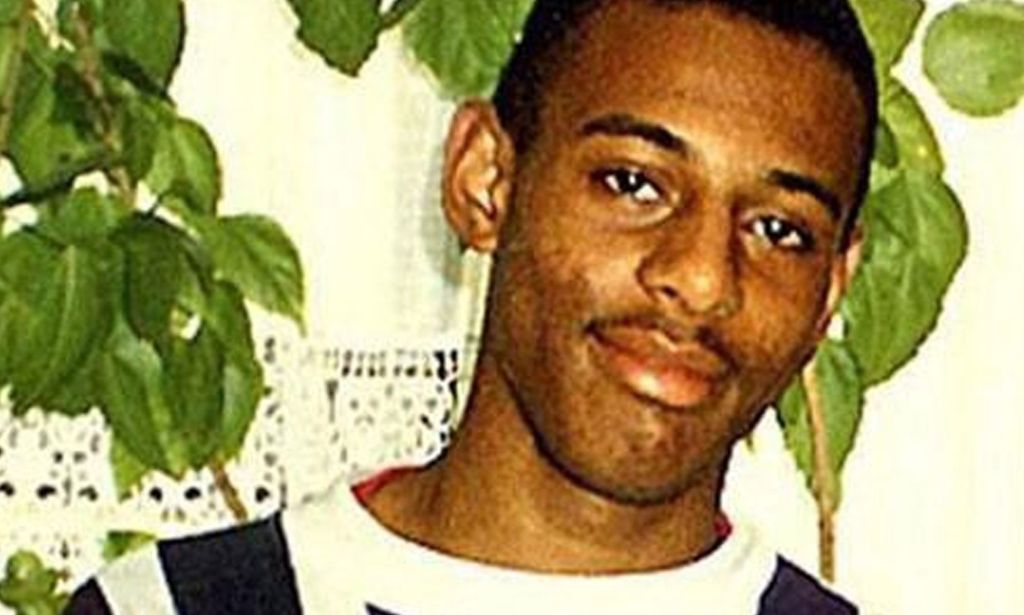

Finally, one of the most high-profile examples of institutional discrimination came in the case of the murder of Black British teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993.

Lawrence was stabbed to death in a racially motivated attack near West Hall Road in Eltham, London.

The following investigation and treatment of the case brought criticisms of institutional racism against the Met.

His family believe that not enough was being done to apprehend the killers because Stephen was Black, and began campaigning for justice.

In 1997, home secretary Jack Straw announced an inquiry into the Lawrence scandal, led by Sir William Macpherson.

The subsequent Macpherson Report essentially found that the Metropolitan Police are “institutionally racist” and that more needed to be done to prevent further harm.

He explained that, at its heart, the force holds a “collective failure” to provide their duties “through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people”.

Following the Baroness Casey report, Stephen’s mum, Baroness Lawrence, said the Met is still “rotten to the core”.

The investigation and subsequent inquiry remain a grim reminder that the Metropolitan Police is, and has predominantly been, an institutional hotbed of corruption and bigotry.