Nigerian author Arinze Ifeakandu stuns with short stories of queer intimacy

Arinze Ifeakandu speaks to PinkNews about his debut short story collection. (Bec Stupak Diop)

Arinze Ifeakandu speaks to PinkNews about his debut short story collection. (Bec Stupak Diop)

“My entire thinking is deeply Nigerian.” Acclaimed author Arinze Ifeakandu sits down with PinkNews to discuss his queer short story collection, anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and the enduring power of community.

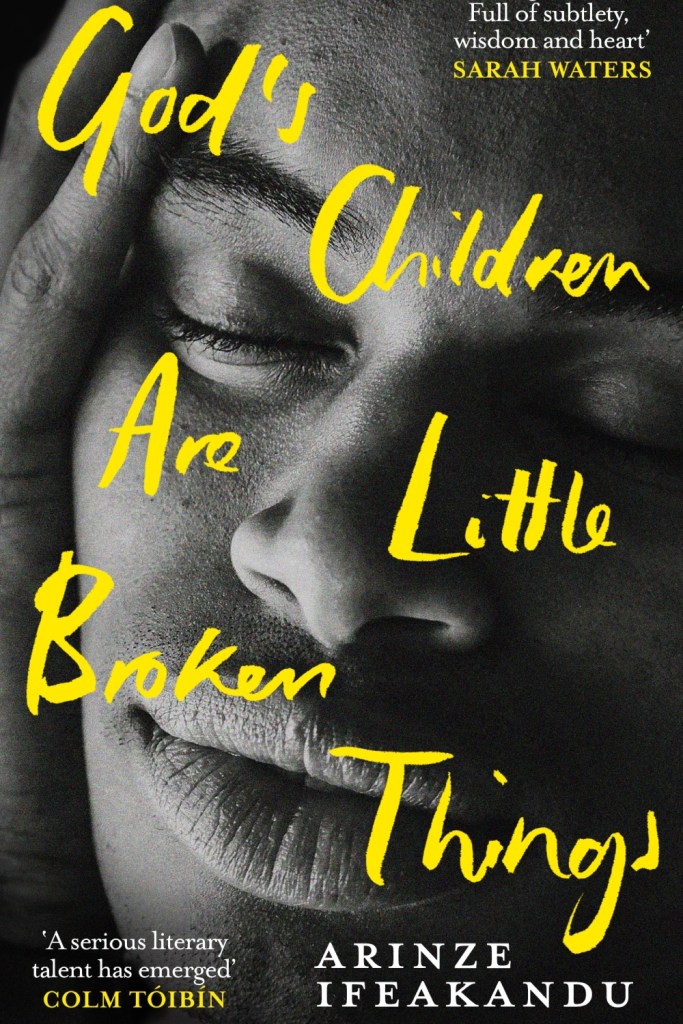

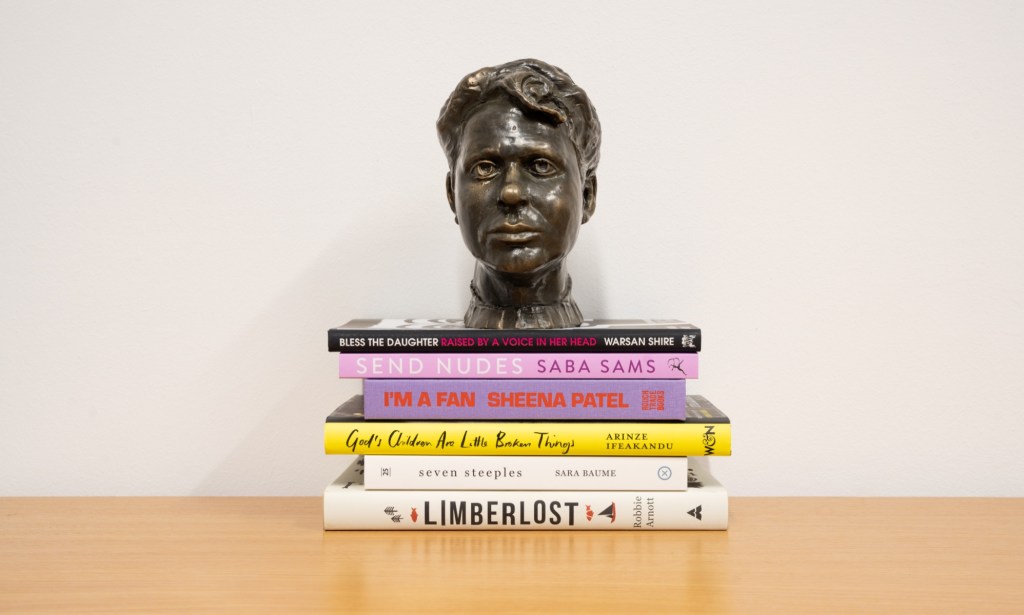

First published in the UK in July 2022, Ifeakandu’s stunning debut, God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, has been shortlisted for the prestigious Dylan Thomas Prize 2023, and praised by fellow authors and critics alike.

The prize nurtures international literary excellence from young writers and is the one of the foremost UK literary prizes, named after Swansea-born poet Dylan Thomas. There can be no doubt as to why Ifeakandu made the cut.

Over the course of nine short stories, the author offers the reader an intimate and tender portrayal of queer love and its universality. He dips into themes of queer male sensuality, grief, loneliness, self-discovery and the reality of being gay in modern-day Nigeria.

It is perhaps best summarised by the book’s description, which reads: “Generations collide, families break and are remade, languages and cultures intertwine, and lovers find their ways to futures from childhood through adulthood, on university campuses, city centres, and neighbourhoods where church bells mingle with the morning call to prayer.”

The collection is a true ode to resilience and it is this feeling that first drove Ifeakandu to put pen to paper in 2014, after Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act was signed into law in January of the same year.

‘I wanted to see two boys fall in love with each other’

The draconian law not only forbids same-sex marriage, but targets any co-habitation between same-sex couples and any “public show of same-sex amorous relations”. Punishment ranges from 10 to 14 years in prison, although some men have even been sentenced to death by stoning in recent years, under different legislation.

“I remember exactly where I was when I heard the news and I remember my exact reaction,” Ifeakandu reflects. “There were feelings of despair but also a quiet resistance.

“I thought, ‘you can’t tell us what to do’. There was a deep sense of survival but also compromise behind a lot of these stories. I want to live my life but survive in society.”

Ifeakandu has created a “fantastical world” with his fiction. “I wanted to see two boys fall in love with each other, explore how they talk, who they are, their dreams and desires,” he explains.

Over the course of eight years, as he furiously penned his work, he saw a movement developing within the LGBTQ+ community in Nigeria, to speak truth to power and effect positive change.

“I’ve always been optimistic about things,” Ifeakandu says. “Right after the law was made, people started publishing blogs, forming intentional communities, publishing anthologies.

“I met people whose parents know their boyfriends. It is a certain unwritten rule to not say you are gay in public but in private, there is a movement. It means a lot of people are choosing the happiness of their children over amorphous stupid ideas.”

Ifeakandu is keen to stress that Nigerian culture is not homogenous. After growing up in Kano in northern Nigeria, Ifeakandu moved eastern Nigeria to study, a transition that gave him an insight into the boundless diversity of the nation, across ethnic groups, religion and dialect.

On moving to the US in 2017 to study for his master’s degree at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Ifeakandu was struck by the stark social differences from his country of birth. He is now undertaking his PhD at Florida State University.

“America is a deeply individualistic society,” he says. “One of my deepest frustrations with Nigeria is the lack of privacy but when I travelled and realised nobody cared about each other, I realised I prefer Nigerian culture over this deep sense of isolation.”

The importance of community is a strong thread that runs through Ifeakandu’s stories.

‘I will be OK as long as I have real love for myself and the people that I call my own’

“My fellow Nigerians, people from my community, have told me it felt good reading stories that reminded them of their own time at university, or the days of figuring themselves out,” Ifeakandu tells PinkNews.

Placing this in the context of queer male relationships is particularly revolutionary for an author who never saw that kind of representation when he was growing up.

He says: “I had deep physical affection with my family, my friends, but as soon as that was turned sexual in a queer relationship, suddenly it was something else.”

It was this lack of representation that “drove me to my desk to begin to write queer stories”, Ifeakandu continues.

However, he holds hope for future generations, as Nigeria experiences an “explosion” of LGBTQ+ literature.

Ifeakandu’s work joins a thriving queer literary community, with notable works including Chinelo Okparanta’s 2015 novel Under the Udala Trees and Nnanna Ikpo’s 2017 novel Fimi sile Forever.

There is still a long way to go when it comes to LGBTQ+ rights in Nigeria, but over the years of pouring his soul into this collection, Ifeakandu has found a sense of peace.

“There are times in which I might not recognise myself but I will be OK as long as I have real love for myself and the people that I call my own,” he says.

And he hopes to pay this forward with his work. When asked what he wants readers to take away from his book, Ifeakandu says: “I just want them to feel what they feel.

“Hopefully, when they read it, they will just allow themselves to experience it as it is.”

You can buy the Dylan Thomas Prize-shortlisted collection God’s Children Are Little Broken Things here.