The long history of drag – from vaudeville to Reagan – and why right-wing outrage is nonsense

Robin Williams is one of the many American icons to perform as another gender. (Getty)

Robin Williams is one of the many American icons to perform as another gender. (Getty)

As Republicans try to ban drag queens from performing for children, it’s worth remembering that drag reaches far back into America’s history

The US is facing rampant gun violence, hate driven by ignorance, a growing climate crisis and increasing levels of inflation. Yet, among all the issues facing Americans right now, Republicans have decided that drag is one of the most pressing, dangerous issues in the land.

Tennessee passed what amounts to an all-out ban on public drag shows – though there’s a legal challenge in the works to overturn it – and similar anti-drag legislation is brewing in other states.

LGBTQ+ and trans advocates have warned these bills are just another means to attack queer folk and could be used to criminalise gender non-conformity.

Conservatives claim it’s about protecting children, but that ignores a few basic facts: that drag poses no inherent threat to children, that there are family-friendly forms of drag just as there are family-friendly forms of every entertainment, and that drag has been part of the fabric of society for centuries.

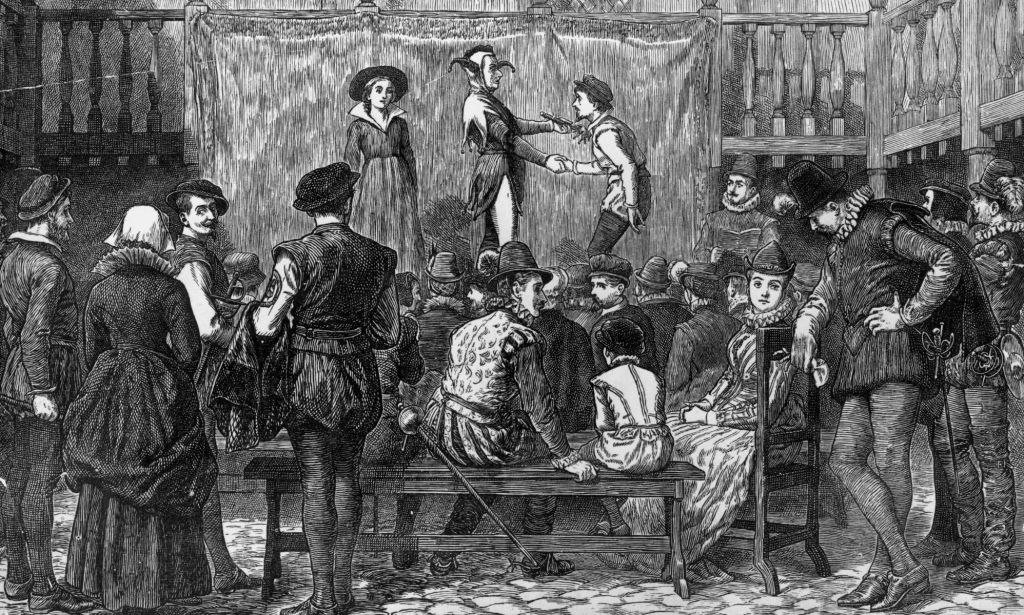

Actors have dressed and performed as other genders for as long as theatre has existed. While drag is a distinct style of performance with strong ties with the LGBTQ+ community, theatre throughout history laid the foundation on which modern drag exists.

In ancient Greek theatre, female roles were played by men. In Western opera, there are traditions of singers being cast as any gender.

Kabuki – a Japanese traditional theatre form, which originated in the early Edo period – originally had both men and women acting in plays. But eventually, women were banned from performing so men took on all roles, a tradition that remains to this day.

When William Shakespeare’s plays hit the stage, male actors would often dress as another gender to keep the story going.

The term “drag” is believed to have originated in 19th-century English theatre slang, originally referring to describe men who performed wearing what was considered traditionally to be women’s clothing.

Supposedly, the word referred to how the clothing the men wore to play female characters would drag along the floor.

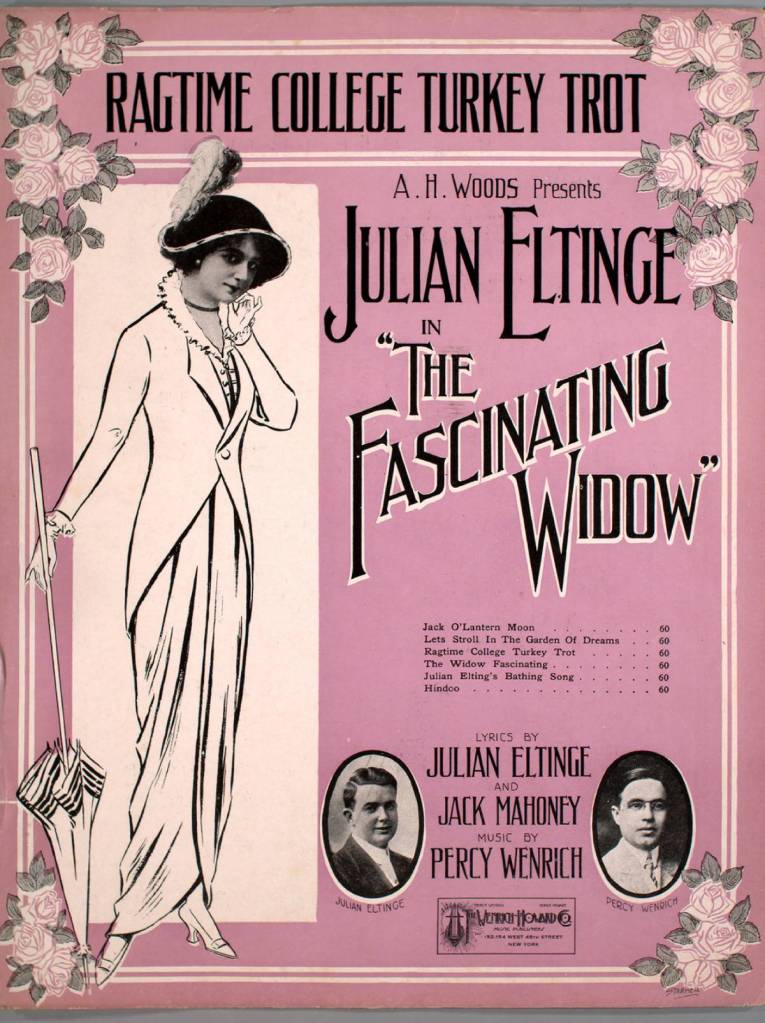

In the early 20th century, the highest paid actor in the US was a drag queen

As time went on, drag became more about the individual than the theatrical performance in which they took part.

Vaudeville, which was especially popular in the early 20th century, is a type of entertainment consisting of short acts such as comedy, singing and dancing – some of the tenants of modern drag performances.

One of the biggest stars of this period was Julian Eltinge, a pioneering American drag artist, or female impersonator as they were known at the time. Eltinge was at one point the highest paid actor in the US.

The actor fell from grace as vaudeville became less popular and crackdowns on cross-dressing in public prevented Eltinge from performing in costume.

Though, that wasn’t the end of drag. There was a tolerance and even celebration of drag in the US during the 1920s and 30s, known as the ‘pansy craze’.

Ronald Reagan once starred in a film that featured drag

Soldiers creatively kept boredom at bay by performing in drag through various parts of history, but particularly during WWII. It was during this period that the propaganda/fundraising play turned film This Is the Army was born.

The play was produced by the US Army on Broadway in 1942 with a cast of US soldiers and music and lyrics by Irving Berlin for the benefit of the Army Emergency Relief Fund. It was later turned into a film that was immensely successful and won an Oscar in 1944.

This Is the Army featured actual soldiers dressing in drag for multiple scenes, for crowds of all ages. And not one but two Republican politicians were in the movie: future president and governor of California, Ronald Reagan, as well as George Murphy (eventual senator for California).

Drag is associated with the queer community but remains a mainstay of pop culture

Conservative hypocrisy will always find reasons why it’s OK for Republican politicians and far-right pundits to enjoy actors performing as the other gender in film and TV, but rally against professional queens doing story times for kids.

People have been entertained for decades by characters like Robin Williams as Mrs Doubtfire, the various Monty Python performers, Jamie Farr on M*A*S*H, Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie, Tom Hanks in Bosom Buddies and even cartoon icon Bugs Bunny.

And lest we forget the bevy of films and plays centring on drag like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, Kinky Boots and Everybody’s Talking About Jamie.

Drag featured heavily in the history-making 1990 drag ball documentary Paris is Burning.

Paul O’Grady shot to fame as Lily Savage on British TV in the 1990s, and his legacy as a cultural icon as well as staunch LGBTQ+ advocate lives on after his sudden death on 28 March.

It would be remiss not to mention how RuPaul’s Drag Race has taken over TVs ever since the reality show first aired in 2009.

It’s no accident that legislation aiming to ban drag specifically targets drag performed in front of children

Emphasising threats to children is a well-established strategy for conveying a perceived decline of American culture, norms and values.

In the 1970s, anti-LGBTQ+ activist Anita Bryant launched her “Save Our Children” political campaign, claiming queer people were ‘recruiting children’.

Half a century later, the bigoted fears regarding advancements in LGBTQ+ rights have produced legislation restricting discussions of queerness in schools, stoked claims drag performers are ‘groomers’ and rollback access to gender-affirming healthcare for trans people.

The deployment of these well-worn, hateful narratives won’t end with drag bans.

It will continue as long as conservatives seek to battle against LGBTQ+ and trans rights in their culture war, but it won’t push queer folks back into the closet nor will it erase the integral part drag has played in art and theatre across global history.