US drag bans are nothing new – states were outlawing ‘cross-dressing’ in the 1800s

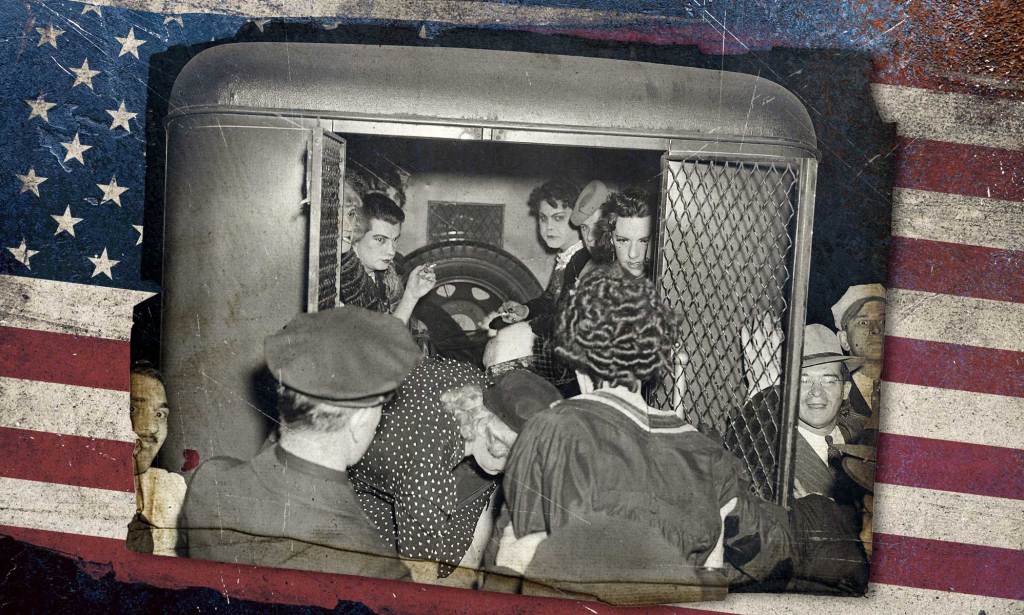

US laws have been used to target people dressing in clothes traditionally associated with another gender since the 19th century. (Getty)

Drag bans are not new. From the mid-19th century, dozens of US “masquerade laws” were used to target cross-dressing or dressing as another gender more broadly.

2023 has seen multiple US states seek to outlaw drag performances, with Tennessee becoming the first to pass legislation which was quickly blocked by a federal judge.

Despite the headlines, the Tennessee law wouldn’t technically be the first of its kind, because rules criminalising drag and gender non-conformity have been around in the US for at least a century.

From the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, dozens of areas in the US enacted legislation prohibiting appearing in public in “disguise” or “masquerade”, collectively referred to as masquerade laws.

Even when these laws didn’t explicitly crack down on gender expression, they were interpreted as applying to cross-dressing or dressing as another gender more broadly as a criminal form of concealment.

One of the oldest of these laws dates back to 1845, when New York declared it a crime to appear in public with a painted face or when wearing a disguise designed to prevent identification.

In 1848, a law in Columbus, Ohio forbade a person from appearing in public “in dress not belonging to his or her sex”, and Chicago, Illinois, passed a similar measure three years later.

They weren’t alone.

According to William Eskridge, the author of Gaylaw, “cities of every size and in every part of the country” adopted laws to enforce gender-conforming dress codes during this period.

“By the beginning of the 20th century, gender curiosity was no longer just a feminist curiosity – it was increasingly considered a sickness and public offence,” he wrote.

People who fell foul of these laws were arrested, harassed by police and committed to psychiatric facilities

Countless people were arrested under masquerade laws, including feminists, drag entertainers, cisgender people who liked to wear clothing traditionally assigned to another gender, and trans people expressing their gender.

In 1890, a San Francisco judge sent Dick/Mamie Ruble to the Stockton Insane Asylum for wearing the apparel of a different sex.

Ruble disputed the charge in court, insisting: “I’m neither a man nor a woman, I’ve got no sex at all.”

Judges and doctors viewed Ruble’s statement as evidence of mental illness, and Ruble remained in the psychiatric facility for 18 years until their death in 1908.

In 1913, a young person was arrested in the Brooklyn borough of New York for “masquerading in male attire” and was eventually sentenced to three years in a reformatory. The judge in the case said the individual was being punished because “no girl would dress in men’s clothing unless she is twisted in her moral viewpoint”.

Despite constant state violence, queer folk persisted

Masquerade laws were used for decades to imperil, harass and silence LGBTQ+ people. Anyone arrested could have their name published in the newspaper in addition to having a criminal record, potentially ruining their futures.

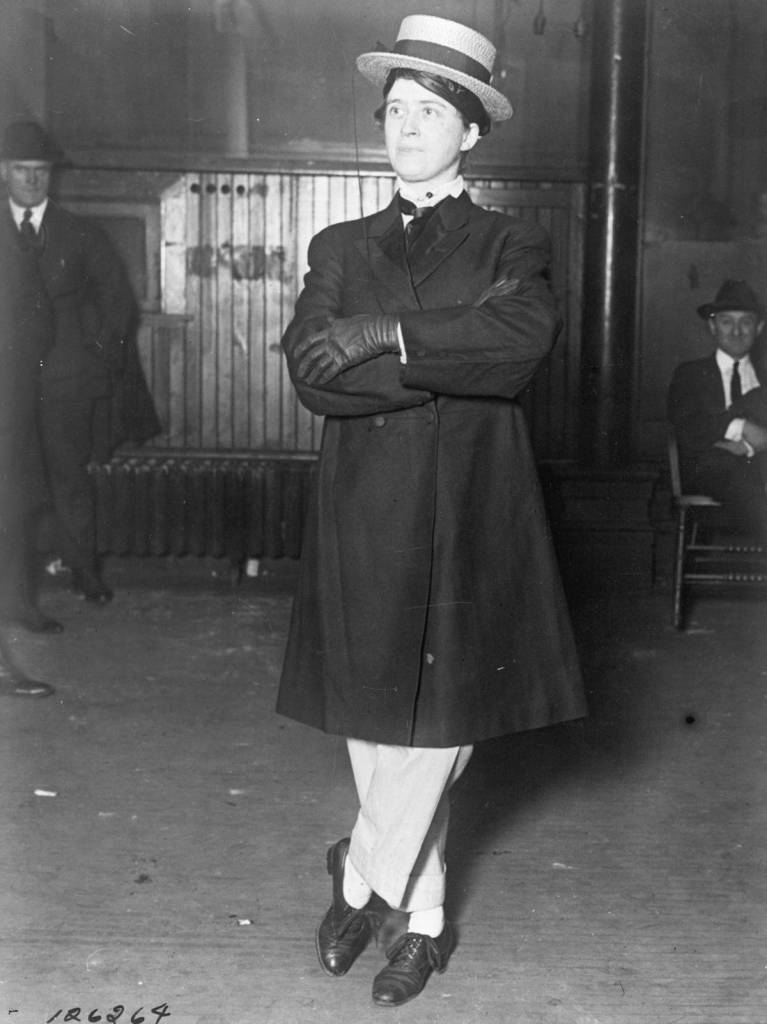

One such person was Jeanne Bonnet, who was arrested dozens of times for wearing male clothing.

But Bonnet was defiant and was quoted as telling the police: “You may send me to jail as often as you please, but you can never make me wear women’s clothing again.”

As America’s panic over LGBTQ+ people became increasingly prominent in the 20th century, and police raids on queer spaces were stepped up, arrests became more and more common.

First-hand accounts of these raids described police enforcing an informal regulation – known as the three-article rule or three-piece law – that required people to wear three items of clothing of their supposed gender. Those who violated this rule were subject to arrest and incarceration on charges of sexual deviancy.

The rule was referred to often in LGBTQ+ circles, although it didn’t appear in actual police policy.

Drag king Rusty Brown told an interviewer from the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project in 1983 that she was “arrested in New York more times than [she had] fingers and toes, for wearing pants and a shirt”. She described having to have “three pieces of female attire” to avoid being picked up by the police.

LGBTQ+ people fought back

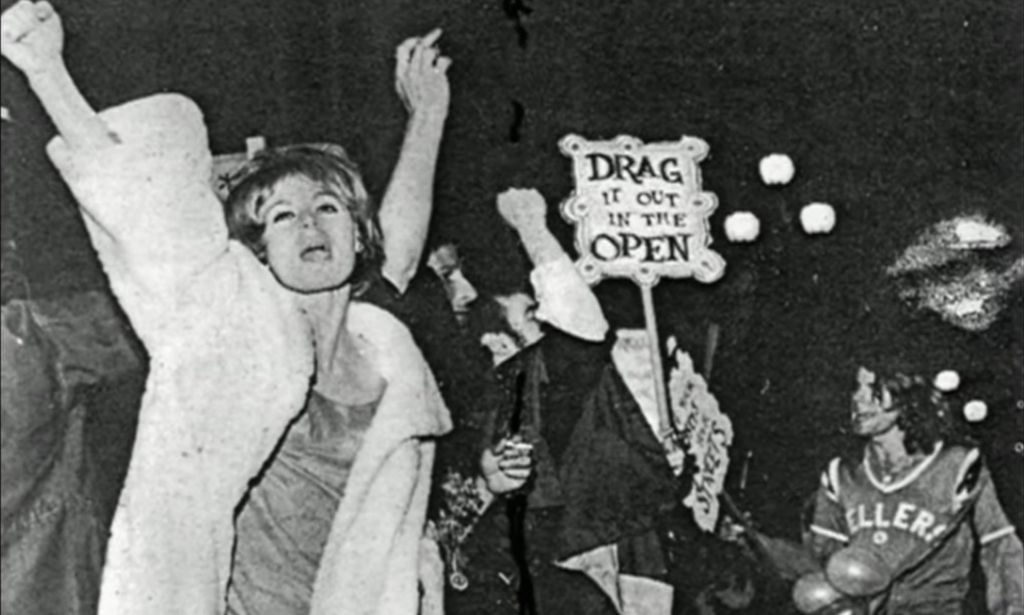

Throughout the mid-20th century, LGBTQ+ communities grew more visible, and with this visibility came increased power to enact positive change.

Activists pursued modes of collective resistance to police harassment. This included protests such as the stand at Compton’s Cafeteria in San Francisco in 1966 and the more famous Stonewall riot in New York three years later.

These were triggered in part by police harassment, abuse of LGBTQ+ people by law enforcement and arrests of queer people for breaking gendered-clothing laws.

In an interview published online by WOW Presents Plus, Stonewall veteran Martin Boyce described how he used to dress in “scare drag” as a form of protest against anti-LGBTQ+ hate in the 1950s and 1960s.

He recalled how it was an “awful era to be gay” – evading police violence and harassment was a fact of life for queer people at the time.

In a New York Times article in 2019, Boyce recalled the time leading up to the Stonewall riots and said some arrests and harassment came from the “three-article rule”, adding: “And socks didn’t count.”

The Stonewall riots directly led to the formation of new queer and trans-led organisations. They provided vital resources, support and advocacy to challenge and eventually overturn the outdated dress laws.

Attacks against the LGBTQ+ haven’t changed in more than a century

As many advocates have pointed out, the historic anti-LGBTQ+ laws and today’s drag ban bills rely on vague language to police queerness and gender non-conformity.

But the history of these attacks showed the courage of the LGBTQ+ people who doggedly fought to exist and create a better future for those who came after them.

The cries of those arrested, imprisoned and abused has given strength to the advocates now battling it out in state legislatures and on the streets of modern-day America.

How did this story make you feel?