There’s a simple reason Bud Light works with stars like Dylan Mulvaney – it’s really good for business

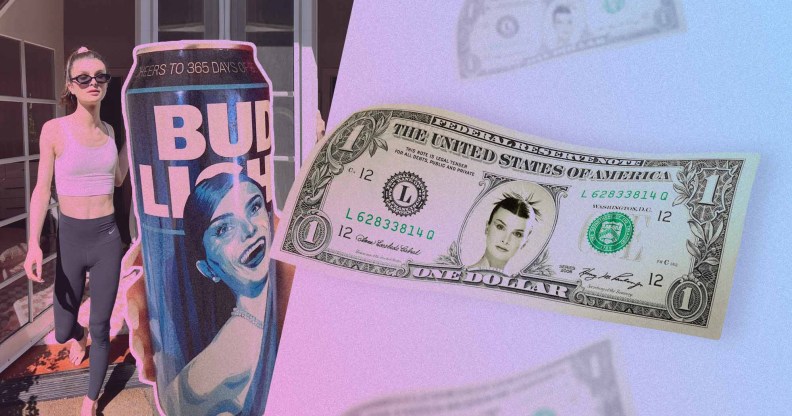

Brands such as Bud Light work with influencers like Dylan Mulvaney for more than just LGBTQ+ inclusion. (Credit: Getty / Instagram / Dylan Mulvaney)

Brands such as Bud Light work with influencers like Dylan Mulvaney for more than just LGBTQ+ inclusion. (Credit: Getty / Instagram / Dylan Mulvaney)

Try as they might to stop it, right-wingers are going to have to face the fact that LGBTQ+ representation in marketing, involving brands such as like Bud Light or Nike, isn’t going away.

The recent row on LGBTQ+ representation sparked after right-wingers issued a new call for boycotts following a Bud Light sponsorship deal with trans social media star Dylan Mulvaney.

The influencer, best known for her “Days of Girlhood” series on TikTok, shared a video on her Instagram page showing off a personalised can of beer can given to her by the beer’s parent company, Anheuser-Busch, to mark the first anniversary of publically transitioning.

Some people, angry that a beer company would give away beer, began destroying their own Bud Light cans in an attempt to convince others to boycott the brand – and for the likes, of course.

Furious right-wingers, including Kid Rock, posted clips of themselves destroying beer cans with baseball bats, machine guns and cars, in an effort to prove how “unwoke” they are.

But if any of the people posting videos were to have looked at Bud Light’s advertising history for more than a second, they would have realised that the company, and many others like it, have been LGBTQ+-positive for years.

Why? Because being pro-LGBTQ+ is popular and popularity is profitable.

Bud Light’s history is inextricably intermingled with Pride. Its website boasts the number of sponsorship drives and charitable donations it gives to queer organisations.

Not only that, but the company has been a sponsor of Canadian Pride for more than 20 years.

All this will come as terrible news for everyone who thinks it “went woke” just a few weeks ago when it teamed up with Dylan Mulvaney.

But Bud Light isn’t just working with queer organisations because it’s morally decent, but also because it’s factually proven that LGBTQ+ representation is incredibly profitable.

A study conducted by LGBTQ+ not-for-profit organisation GLAAD found that 59 per cent of Americans are more inclined to purchase a product or service if the business devotes significant resources to helping LGBTQ+ people.

Of the 2,000 consumers and workers surveyed in the study, 53 per cent not only applauded positive discussions about LGBTQ+ rights by chief executives, they outright expected it of them.

It works the same way with employment, with US employees aged between 18 and 34 being more than five times as likely to join a pro-LGBTQ+ business than one that is not.

Advertising has always been queer

Speaking to PinkNews, the joint chief executive of the UK marketing LGBTQ+ advocacy group, Outvertising, Marty Davies, said that not only is LGBTQ+ advertising profitable, but it has also been around for decades.

“You see LGBTQIA+ talent in ads of all kinds, and for all sorts of products and services, because it has been proven that adverts that include our community outperform [those] that don’t,” they said.

“They do so in ways that brands care about. Things like brand recall, affinity and purchase intent… Of course you’re going to see businesses adopt practices that help them perform commercially.”

Davies added that there’s an expectation to include LGBTQ+ people in advertising simply because it’s an authentic representation of society to do so.

“Businesses must be driving forward inclusion in their delivery of products and services. Things like changing-room policies and their work environment. Things like encouraging pronoun sharing.

“It means identifying meaningful ways where your business can support the queer charity sector.”

Trans+ Adland joint founder, Jax Kenrick, echoed that sentiment, telling PinkNews that seeing positive LGBTQ+ representation in advertising, the workplace and society as a whole, can make all the difference.

But despite the obviously profitability of representing LGBTQ+ people, it can be a doubled-edged sword.

Once a backlash ensues, businesses can be quick to drop queer advertisements because, after all, companies are there to make a profit.

“As affirming as it feels to see positive representation in your own work, I’ve also unfortunately had the experience of successfully selling trans talent to big brands who were then unable to stand by that talent when the inevitable wave of transphobic toxicity swamped them,” Kenrick said.

“It’s one thing watching prejudiced consumers lash out at brands for showing allyship to trans creators, it’s quite another working behind the scenes to push for positive queer representation… Then finding out too late that your client was ill-equipped or not well-informed enough to support our community when it counts.”