Queer intimacy coordinator explains how they make sex scenes: ‘Our bodies don’t know it’s simulated’

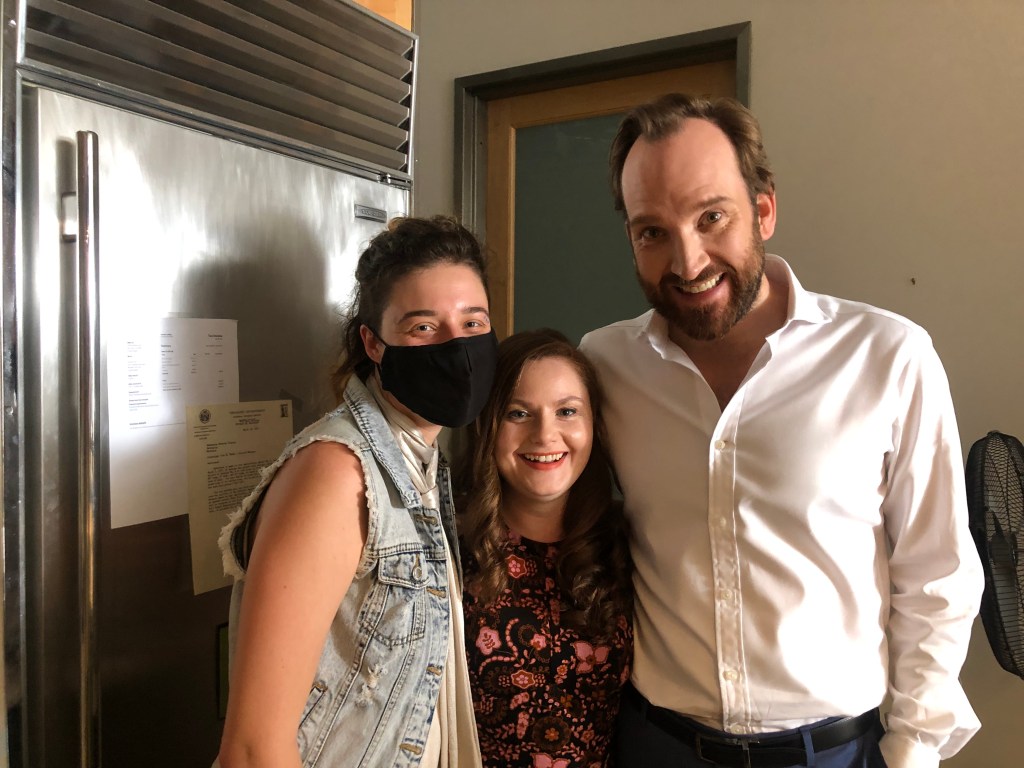

Queer intimacy coordinator Acacia DëQueer discusses why intimacy coordinators are crucial to ensure a ‘moment of desire’ doesn’t come off as a ‘moment of sexual assault’. (River Road Entertainment/Sony Pictures/HBO/PinkNews)

Queer intimacy coordinator Acacia DëQueer discusses why intimacy coordinators are crucial to ensure a 'moment of desire' doesn't come off as a 'moment of sexual assault'. (River Road Entertainment/Sony Pictures/HBO/PinkNews)

There’s been a lot of talk about intimacy coordinators lately – and not all of it has been good.

From Toni Collette to Ian McKellen, a number of established actors have made little effort to hide their disdain for intimacy coordinators, whose job is to facilitate and choreograph sex scenes while looking after actors’ wellbeing.

The role has grown in popularity in the wake of the Me Too movement, yet there has been some resistance. French film director Mia Hansen-Løve said she wouldn’t use an intimacy director unless she was “forced” to, calling them “virtue police”.

For queer intimacy coordinator Acacia DëQueer (pronouns fae/they), part of the problem is that a lot of people don’t really know what their job entails.

Yes, a big part of what they do is ensuring everyone feels safe and secure when filming an intimate scene – but it’s also about staging, character development and using sex to unveil new facets of a character’s identity.

In fact, Acacia’s job starts long before the actors get to set, fae explain. It all starts with rehearsals.

“During rehearsals we’re making sure that the actors understand exactly how they are physically approaching the scene as well as things like what their breath work is going to look like, the sounds they’re going to make, so by the time we get to set they know everything that’s going to happen.”

There’s also a practical side to what they do, from intimacy barriers to what Acacia calls “closure practices”.

“A closure practice is basically a small routine that helps people get in and out of character – it helps them leave the work behind,” Acacia explains.

“It helps reduce anxiety because they can say: ‘OK, now we’re doing this, we’re doing it for a little while and then I’m leaving that behind, I’m moving on and we’re doing something else.’ Not only does that help with anxiety, but it also helps reduce things like ‘showmances’.”

That last part is vital – actors might know on an intellectual level that the scene they’re filming is fake, but their bodies are still going through the motions.

“We say it’s a simulated sex scene – and it is – but our bodies don’t really know that.

“It produces all the chemicals that it might for a normal moment of intimacy and so it can be really hard to separate those moments for people.”

A lot of Acacia’s job revolves around harm reduction, but they also argue that it’s an art form that that should be taken seriously.

“I am an artist and when I come on set I’m not going to be quiet about the artistry part. I want to make the scene look as great as possible, as natural as possible. I want to make sure the actors don’t have a dead limp hand when they’re making out, or if I’m hearing the breathing and it sounds weird I’ll help them with that.”

They’re also not afraid to question why an intimate scene is in the script if it’s not necessary.

“If they just throw the scene in because they’re like, ‘Oh it’d be fun to have an intimacy scene, let’s do it!’ I’m gonna read it and I’m gonna be like, ‘Why is this here?’

“I don’t really want to work on something that contextually just doesn’t make sense.’ That’s not very fun as an artist for me, so I push a lot for plot driven intimacy.”

Without intimacy coordinators, sex scenes can look like sexual assault

That’s particularly important when it comes to scenes of queer intimacy. For too long, gay sex scenes were wheeled out to grab headlines rather than depict queer life in a meaningful way.

Acacia recalls the first time they saw a now famous – or infamous, depending on your perspective – sex scene in Brokeback Mountain as an example of queer sex gone wrong.

“It’s meant to be a moment of desire but it comes off as a moment of sexual assault, and I’d say that a lot of media comes off that way, even if they’re intending it not to be. I think consent is something that people don’t write into media very much at all.

“That’s on top of the fact that a lot of people don’t know how to choreograph intimacy – the way they hold their hands, the strength of the movement – it all plays into the story that’s being told.

“When people are uncomfortable, when people don’t know what they’re doing, it often comes off as a bit aggressive, stiff, uncomfortable.”

Even despite all that, most intimacy coordinators know that many in the industry still resent their presence on a set. Acacia believes a lot of the trepidation comes from a place of fear.

“There are people who think we’re the sex police and we’re trying to make things less sexy and less intimate and trying to reduce harm in that way – that’s not how we reduce harm.

“We reduce harm by providing masking techniques and barriers and choreography, by asking about people’s boundaries and making sure everyone has consent – not by saying, ‘Let’s not do this.’”

Acacia knows that some intimacy coordinators feel “discouraged” by the endless debate about their role on set, but fae try not to let it get to them.

“Everyone who is younger is so behind intimacy coordinators. I think there is a group of established professionals in the industry who feel uncomfortable with change, who don’t want to be told how to do their job, which is fine – it’s not really what we’re there to do, we’re there to support them.

“But it doesn’t bother me because I think intimacy coordinators are here to stay. Ultimately a few naysayers are just a drop in the bucket of the flood that’s coming.”