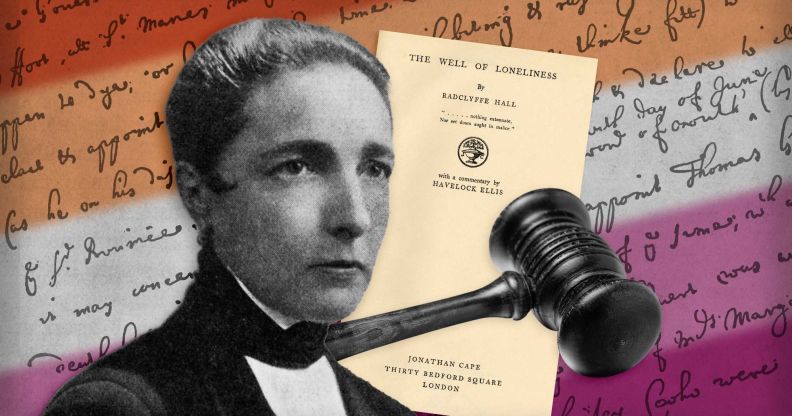

Revisiting Radclyffe Hall’s groundbreaking lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, 95 years on

The Well of Loneliness was a hugely influential lesbian novel. (Getty/PinkNews)

The Well of Loneliness was a hugely influential lesbian novel. (Getty/PinkNews)

Nearly a century after Radclyffe Hall’s groundbreaking novel The Well of Loneliness was censored in the UK, one writer explores the seminal work of lesbian fiction for the very first time.

When acclaimed author Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness was published in 1928, what followed was a literary legacy defined by lesbianism, book bans and a nation divided.

After immersing myself in queer literature for the better half of a decade – my fascination is rooted in ancient Greek poet Sappho – it’s taken me years to finally pick up this staple of lesbian literature. The novel that launched a thousand legal battles, Hall’s classic work never ventures further than describing a kiss on the lips – but after a century-long debate around LGBTQ+ representation in the media, its protagonist’s final plea to “Give us also the right to our existence!” remains as timely as ever.

With that in mind, I picked up a copy of The Well of Loneliness for the very first time to find out how the novel’s depiction of the lesbian experience holds up 95 years later.

What are the origins of The Well of Loneliness?

Born in 1880, wealth replaced parental love in Radclyffe Hall’s life. Abandoned by her father and left with an emotionally absent mother, she soon committed herself to writing. Decades on, with four successful novels under her belt and a long term-partner, Lady Troubridge, Una Vincenzo, she felt the world was ready to confront “sexual inversion”, aka queerness.

Fuelled by the desire to write lesbians into the fabric of English literature, in 1928 she told her editor Jonathan Cape: “I have put my pen at the service of some of the most persecuted and misunderstood people in the world.”

It was certainly groundbreaking at the time. Just six years earlier, in 1921, Conservative MP Lieutenant Colonel John Moore-Brabazon suggested to parliament that lesbians should face the death penalty, life imprisonment as “lunatics” or, at the very least, complete social ostracising in order to “stamp out” their existence.

While his suggestion, thankfully, never became law, it did speak to wider fears about how society had changed in the wake of the First World War. As women’s participation in the war effort shifted public attitudes towards suffrage around the world, marginalised voices increasingly became topics of conversation in public discourse. Meanwhile, across the channel, lesbian subculture was booming, with European lesbians marking their place in the elite salons of Paris pioneered by American writer Natalie Clifford Barney.

And so we come to The Well of Loneliness, which tells the story of upper-class “butch” woman Stephen Gordon. Although it’s sold as a love story between Stephen and a fellow ambulance driver, Mary Llewellyn, whom she meets during the war, the depiction of a lesbian relationship is just one facet of the novel’s seismic impact upon popular culture.

The infamous book ban

Published in 1928, The Well of Loneliness immediately sparked controversy for its frank depiction of a lesbian relationship. Despite the most explicit instance of lesbian sexuality amounting to a mere kiss on the lips, The Well of Loneliness was plunged into a fierce legal battle in November of that year.

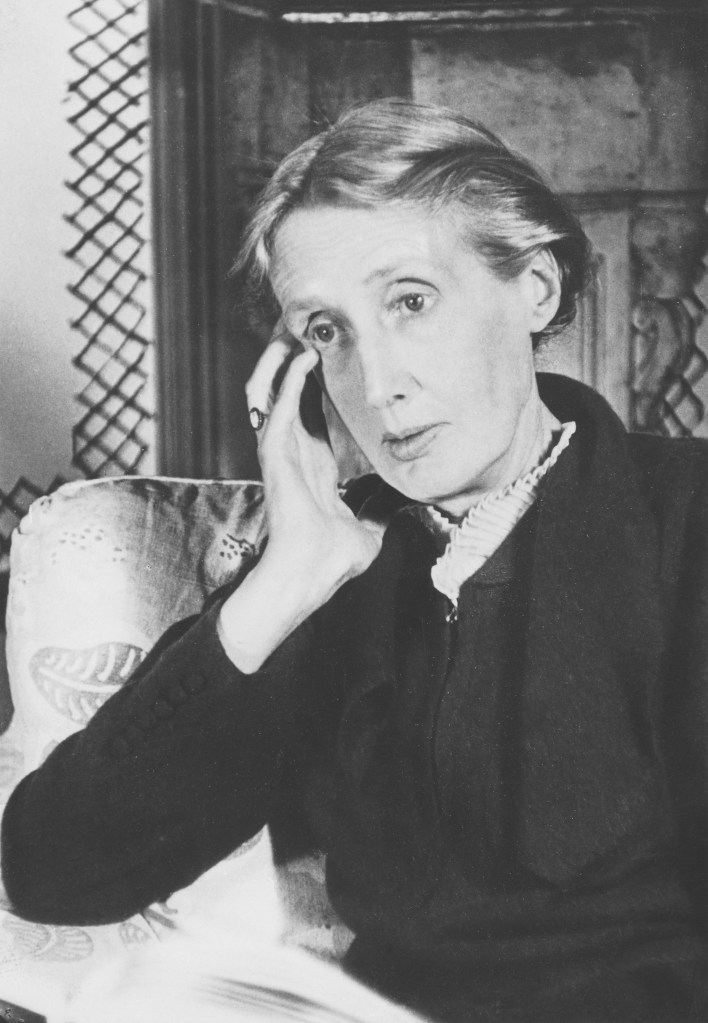

There followed huge outcry from the great literary minds of the time, including Woolf, E. M. Forster, H. G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw, who were “telephoning, interviewing and collecting signatures”.

However, The Well of Loneliness was subjected to a vicious campaign by the editor of the Sunday Express, James Douglas, who railed against the “contamination and corruption of English fiction”, eventually leading to the book being censored in the UK as a piece of “obscene libel”.

That’s not to say that Hall’s transgressive work didn’t make it into print elsewhere. The novel was available in Paris and the US, although there was a push to ban the book in the latter – ironic, given the book bans sweeping the country in the present day.

Despite support from esteemed authors, The Well of Loneliness was banned in the UK until 1949, six years after Hall’s death from cancer in 1943 at the age of 63.

How does The Well of Loneliness approach lesbianism?

In the novel, Hall gives a painstakingly detailed exploration of lesbian identity. After delving into Stephen’s psyche through childhood memories, our protagonist slowly discovers her queerness – that she loves women in the way society has conditioned her to love men – before her father’s death marks a turning point into a loss of childhood innocence.

Unlike Hall’s own doomed relationship with her own father, Stephen’s deep connection and unconditional love from Sir Phillip is surprisingly healing to read. Meanwhile, the disconnect with her mother, Anna, is one that queer children who are misunderstood by their parents will know all too well.

No analysis of Hall’s work would be complete, of course, without mentioning the inner conflict faced by the author on account on religion. Evidently Catholicism was a deep part of Hall’s identity, and one she tries to reconcile towards the ending of the book with the realisation that “inverts” are loved by God.

Hall’s regular use of the word “invert” refers to the work of Havelock Ellis and other 19th-century sexologists who popularised the concept that homosexuality was natural and normal. In an odd way, it feels like “repressed lesbian” potluck – at some point, you’ll find a passage that stops you in your tracks and puts deeply held feelings into words.

Revolving around Stephen’s tormented existence is a cast of eccentric supporting characters such as the flamboyant Jonathan Brockett, who was based on gay playwright Noel Coward, and Valerie Seymour, who takes inspiration from Natalie Clifford Barney.

It must be noted that the language in the novel is often repetitive and cumbersome; a common complaint from readers over the decades who claim that, had it not been for the controversy surrounding the trial, The Well of Loneliness would have faded into obscurity.

However, from my reading, Hall’s own lived experience is compellingly vivid, with many passages that are highly relatable for queer women who have struggled with their identity.

Praise for The Well of Loneliness

Given the media frenzy generated by the suppression and censorship of The Well of Loneliness, lesbians became a common topic of conversation, and made many people desperate to get their hands on the forbidden fruit that was banned for so-called obscenity.

In Hall’s archive at the University of Texas, in fact, newspaper clippings collected by the author in a scrapbook reveal that she received countless tributes from readers about how the book had changed their lives, with one historian estimating that she received “thousands of letters of support”.

“No one could finish your book, Miss Hall, without donning a sword and shield for ever in the cause of inverts,” one person had written. Another echoed that, saying: “It has made me want to live and to go on”.

Another read: “Some day we will wake up and demand to know ourselves as we profess to know about everything else.”

Nearly a century after Hall’s novel was first published, there are obvious parallels to be observed between the backlash against The Well of Loneliness and the growing movement to ban books covering race and LGBTQ+ topics in conservative states in the US.

Much like authors and readers who protested the censorship of The Well of Loneliness back in 1928, however, these days we’re also seeing much-loved literary figures such as Alice Oseman, Judy Blume and Juno Dawson stand up to anti-LGBTQ+ bigotry.

The complicated legacy of The Well of Loneliness

It goes without saying that The Well of Loneliness is not the be-all and end-all of lesbian representation; not least because the novel ends with Stephen, who often compares herself to Cain from the Bible, committing the ultimate act of self-sacrifice as she’s consumed by shame.

The prose, meanwhile, has attracted its fair share of criticism over the years. Alongside Virginia Woolf’s early assessment of the novel as “dull”, Canadian writer Jane Rule has also declared it “joyless” while lesbian historian Blanche Wiesen Cook attacked Hall for framing lesbianism in relation to masculinity.

Elsewhere, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit author Jeanette Winterson has been particularly damning with her criticism, branding it the “worst book ever written” and a “misery memoir”. Other critics perceive the treatment of Stephen’s love interest, Mary, as a meek woman who loves both men and women as inherently biphobic.

Hall, meanwhile, was a deeply problematic figure. Well-known for her conservative politics and aligning herself with neo-fascism in the 1930s, her work is interwoven with racism and classism which reflects her own background as an upper-class white woman.

Despite this, in recent years, new analysis of The Well of Loneliness has suggested there could be more to the book than meets the eye. Hall’s descriptions of Stephen being a man trapped in a woman’s body and her own adoption of the name John later in her life have made some wonder if Stephen may have been a trans protagonist.

Ultimately, there can be no denying the profound way in which The Well of Loneliness has shaped European literature and discourse around lesbian sexuality over the course of the 20th century. As a Pakistani Muslim woman who has grappled with her own struggles with family, self-denial and religion, many of the “joyless” passages are actually the ones that made me felt the most seen.

However, Hall’s own politics, and perhaps misguided notions about the full spectrum of lesbianism and queerness, are deeply embedded into the foundations of the novel – things we have hopefully moved beyond today.