Director Lisa Cortés on telling the true story of Little Richard’s Black, queer genius: ‘He did it first’

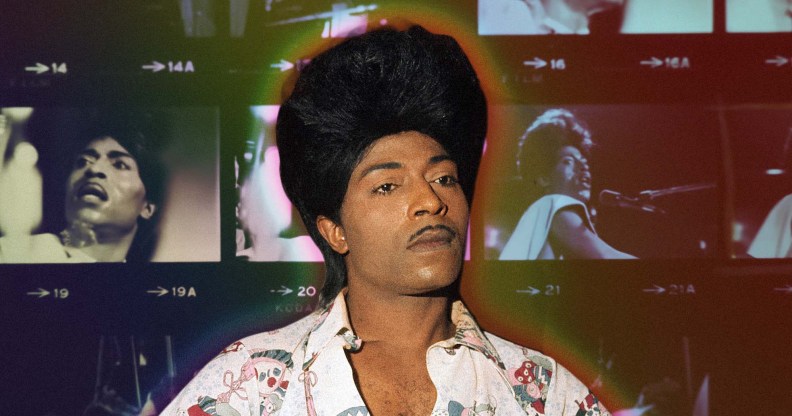

Director Lisa Cortés on the radical depiction of queer Black innovation in Little Richard: I Am Everything. (Magnolia Pictures)

As Little Richard: I Am Everything hits the big screen, director Lisa Cortés discusses the film’s radical depiction of queer Black innovation.

When Richard Wayne Penniman passed away in May 2020, weeks into an unprecedented global pandemic, musicians from all walks of life came together to pay tribute to the rock ‘n’ roll great otherwise known as Little Richard.

But as millions of fans mourned the passing of a music titan, many others were learning about his legacy for the first time.

Scrolling through tributes from the likes of Bob Dylan, Elton John, Bruce Springsteen and Mick Jagger on her social media feed, filmmaker Lisa Cortés paused as she read words of praise for the pioneering piano-rocker.

“Who is this person?” she remembers thinking. “That’s when my natural curiosity kicked in.”

Three years on, and now thoroughly immersed in the “joyous and innovative” world of Little Richard’s music, her new feature-length documentary Little Richard: I Am Everything delivers a comprehensive picture of Richard’s “rollercoaster” life – and more importantly, rightfully recognises him as a rock ‘n’ roll pioneer who influenced some of the greatest artists of the day.

Using hours of archival footage and commentary from a range of contemporary queer scholars, musicians and artists such as Mick Jagger, John Waters and Billy Porter, the documentary goes from “from cradle to grave” as it traces Little Richard’s birth in 1932 in Georgia, through to his extraordinary rise to pop culture domination and status as the the “Architect of Rock and Roll”.

Unpacking the whitewashed narrative around Little Richard’s legacy, the documentary explores the musician’s beautiful contradictions as it gets to the heart of his relationship with God, sexuality, artistry and lifelong yearning to be recognised for what he was, and remains to this day: a true revolutionary.

Known for his gender-defying costumes, high pompadour and provocative lyrics on everything from anal sex (“Tutti Frutti”) to scandalous affairs (“Long Tall Sally”), his music broke through the white American canon to capture fans from every community, and directly influenced The Beatles, Bob Dylan, James Brown and Prince, among others.

But although Little Richard presented a sparkling persona on stage, away from the spotlight, the musician was a deeply troubled man.

Despite finding chosen family within the queer community after being kicked out of his home as a teenager by his father, and indeed performing first as a drag queen named Princess LaVonne in the 1940s, Richard struggled to reconcile his identity as a gay Black man with the oppressively conservative culture of 1950s USA, an era defined by segregation and anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment.

It’s precisely these parts of Richard’s origin story, explains Cortés, that make the documentary so relevant at this moment in time.

“For the US, this film is very timely, because it’s talking about cultures and subcultures that in some places are being criminalised,” she explains, referring to hot button issues of race and LGBTQ+ identity that are being weaponised by the right wing today.

“In Tennessee, there is a movement to criminalise drag performers, and that is happening across other states. Little Richard is a byproduct of a community that, oftentimes, in the telling of history has been erased despite making so many deep, important contributions.”

As a wave of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation across the US attempts to suppress queer identity and expression, Richard’s existence as a “transgressive figure”, Cortés says, reminds us that gender fluidity and living your life in a “bold and colourful way” are simply intrinsic to American culture.

“At least going back to the 1800s, if not hundreds of years, there are documented stories of drag performers,” she explains. “It is an integral part of America and, dare I say it, world culture.”

After Richard changed the course of history with 1955 hit “Tutti Frutti“, a song explicitly celebrating gay sex, he followed in the footsteps of Blues trailblazer Billy Wright and gospel guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe to become the next pivotal voice in queer Black musical history.

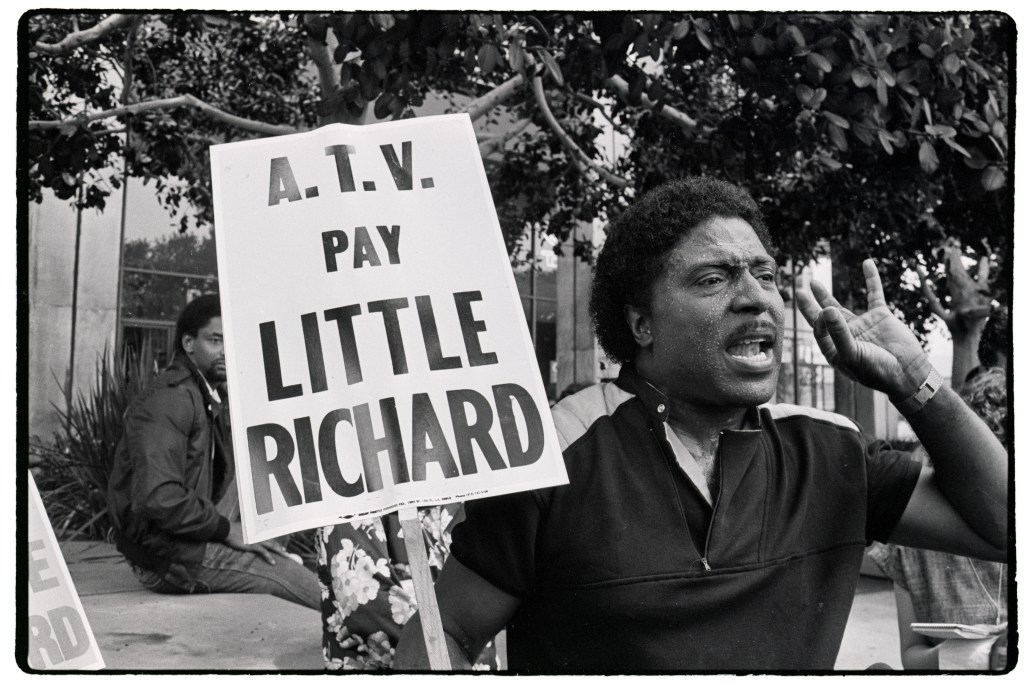

Much like those that came before him, however, his big hits were co-opted and “sanitised” for white consumption by white artists of the day such as singer Pat Boone, who surpassed Richard in the charts with his remake of “Tutti Frutti”.

Even as mainstream acts appropriated his songwriting, Richard continued to ascend with his infectious music and rebellious aesthetic, capturing the “anarchic” mood of the next generation on the cusp of the hippie movement and the Woodstock summer haze.

Cortés, who remembers watching Richard make regular talk show appearances in the ’80s and ’90s during her childhood, says his primetime appearances epitomise what a deeply misunderstood figure he was.

“It was the ‘shut up’ era, the Bronze Liberace,” she recalls. “There was no understanding that this was a man instrumental in the careers of some of the most important rock ‘n’ roll artists.

“There was no understanding of the courage it took for him to present himself as he did in 1955. There was no understanding of his legacy.”

It’s why the filmmaker, who won an Emmy as a producer for 2019 HBO documentary The Apollo, and executive produced the Oscar-winning 2009 film Precious, wanted to set the record straight – not least because no one had ever made a feature-length documentary about Little Richard.

“How many artists were inspired by his dress, his stage presence, his innovation?

“He is so much more than the guy who says ‘shut up’ on talk shows. He is so much more than the comedic foil as he appeared on these shows.”

As much a personal endeavour to right the preconceptions formed in her youth as it is to remind a new generation of Richard’s legacy, the documentary works to build a complete story of the star.

Little Richard: I Am Everything traces his childhood and early fame, time at Bible school and denouncing of his sexuality, through to his return to the music scene, subsequent rise and long-awaited recognition.

Not only does the film draw a line between Richard’s inner child – who grew up singing in church before being kicked out of his home – to his trailblazing stage persona, but it also paints a moving portrait of his unfulfilled longing to find someone to love.

While we’ll never know if he ever truly came to peace with his sexuality, Richard undoubtedly left his cultural mark.

“He was not afraid of sequins and mirrors” notes Cortés. “His fashion was like a peacock – he was unafraid to amplify what made him special through his clothing. When you look at his legacy you think ‘wow he did it first’.

“He did this in 1955 where you could get killed for being gay. He’s brave, he’s bold, he’s unique.”

Little Richard: I Am Everything is in cinemas now.

How did this story make you feel?