Senator David Norris: The man who overturned Ireland’s homosexuality ban, 30 years on

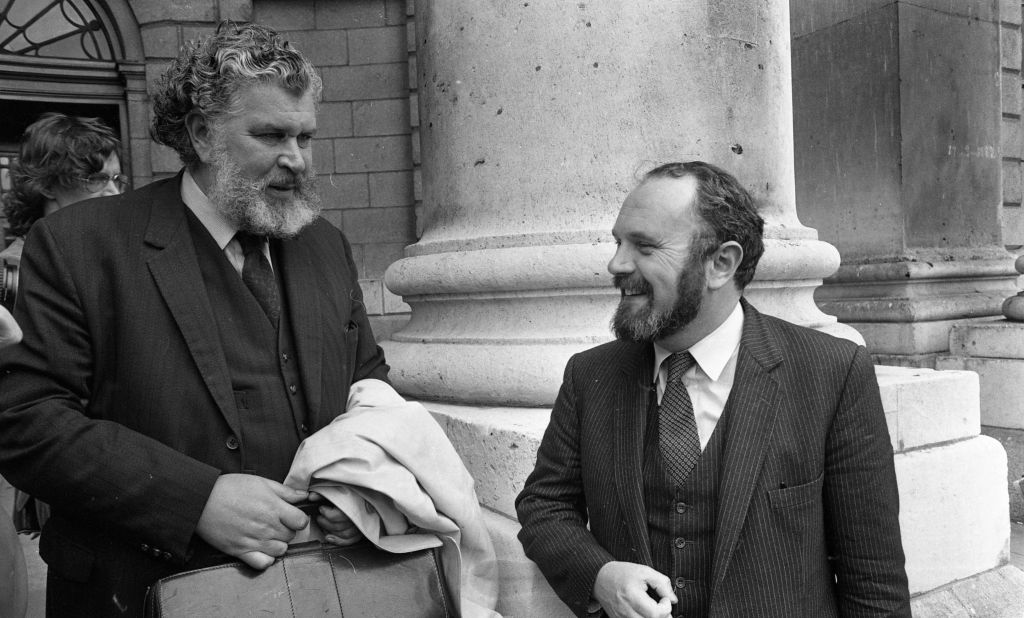

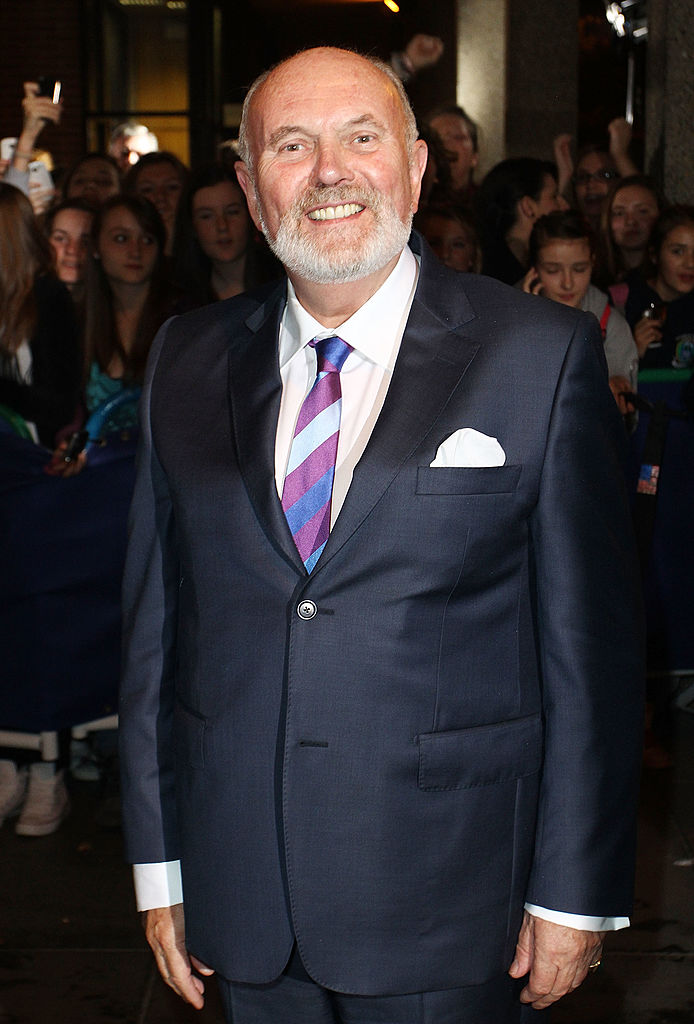

David Norris pictured in 2015 on the left and in the 1980s on the right. (Getty)

On 24 June 1993, homosexuality was finally decriminalised in the Republic of Ireland after a lengthy, tiresome battle.

It was a seismic moment for Ireland’s queer community. There was still plenty of discrimination to contend with, but for the first time people could live and love without the fear of illegality hanging over their heads.

That change would never have come about if it weren’t for David Norris. A former university lecturer who’s served as a senator since 1987, Norris famously took a case to Ireland’s High Court arguing that the law prohibiting homosexual acts infringed upon his right to privacy.

After losing his case, Norris went to the Supreme Court, where his plea for dignity was once again rejected. Finally, in 1988, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the law – which was put in place under British rule – was in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights.

That paved the way for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, although it would be five more years before the government would take any action.

Speaking to PinkNews ahead of the 30 year anniversary of decriminalisation, Norris, now 78, says gay people were “completely invisible” in Ireland when he was young.

“The Irish Times used to refer to me as ‘the Irish homosexual’ – I was practically the only one,” he laughs.

Media coverage of homosexuality was “unremittingly negative”. Profiles focused on Norris’ “hidden, shameful life”, which wasn’t how he saw himself at all.

This oppressive climate inspired Norris to launch his legal battle. While his case was lost in both the High Court and the Supreme Court, he was spurred on by what he describes as a “moral victory”.

“In the first case the judge found there was a surprisingly large number of people who were gay, that we weren’t child molesters and that we weren’t ‘mentally deficient’ and all this kind of stuff – we were just perfectly ordinary people,” Norris says.

“And then he took a swerve and said, ‘Nevertheless, because of the Christian and democratic nature of the state I have to find against the plaintiff’ – but basically his judgement was a declaration of our rights.”

In the Supreme Court, three judges ruled against him while two ruled in his favour. One of the dissenting judges said he should have won his case “automatically” because the government had, in their eyes, failed to offer any evidence as to why the law should remain in place.

Decriminalisation of homosexuality gave Irish people greater dignity

Even after the European Court ruled in his favour, the Irish government was slow to act. Norris was not surprised.

“Well, I put it to Albert Reynolds [the Irish prime minister from 1992 to 1994] who was a very decent man, very nice and I liked him, and he said it wasn’t one of his priorities,” Norris says.

Action was finally taken when Máire Geoghan-Quinn became minister for justice. Norris adds: “When it came to the actual decision to change the law it was a woman. I have to say this, I don’t think the men would have had the balls to do it, but she certainly had.”

Homosexuality was finally decriminalised on 24 June 1993 with the passage of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Bill. It didn’t change everything overnight for queer people in Ireland, but it at the very least gave people “greater dignity”, Norris says.

“It’s really pretty awful if an intrinsic part of your nature is criminalised and that I think came as a considerable relief to a large number of men.”

To this day, Norris receives letters from people all over Ireland thanking him for doing what he did. Many of them are parents who want to express their gratitude to him for making Ireland a better place for their gay sons and daughters.

“It’s lovely. Each letter is personal so there’s a story behind it of somebody’s shame and desperation and then feeling better about themselves.”

He adds: “I remember in the old days we had a kind of flying squad around the countryside, we went down to Cork and so on, and the transformation in people was astonishing – just to meet another gay person who didn’t think they were abnormal or peculiar or criminal or anything. You could see the anxiety falling away from them.”

Things have “freed up quite a lot” in Ireland since 1993, Norris says. People are more relaxed, even though violence and discrimination is never far away. Marriage equality is now a reality and the country has a vibrant queer scene.

“The other day I saw two handsome young men walking across O’Connell Bridge hand in hand, I thought that was lovely,” he says.

Norris, meanwhile, is Ireland’s longest-serving senator, and is now known as the first out gay man elected to office, rather than the only. In 2011, he ran for president.

Decades ago, Norris marched in what has gone down in history as Ireland’s first Pride march. There were just a handful of people in attendance. Nowadays, tens of thousands attend Dublin Pride.

“That just shows you the change,” he says. “It’s become a kind of carnival – people are happy and joining in. Mothers pushing babies in prams. It’s lovely.”

How did this story make you feel?