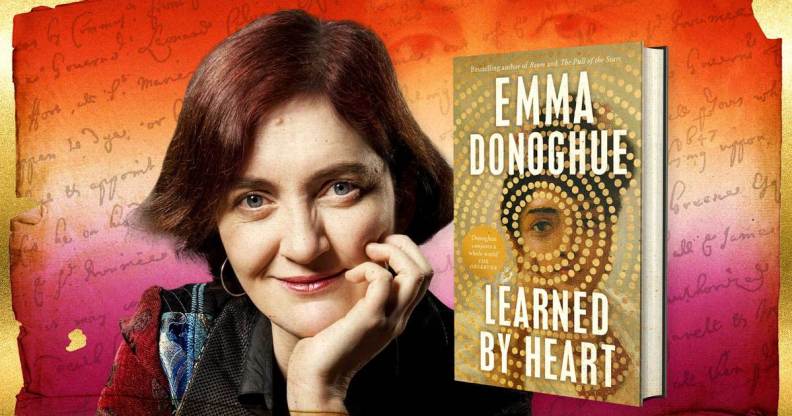

Author Emma Donoghue on her Anne Lister romance, Learned by Heart: ‘There’s no erasing us’

In a PinkNews exclusive, Emma Donighue discusses her latest lesbian romance, learned By Heart. (Portrait of Lister by Joshua Horner / Getty / Supplied)

In a PinkNews exclusive, Emma Donighue discusses her latest lesbian romance, learned By Heart. (Portrait of Lister by Joshua Horner / Getty / Supplied)

Acclaimed author and playwright Emma Donoghue has spoken to PinkNews about “buried” lesbian history, discovering Anne Lister and defiance in the face of book bans.

Booker-Prize finalist Donoghue, best known for her screen-adapted novels Room and The Wonder, started her love affair with British Regency-era diarist Lister – sometimes dubbed the first ‘butch’ modern lesbian – in a Cambridge bookstore on a rainy day in 1990.

More than 30 years after reading Helena Whitbread’s collection of Lister’s decoded entries, I Know my Own Heart: The Diaries of Anne Lister, Donoghue has brought the rarely told story of Lister’s first love, Eliza Raine, to life in a tenderly written schoolgirl romance, Learned By Heart.

Lister’s early 19th-century life, spent in Shibden Hall, in Halifax, found mainstream recognition in 2019 with hit BBC series Gentleman Jack which chronicled Lister’s final relationship, with Ann Walker.

The rich tapestry of Lister’s life – documented in her five-million-word coded diaries, peppered with dazzling stories of Yorkshire’s queer underbelly – naturally drew Donoghue in.

“It’s hard not to describe myself as if I’m one of Anne’s ex-girlfriends,” Donoghue jokes while talking to PinkNews. “But we know from her diaries that she hooked herself in the heart of so many women. Almost nobody could resist her.

“Her voice is so honest and frank and flavourful, she records everything. It’s like a glimpse into this covert world of discreet relationships between women that the patriarchy didn’t notice, because ‘Oh, it’s just girls hanging around together’.

“The only difference is that Anne wrote it all down and miraculously nobody burned those diaries.”

Although Lister should rank in history alongside LGBTQ+ influences such as Greek poet Sappho and American poet Emily Dickinson, her status as a “pop culture icon” has only been earned in recent decades.

“In the early days, I felt like one of a very tiny club of those who were interested in these things,” Donoghue admits. “It’s a huge community now, so it certainly doesn’t feel like a little private club any more.”

A crucial element of catapulting Lister to widespread acclaim was the tireless work of codebreakers who unravelled the cipher she used to disguise her romantic affairs with other women.

Donoghue herself recruited 14 women to decode the correspondence between Lister and Raine, from when hey first met at Manor School for Young Ladies, a boarding school in York, in 1805, to their final correspondence in 1814 when Eliza admitted herself to an asylum.

“I wanted it to be about the school and the asylum,” Donoghue says about the decision to split the book’s timeline across a decade. “I wanted to make an agony out of the chasm between their happy schoolgirl affair and Eliza’s tragic future, because the book is really all about nostalgia.

“It’s for everyone who has ever looked back on their first love and been like: ‘Oh, how come it doesn’t feel like that any more?'”

And it was the small details hidden within the letters that elevated the story in a way Donoghue could never have imagined. “From one particular letter, someone on Twitter found me, [and] they had a lesbian teacher,” Donoghue says.

“One of the teachers moved north with her female partner. I probably wouldn’t have invented a lesbian teacher because I would have thought, ‘No, that’s too convenient’. But they had one, so there we go.”

Despite Lister’s star quality, it felt inevitable that Raine would end up “grabbing the mic” when Donoghue finally put pen to paper in 2014.

“Why have people not been writing about Eliza over the past 30 years? This first love affair at school, set each of them on a course that changed their lives,” the novelist says.

As a mixed-race woman, Raine was both an heiress and an illegitimate orphan whose love-filled early years ended with her doomed to spend the final decades of her life in a mental institution. Her complex existence enthralled Donoghue and drove the author to write fictional letters to Lister from Raine’s perspective.

“[Eliza’s real letters] showed the volatility of her moods, an implicit pre-history to her big breakdown that she had in her twenties – this aching vulnerability, this clinging to nostalgic love for Anne and [the] memory of their happy days together.

“She loved music, she loved poetry, and she loved Anne above all things. She was imprinted with this burning love story in her teens and just couldn’t forget it. She couldn’t move on. It’s heart-breaking,” Donoghue adds.

But Learned by Heart goes beyond simply telling a sapphic love story. The author understands that publishing a coming-of-age queer romance is more necessary than ever amid queer book bans, anti-LGBTQ+ legislation and rising homophobia.

“Maybe 10 years ago, I might have thought there’s no need for a story about two girls falling in love,” she reflects. “But after the anti-queer backlash I’m seeing in the States now, it’s become urgent again to say that we’ve always been here, there’s no erasing us.”

Donoghue, who has won awards for her lesbian fiction Hood (1995) and Slammerkin (2000), goes on to say: “To me, it’s always seemed like a slow progress until maybe a year or two ago and it’s alarming. I know one publisher in the States who publishes very diverse books for young readers and their sales are plummeting because booksellers and librarians are afraid to put in orders.

“If you write about underrepresented lives, there’s a knee jerk ‘anti-woke’ reaction, the idea that you’re just telling these stories to be woke when in fact you’re wanting to tell the truth.

“I’ve been really shaken by what’s happened recently.

“I didn’t choose to write a novel about 14-year-old lesbians specifically to tackle this moral panic about queer youth. I planned the novel a long time ago, and they just happen to be 14, but it does feel particularly timely.

“It’s a good moment to speak loud and clear in a mainstream-published book about queer teenagers and the timeless aspects of their love.”

It’s a full-circle moment given that books saved Donoghue’s life when she was growing up as a lesbian in Catholic Ireland in the 80s, which, she says, felt rather like the 19th century.

“I had this feeling that I was the only one,” she says. “So, I know that when I came across things like the poetry of Emily Dickinson and her love poems to her sister in law, it was hugely supportive for me to feel not only that others had felt what I felt, but [also] that they’d felt it hundreds of years ago.

“We’re not some passing phase. Having access to your own history is like a crucial vitamin in the diet.”

Learned by Heart by Emma Donoghue is available to buy now.