What happened in Scotland’s gender recognition reform law court battle with UK government

Holyrood and Westminster are in court over Scotland’s gender law reform bill

A court battle between the Scottish and UK governments over a gender reform bill has concluded, with a ruling not expected for “some time”.

This week, Holyrood locked horns with Westminster in a fight to overturn secretary of state for Scotland, Alister Jack’s, veto of the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill (GRR), which was blocked from gaining royal assent in January.

The bill, which would make it easier for trans people to change gender, has become a constitutional battleground with trans rights dragged into a skirmish about devolved powers and Scottish independence.

At the Court of Session in Edinburgh, the case was heard by judge Lady Haldane, who said on Wednesday (20 September) – after the judicial review concluded a day earlier than expected – that she will take “some time” to reach her decision on the matter.

The judge retired to consider the evidence and write her opinion following what she described as a “unique, very interesting and challenging case”.

What is Scotland’s gender law reform bill and why was it blocked?

Scotland’s GRR bill was passed by 86 votes to 39 votes in December, following years of consultation by the Scottish government.

The bill was introduced after lengthy campaigning by the trans community for changes to be made to the 2004 Gender Recognition Act (GRA), and would seek to simplify how trans people can change their gender on legal documents in Scotland.

When the GRA was signed into law, it was a huge step forward for trans people but in the years since there has been criticism of the legislation, particularly about how people obtain a gender recognition certificate (GRC). The process to legally change gender has been described as difficult, inaccessible and highly medicalised.

In the UK at the moment, trans men and women must apply to the Gender Recognition Panel and present reports as well as a diagnosis of gender dysphoria – a process that can take years, given the long waiting times at NHS clinics.

Scotland’s reform law sought to remedy this and update processes and systems to make life a bit easier for Scottish transgender people.

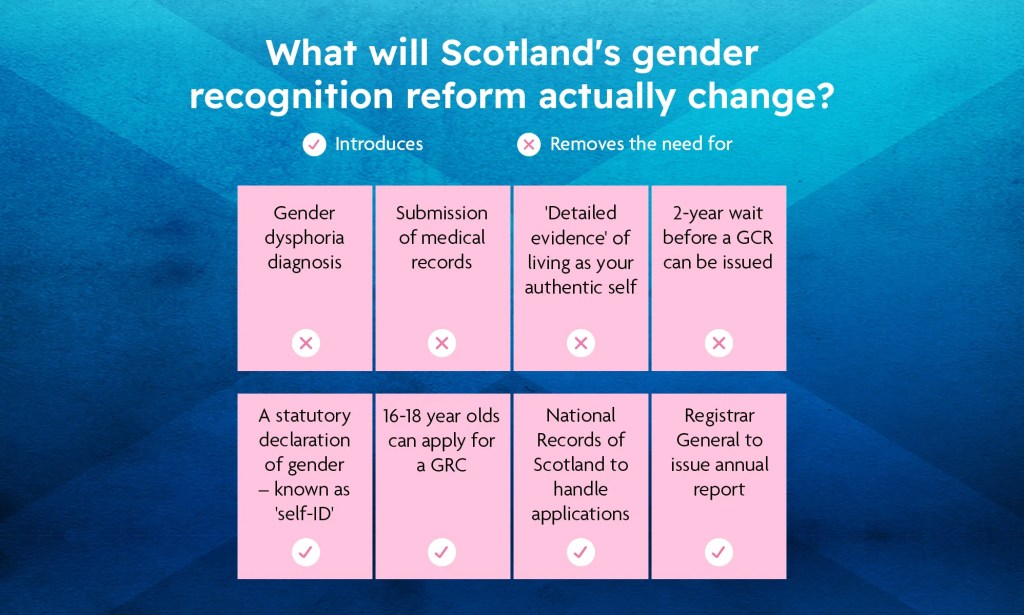

The law would see applications handled by the country’s registrar general, rather than the UK’s Gender Recognition Panel, and open up the legal transition process to teens aged 16 and 17 for the first time.

It would remove the highly medicalised process, by taking away the requirement to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, and implement a system of self-ID.

Additionally, the period in which applicants need to have lived in their acquired gender would be cut to three months – six months for those aged 16 and 17. There would also be a new requirement of a “waiting period” of three months after applying, during which an individual must reconfirm their wish to receive the GRC.

Following the bill’s passage last year, the UK government announced it would invoke Section 35 of the 1998 Scotland Act to block the legislation.

Section 35 gives Westminster the power to intervene on bills “which the secretary of state has reasonable grounds to believe would be incompatible with any international obligations or the interest of defence or national security”.

Westminster’s use of this legal device was a first-of-its-kind move since devolution, making it an unprecedented political decision which reignited debates around devolved powers and Scottish independence.

In an address to parliament the following day, Jack cited “single-sex” spaces and “equal pay” protections as reasons for preventing the proposed law gaining royal assent. The UK government had concerns the legislation would have a “serious adverse impact, among other things, on the operation of the 2010 Equality Act,” he added.

“Those adverse effects include impacts on the operation of single-sex clubs, associations, schools and protections such as equal pay. The bill also risks creating significant complications from having two different gender recognition regimes in the UK, and allowing more fraudulent or bad faith applications.”

The move was branded by then first minister Nicola Sturgeon as a “full-frontal attack on democracy” and an “attack on our democratically elected Scottish parliament and its ability to make its own decision on devolved matters”.

What was said in court?

The case got underway on Tuesday (19 September) with the Scottish government presenting its argument first, followed by Westminster’s lawyers the next day.

The legislation itself was not discussed, with the case instead focusing on whether or not the Jack had the legal right to veto the bill.

Whoever loses the case, when Lady Haldane issues her ruling, will have the right to appeal the outcome at The Court of Session Inner House. Whoever loses that appeal will have the option to take the case to the Supreme Court in London.

This means, regardless of the result, the political and legal battle could go on for months, or even years.

On the first day, lord advocate Dorothy Bain – the Scottish government’s chief law officer – said the court has a “constitutional duty” to review the order and accused the Scotland secretary of “closing his eyes” to one side of the gender reforms debate.

As reported by The Herald, Bain said Scottish ministers regard the use of Section 35 as unlawful, and the reasons given by Jack to justify its use were, they believe, “insufficient in law”.

If Westminster is successful in using Section 35 to block the GRR, the Scotland secretary could, in the future, “veto practically any act of the Scottish parliament having an impact on reserved matters because he disagreed with it on policy grounds”, she added.

“That would be tantamount to the Scottish parliament being able to legislate only insofar as the UK executive consented.”

Bain went on to say that a Section 35 order should be “tightly controlled” and only used as a “last resort.” She also questioned the UK government’s response – they issued the order four weeks after the bill had been passed.

Jack’s reasons for blocking the bill – notably that it would have negative impacts on the Equality Act – were “either unfounded, too speculative or hypothetical, or insufficiently cogent and material to justify the exceptional step of making the order”, she argued.

However, at the end of the first day of the hearing, David Johnston, the UK government’s lawyer, said about Section 35: “There’s nothing sinister about this power. This is part of the scheme.

“It cannot be emphasised too strongly, that it’s part of the scheme of the [Scotland] Act. It’s part of the machinery by which government in the United Kingdom operates,” The Herald reported him as saying.

He went on to explain that Section 35 exists to enable the Scottish government “to work within its competence” while, on the other hand, it “empowers the secretary of state, on limited grounds, to intervene when there’s a concern about adverse effect on the operation of the law applying to reserve matters”.

The order was issued to “protect the interests of the United Kingdom if [Jack] identifies adverse effects on the operation of law, as it applies to reserved matters”, not as a means to scrutinise policy, he claimed.

The idea that Section 35 was involved over a policy disagreement between Holyrood and Westminster was a “red herring”, he told the second day of the hearing.

“Whether or not it is a disagreement is simply irrelevant,” he argued.

How did this story make you feel?