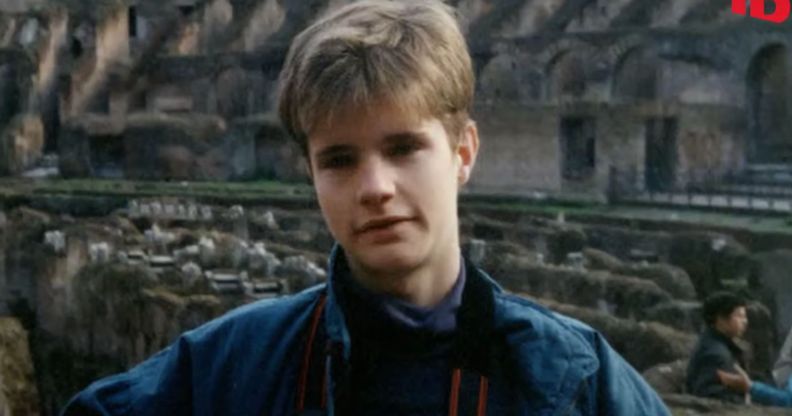

Matthew Shepard remembered by friends 25 years after brutal homophobic killing shocked the world

Matthew Shepard’s parents are ‘tired of being angry’ over LGBTQ+ rights. (Investigation Discovery)

Matthew Shepard's parents are 'tired of being angry' over LGBTQ+ rights. (Investigation Discovery)

“He was a total nerd,” says Romaine Patterson, the 45-year-old LGBTQ+ rights activist and close friend of Matthew Shepard, whose brutal murder 25 years ago shocked the US.

Shepard – a 21-year-old, gay student from Wyoming – loved theatre, but was also deeply interested in political issues and current affairs, and had learnt several languages, including German and Italian.

He was also very much a people person. “He was always looking to meet new and interesting people,” Patterson remembers.

She met Matthew via his therapist. He had asked to be put in touch with other LGBTQ+ students on campus at Casper College in Wyoming, where he was studying at the time. When Patterson was at work, in a local coffee shop, Matthew would come by and spend the day chatting with her, people-watching through the window and striking up conversations with strangers.

“It was one of the unique things about his personality. He always approached a new person as a potential new friend,” Patterson says.

She believes that could explain why Matthew ended up in the company of Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, the two men who would, on the night of Tuesday 6 October 1998, go on to brutally beat and torture him before leaving him for dead, tied to a fence near Laramie in rural Wyoming.

Matthew died six days later.

To avoid the possibility of receiving the death penalty, Henderson pleaded guilty to murder and kidnapping and was sentenced to two consecutive life terms in prison. McKinney’s case went to trial a year after Matthew’s death. He was convicted of felony murder, aggravated robbery and kidnapping. He is also serving a double life sentence.

Twenty-five years on, Matthew’s murder remains one of the most horrific – and notorious – homophobic hate crimes in US history.

His violent death also marked a turning point, as the nation finally began to reckon with its deep-rooted homophobia.

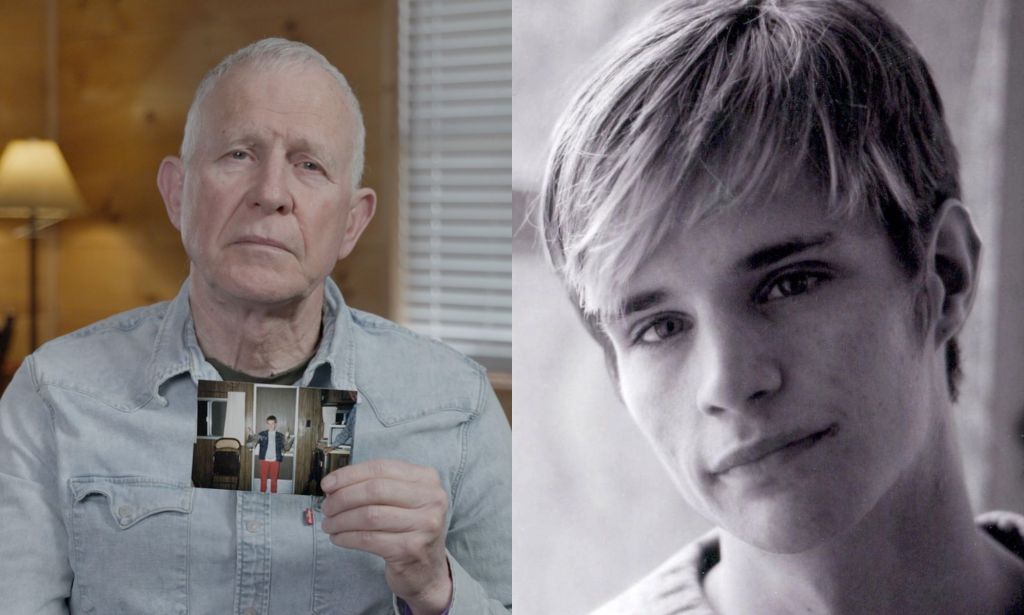

The story of Shepard’s bright life and tragic death has been told through a variety of books, films and documentaries over the last two and half decades. In the latest, The Matthew Shepard Story: An American Hate Crime, Patterson and another friend, Jim Osborn, along with celebrities Rosie O’Donnell, Adam Lambert and Book of Mormon star Andrew Rannells, reflect on who he was, and why his story still matters today.

“Matt had this infectious energy, just talking to him for a couple of minutes could make your day better,” recalls Osborn. He only met Matthew, at the University of Wyoming, two months before the tragedy, but the pair quickly became close.

They met through the university’s LGBTQ+ student association (Osborn was the chairman, and Matthew had sought out the group before the academic year had even begun). On the night he was attacked, the group had convened, then gone out for pie and coffee.

Around 24 hours later, Osborn’s life changed for ever. “Being here in Laramie after the news broke was surreal because it was like somebody had flipped a switch,” he says.

It was an overwhelming flurry of emotions: as US media flocked to the small city to cover the abhorrent assault, the University of Wyoming was hosting its annual homecoming event, welcoming students and alumni back on to campus. The usually joyous occasion was “sombre and sullen”, as the Laramie community confronted a display of hatred and violence it had never experienced before.

Despite deep despair, the community – and eventually the rest of the US – found hope and solidarity. Hope that Matthew would pull through, and solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community in the face of such extreme bigotry.

Until then, Osborn’s home town had swept LGBTQ+ issues under the carpet. “Overnight, we had businesses and individuals hanging bed sheets and signs out of their apartment windows, [reading]: ‘Hate is not a Laramie value’. It was very gratifying to see that.”

After Matthew died, there was an outpouring of grief. Candlelit vigils were held across the US, while Patterson, who had been based in Denver, stood on the steps of the State Capitol and passionately addressed mourners. Something changed.

“That sadness turned into: ‘I can’t believe something like this happened. How did we create a situation where something like this happened?” she recalls. The fury spilled out of the LGBTQ+ community, too: straight people were beginning to question how such hatred could exist.

“It started to bubble into anger and action. Once he died, and I saw that collective, overwhelming emotion that the world was feeling for Matthew, I thought: ‘Oh, there is something to this. This might actually be a real moment of change’.”

In the weeks, months and years which have followed, Patterson and Osborn have dedicated their lives to LGBTQ+ advocacy.

Osborn is a regular speaker at colleges and universities across the country, raising awareness of LGBTQ+ issues and speaking out about hate crime and violence.

Patterson wrote a book about Matthew, has hosted LGBTQ+ radio show Derek and Romaine for two decades, and worked as a media manager for GLAAD.

“To say that our lives would never be the same is such an understatement,” she says. She and Osborn felt they had to honour Matthew, but also use the national spotlight to speak to the wider issues facing LGBTQ+ people. “Something good had to come from something so horrible.”

And it did. Two months after their son was murdered, Matthew’s parents Judy and Dennis founded the Matthew Shepard Foundation, which remains active today, fighting for equal rights and empowering people to tackle hatred.

After Matthew’s friends and family fought a tireless, decade-long battle, president Barack Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act into law in October 2009.

The legislation finally permitted federal-level prosecutions for crimes based on sexual orientation, gender, gender identity and disability. (Wyoming is yet to pass such a law at state level. “Don’t even get me started on how mad that makes me,” Patterson says).

This, said Dennis Shepard in March, plus the fact that LGBTQ+ Americans feel more able to walk down the street hand-in-hand, is Matthew’s lasting legacy.

For Patterson and Osborn, that legacy can be seen most prominently in The Laramie Project.

The play, originally written by Moisés Kaufman in 2000, has been produced in schools, colleges and communities thousands of times in the past 23 years. It tells the story of how events unfolded after Matthew’s death, and how the community came together to unite against hatred.

“It is such an educational tool to talk about our thoughts and our feelings – the good, the bad, and everything in between,” Patterson says. “It makes people stop and look at their own communities, and it makes them look at their own bias. It changes people.

“I believe that that is truly the lasting legacy of Matthew Shepard.”

Although the world has progressed in leaps and bounds since Matthew’s murder, both Patterson and Osborn sound exasperated, as politicians and the public across the US appear to be taking renewed aim at the LGBTQ+ community, with trans people particularly bearing the brunt.

As Dennis Shepard warned earlier this year: history could repeat itself.

“The rate of crimes against transgender women, especially women of colour – it’s astronomical,” Patterson sighs. “The fact that we are not talking about it every single day makes me crazy, because their lives matter. Their lives are important.”

Osborn agrees. “The frustration of watching the news and seeing our elected officials, who are supposed to be looking out for the people they serve, and talking about us as though we are less than human, talking about us as though we are predators… it feels like sometimes some things haven’t changed.

“It’s incredibly frustrating to see the pendulum swing back, in some ways further than it was in 1998,” he says.

Although Matthew’s story is for ever intertwined with the horrific homophobic hate that took his life and the violence that LGBTQ+ people still face today, Patterson and Osborn try to remember him as the person he was before that terrible day in October 1998.

“Matthew was very well put together. He took a lot of pride in his appearance,” Patterson recalls.

“He always wore khaki slacks and a blue button-down shirt. He had more blue button-down shirts than any human being I’ve ever met. He had this adorable little gay face. I don’t know how else to say it, he had a cute gay face.”

Osborn remembers Matthew best for the nights they spent working at the university’s LGBT association, planning for events such as LGBTQ+ awareness week. When the work was through, they’d carry on chatting and laughing in local restaurants for hours afterwards.

“We would invade and push the tables together, and we would have been a nightmare for the servers if we weren’t also well behaved and tipped well,” he reflects.

“That’s the way that I always try to remember Matt, hanging out and laughing with the rest of the members of the group, and just being a friend.”

The Matthew Shepard Story: An American Hate Crime premiered on ID and is streaming now on Max in the US.