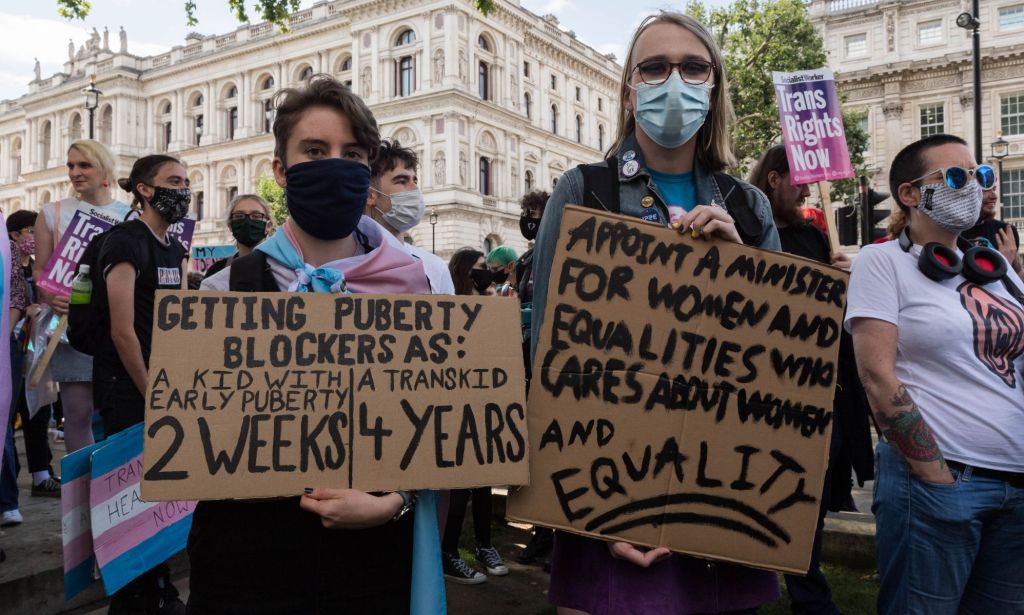

‘I started questioning my gender at 14 – NHS England puberty blockers decision fails trans teens’

The British Medical Association has called for a ‘pause’ in implementing the recommendations of the Cass Review.(Getty) (Getty)

I first started questioning my gender when I was 14. For many young trans people this happens sooner. For others, the realisation comes later in life.

It’s a scary time to be a gender-questioning youngster in the UK. The all-too-common adolescent fear of knowing your place in the world is exacerbated by feelings that you know are incredibly real, but, whether intentionally or not, are treated as a sickness by those around you.

I can’t imagine what living as a young trans person today must be like, now that the true sickness of transphobia has seeped into the foundation of the UK like poison in the water. What I do know is that my feelings never left me and, statistically, the same is true for today’s transgender youth.

Whatever justification NHS England has afforded to make the ill-thought-out decision to stop prescribing puberty blockers to all but a few on its ever-growing waiting list, the experts know the current state of trans healthcare in the UK is not good enough.

The NHS England review, published on 12 March, argues that there is “not enough evidence” to support the use of puberty-suppressing hormones by under-18s other than through clinical trials – the punctuation mark to the years-long snuffing out of an already underfunded and disregarded health service.

The news, quite rightly, caused concern among various LGBTQ+ and medical advocacy groups, which branded the ludicrous position as just that. Stonewall, Mermaids, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and others, have demanded NHS England reverse a decision that essentially cuts off new referrals with little reasoning.

While it is an undoubtedly shocking development, it is by no means surprising to those who have been paying attention to NHS England’s – at-best – inconsiderate and, at worst, politically compromised, decision-making over the past few years.

Last June, following an interim report by Dr Hilary Cass, as part of a full review, NHS England justified a decision to instigate puberty blocker restrictions only in “exceptional circumstances”.

The interim report simply says that the model of care the NHS was using at the time was outdated – which it was – but this has been used to justify trans youth clinic closures, imposing further restrictions on healthcare for trans-under-18s, and has now seemingly led to an end to new prescriptions of puberty blockers at gender clinics.

The reality is that waiting times for under-18s ranged up to 36 months before the Tavistock closure and eventual restructure, which has been delayed several times, making the wait even longer for early stages of care.

Fewer than 100 young people in England were prescribed puberty blockers by the NHS last year and, according to Mermaids, barely any first appointments were made at the Gender Identity Development Service in 2023, despite a waiting list of at least 5,000 people.

All of this has culminated in what has essentially become a disastrous stagnation, which the NHS would rather turn its back on than address. Try as it might, no amount of covering its ears and closing of eyes is going to magically make the dysphoria of these young people go away.

Naysayers who have never met a single trans person in their life, and fuelled by shrill media fear-mongering, like to pretend that dysphoria is somehow something that can only be understood the moment you hit 18. I can tell you first-hand that that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Dysphoria is a silent killer that, if left unaddressed, can gnaw at you and turn you inside out. My teenage years, like many transgender people before me – and for those to come – were plagued with anxiety and depression that did not go away with cognitive behavioural therapy or anti-depressants, but could have with the help of vital treatment that I was unable to access.

Those teenage years can have a profound effect on your adulthood, and denying trans youth the right to a comfortable childhood is just not good enough.

Study upon study show that, under the right system, puberty blockers can be life-changing and life-saving. In Australia, a body of research found that gender-affirming care halves suicidality among trans people and that, of those people undergoing puberty blocker treatment, less than one per cent detransition.

The Cass report itself even advocated for medical professionals to help trans youth “at the earliest feasible point in their journey” because studies have proved that it can save lives.

NHS England’s own website describes puberty blockers as “physically reversible” and, while it notes that the psychological effects need to be studied further, research shows that, in the right hands, they can be a life-changing intervention.

Those who spout comments about regret and puberty blockers being supposedly being handed out like sweets, are misinformed: regret rates in the UK make up about 0.47 per cent of patients in the gender identity clinic alone, while recent research found that, out of 548 people referred to Western Australia’s only youth gender service, only two detransitioned.

Perhaps NHS England is aware of these statistics, perhaps not. What is abundantly clear is that transgender youth themselves are not being heard or treated with the respect they deserve.

How did this story make you feel?