Meet Audre Lorde: The blind lesbian civil rights activist who revolutionised Black education

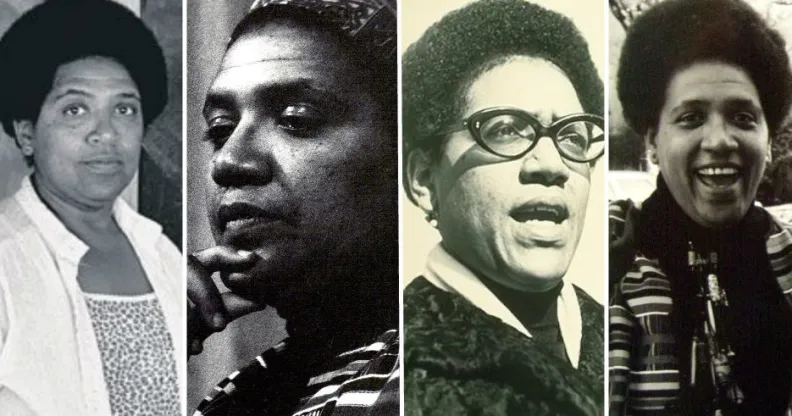

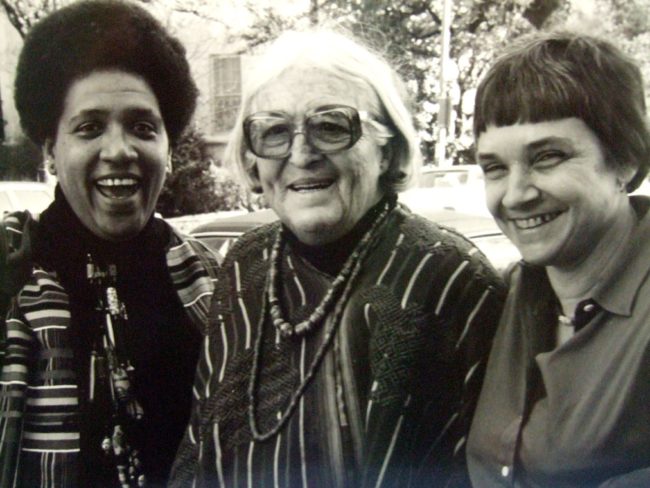

We owe a great deal to Audre Lorde (Wikimedia Commons/Getty)

African-American lesbian feminist writer, poet and civil rights activist Audre Lorde was 58 when she died in November 1992. However, her legacy will live on forever.

To mark Black History Month 2024, which takes place in October in the UK, we decided to take a closer look at her many achievements.

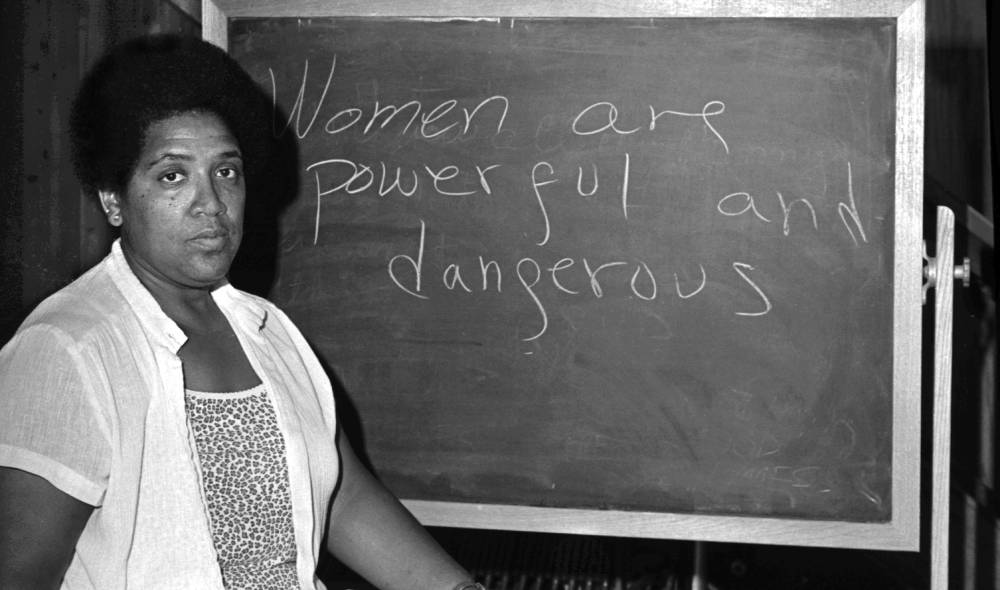

Lorde was a tireless and passionate advocate for equal rights, and dedicated her life and her work to fighting and addressing the injustices of racism, sexism and homophobia.

She famously said: “Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference – those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older – know that survival is not an academic skill.”

She went on to set up the first American publisher for women of colour amongst her other inspirational and ground-breaking achievements.

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde (she later dropped the Y in Audrey) in 1934 in Harlem, New York, Lorde’s parents were from Barbados and Carriacou.

Despite being near-sighted and classed as legally blind, Lorde taught herself to read when she was just four years old, also memorising poetry from a young age.

Audre Lorde’s early life

Audre Lorde attended Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students. While studying there, she published her first poem in Seventeen magazine – after it was rejected by her school’s literary journal for being inappropriate.

She later attended the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 1954, Hunter College, New York in 1959, and Columbia University in 1961, where she got a master’s degree in library science. She worked as a librarian in New York, where she also actively participated in the gay culture of Greenwich Village.

Innovating university life

In 1968, Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, which inspired her book of poems Cables to Rage.

She also taught at Lehman College and Hunter College, and was a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice where she fought for the creation of a Black studies department.

“As a Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, poet, mother of two including one boy and member of an interracial couple, I usually find myself part of some group in which the majority defines me as deviant, difficult, inferior or just plain “wrong.”

From my membership in all of these groups I have learned that oppression and the intolerance of difference come in all shapes and sizes and colors and sexualities; and that among those of us who share the goals of liberation and a workable future for our children, there can be no hierarchies of oppression” – Audre Lorde

She became an associate of the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP) in 1977, and in 1981, Lorde was among the founders of the Women’s Coalition of St Croix, an organisation assisting women who had survived sexual abuse and intimate partner violence.

Later in the ’80s, she helped establish Sisterhood in Support of Sisters (SISA) in South Africa, helping Black women who were affected by apartheid and other injustice.

Lorde was also a visiting professor for many years at the Free University of Berlin, where she coined the term ‘Afro-German,’ which brought about the Black movement in Germany.

Dagmar Schultz made an award-winning documentary about Lorde’s time in Berlin, called Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992.

“Your silence will not protect you”

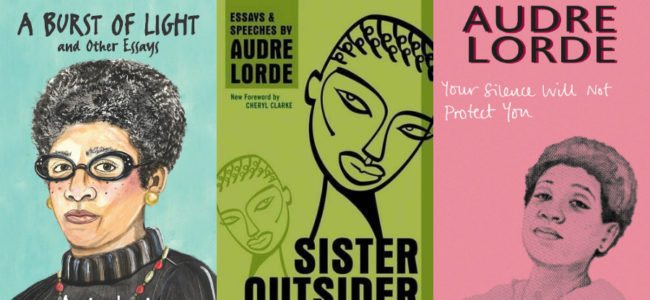

2017’s Your Silence Will Not Protect You by Audre Lorde marked the first time a British publisher brought together Lorde’s essential poetry, speeches and essays in one volume.

However, Lorde’s poetry was published regularly during the 1960s, and it was in 1968 that she published her first volume of poems, The First Cities. Her second volume, the aforementioned Cables to Rage, was published in 1970.

It’s most notable for the poem “Martha,” in which Lorde openly wrote about her homosexuality for the first time.

She published From a Land Where Other People Live in 1973, followed by New York Head Shop and Museum in 1974, though it was 1976’s Coal that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement.

Other works of poetry include Between Our Selves (1976), Hanging Fire (1978), and The Black Unicorn (1978).

Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the ’60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist” – Audre Lorde

She was New York’s poet laureate from 1991 until her death on November 17, 1992.

Lorde was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and had a mastectomy. After her liver cancer diagnosis, she wrote The Cancer Journals (1980). She died of liver cancer at age 58.

In 1982, she released the novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, where she chronicled her life, and the evolution of her sexuality.

In “Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches” (1984), she wrote: “Divide and conquer, in our world, must become define and empower.”

In 1980, Lorde co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press with Barbara Smith and Cherrie Moraga. It was the first US publisher for women of colour.

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”

Founded in 1994, the Audre Lorde Project is a Brooklyn-based organisation for LGBTQ+ people of colour, while the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center is the only primary care centre in New York City to specifically provide medical health care to the city’s LGBTQ+ community.

In 1992, Lorde received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. And, the Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honour works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001.

“I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. And I am not free as long as one person of colour remains chained” – Audre Lorde

How did this story make you feel?