Intimacy co-ordinator behind major queer sex scenes reveals what their job is really like

Intimacy coordinator Robbie Taylor Hunt explains why his job is more than just orchestrating sex scenes. (BBC/Prime Video/Searchlight Pictures/Marc Brenner)

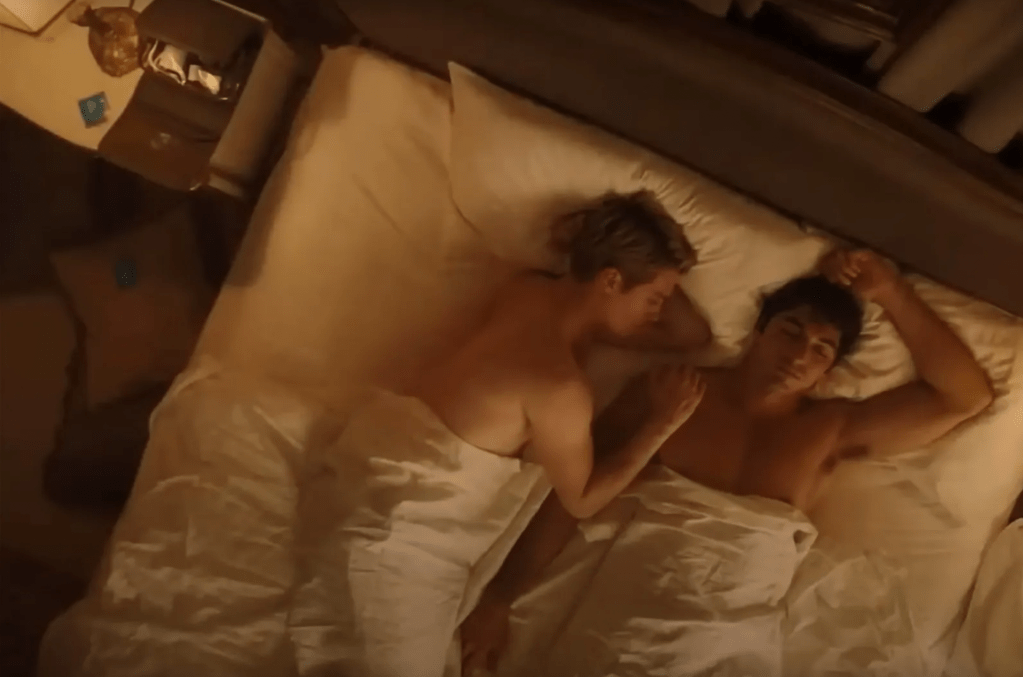

If you’ve seen a stellar gay sex scene on screen or stage recently, there’s a good chance that Robbie Taylor Hunt had something to do with it.

The theatre director began working specifically in intimacy co-ordination in 2019, and has assisted with some of the biggest and best queer productions.

Prime Video’s Red, White & Royal Blue, Sky Atlantic’s Mary & George, and Big Boys, seen on Channel 4, have all had moments of queer pleasure orchestrated by Hunt, while his most recent work can be seen in BBC’s ground-breaking drama Mr Loverman, and on stage in Matthew López’s Reverberation.

However, while intimacy co-ordinators have become more common, their purpose has been blurred by stars such as Toni Collette, Sean Bean and Michael Caine, who have cast doubt on their usefulness.

But, as Hunt explains, being an intimacy co-ordinator is about more than just consent and comfort.

“An intimacy co-ordinator works on intimate content, which means simulated sex, nudity, kissing, physical touch, scenes of bodily functions, childbirth, medical themes, familial intimacy, all sorts of things,” Hunt says. It’s far from being all about sex: “intimate” scenes can include urination, defecation and menstruation.

Consent is one element of his work, making sure that people are working within their boundaries, but there is also a “creative element” to the role. It includes “helping actors, director, director of photography [and] everyone involved, to make sure it is creatively achieving what we need it to for the story, for the characters and for the script”, Hunt adds.

If an intimate scene needs to be more sensual, graphic, realistic, or more uncomfortable, for example, it’s Hunt’s job to make sure that translates on to the screen. Or, indeed, off-screen.

While most entertainment fans think of intimacy co-ordinators as working with filmed sex scenes, their work also extends to the theatre, and that is often a much bigger, more complex job. “It’s an entirely different process,” Hunt points out.

He’s spent the past few months working with Olivier-Award-winner López on Reverberation. The play follows Jonathan, a man struck down by homophobic tragedy, who relies on sex with men he meets online for a sense of self. His life is changed by Claire, an enigmatic woman who moves in to the flat above his, bringing connection to their solitary lives.

“We have time before we rehearse for me to chat to the actors individually and say: ‘This is what’s in the script, what are we thinking about it? What do we want, and not want, to do?’” Hunt explains.

He will speak to the director before the intimacy is choreographed and rehearsed. There are weeks to play with, where Hunt can continue to hone the scenes through tech and dress rehearsals.

“I’m there for the previews as we start to have it in front of an audience,” he says, with that live audience and their comfort being another element for him to consider. “Then… you leave them to it, which feels very strange.”

In TV and film, on the other hand, the rehearsal may happen just a few hours before an intimate scene is shot. Then intimacy co-ordinator is gone.

On Reverberation and his other projects, Hunt has created “a space and comfort… for people to discuss [intimacy] and work on it together,” but he acknowledges some actors, such as Time star Bean, think intimacy co-ordinators “spoil the spontaneity” of sex scenes.

“Different intimacy co-ordinators have different practices where there is a sense of coming in and [saying], ‘I run the shop now’, which, for some processes, is right,” he says.

“I was on set a bit more in my early years, doing things which felt a bit limiting but as time has gone on. As things generally feel a bit better and more supportive around intimacy, and people understand I’m not there to just shut things down, I do actually want to collaborate, [the director] will use me more.

“Of course, sometimes intimacy co-ordinators do need to come in [where] there is a harmful dynamic onset and you do have to put in a few more stop-gaps, or push things a little bit harder to make sure that the baseline of safety is there.”

If one person feels uncomfortable being involved in certain scenes, that can’t always be shared with the rest of the cast and crew. “People can handle different things,” Hunt says.

Those people who feel intimacy co-ordination is a hindrance maybe aren’t seeing the full picture. “There’s a level of confidentiality to it… one person doesn’t feel they need an intimacy co-ordinator, someone else might.”

Considering intimate queer sex scenes in TV and film have been few and far between until recent years, Hunt’s job also entails making sure depictions don’t fall into tired stereotypes. His “pet peeves” are shows that aren’t realistic in terms of the mechanics of LGBTQ+ sex, from the viable positions to how long preparation can take.

“Even with Red, White & Royal Blue, there was some things that went around, people being like: ‘I didn’t even know men could have sex face-to-face’, just because often representations of sex between men are sex from behind,” he says. “That’s a little trope that just perpetuates. You see [that] on screen and people just keep doing that because it’s what we’ve seen on screen.”

There have been other instances where queer stereotypes have led to “gendered ideas”, with muscular and masculine men portrayed as tops, and feminine, more-emotional men seen as bottoms. Hunt’s role is to ask “actually, what makes sense to these characters?”

More than anything, Hunt is honoured to play such a vital role in bringing nuanced, explicit LGBTQ+ stories to stage and screen.

“We went through a phase of being so happy to get queer characters on screen at all, but usually [they were] pretty stereotypical or didn’t have an intimate story because that was seen as ‘a bit much’,” he recalls. “Now it feels like we’re getting authentic, true, fully realised queer stories.”

After all, gay sex portrayals aren’t just about bringing representation for the community. They are an important tool in bringing brilliant entertainment for all to see.

“[Characters are] usually in a very vulnerable moment, where they’re away from lots of other people. I think often, in a good sex scene, you see a different side to someone. That is creatively very juicy for an audience. I’m all for a good, well-done sex scene. They do a lot for a story.”

Reverberation is on stage at the Bristol Old Vic until 2 November.

Share your thoughts! Let us know in the comments below, and remember to keep the conversation respectful.

How did this story make you feel?